Access Journal Content

Open access browsing of table of contents and abstract pages. Full text pdfs available for download for subscribers.

Current Issue: Vol. 30 (3)

Check out NENA's latest Monograph:

Monograph 22

2006 NORTHEASTERN NATURALIST 13(1):39–42

Establishment of the Eastern Gray Squirrel (Sciurus carolinensis)

in Nova Scotia, Canada

Howard M. Huynh1,2,3,*, Geoffrey R. Williams1,4, Donald F. McAlpine2, and Richard

W. Thorington, Jr.5

Abstract - Sciurus carolinensis (Eastern Gray Squirrel) is one of the most recognized sciurids

in North America. Since 1930, apparently isolated Nova Scotia sightings of Eastern Gray Squirrel

have been believed to result from captive releases or escapes. However, the species was

not believed to have become established in the province. Here we report first evidence that the

Eastern Gray Squirrel is now present as a breeding mammal in Nova Scotia.

Sciurus carolinensis Gmelin (Eastern Gray Squirrel) is a common and well-studied

arboreal sciurid in North America (Thorington and Ferrell 2006). Geographically,

Eastern Gray Squirrels are native to the eastern and midwestern United States and

southeastern Canada. The species distribution reaches its northern extent in Canada,

occurring in southeastern Manitoba, western Ontario, southeastern Ontario, southern

Quebec, and southern New Brunswick (Flyger 1999, Hall 1981). Although Eastern

Notes of the Northeastern Nat u ral ist, Issue 17/4, 2010

673

1Department of Biology, Acadia University, Wolfville, NS, Canada B4P 2R6. 2Department of

Natural Science, New Brunswick Museum, Saint John, NB, Canada E2K 1E5. 3Current address

- Department of Biological Sciences, Texas Tech University, Lubbock, TX 79409. 4Department

of Biology, Dalhousie University, Halifax, NS, Canada B3H 4J1. 5Division of Mammals,

Smithsonian Institution National Museum of Natural History. Washington, DC 20013-7012.

*Corresponding author - huynh.hm@rogers.com.

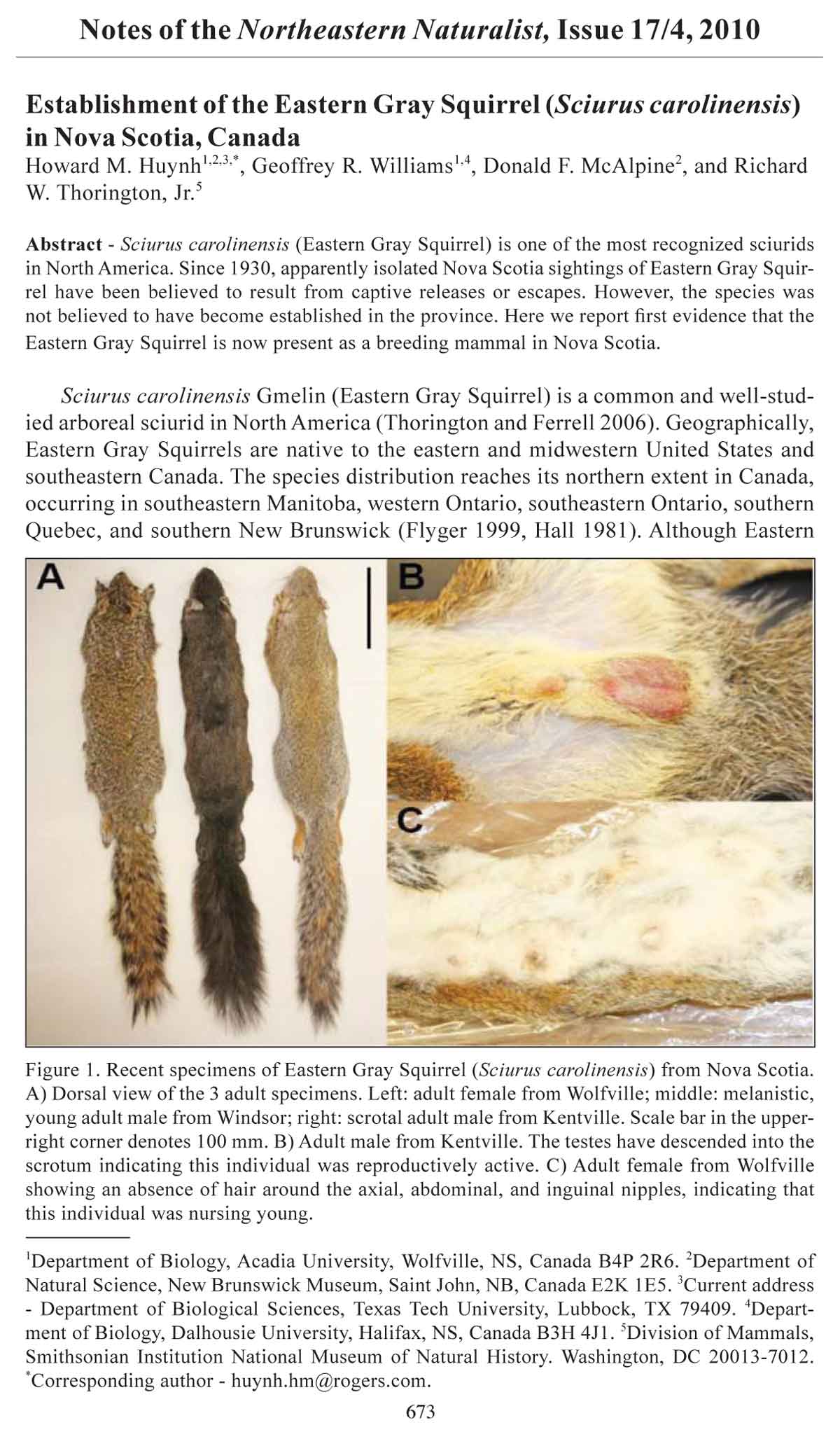

Figure 1. Recent specimens of Eastern Gray Squirrel (Sciurus carolinensis) from Nova Scotia.

A) Dorsal view of the 3 adult specimens. Left: adult female from Wolfville; middle: melanistic,

young adult male from Windsor; right: scrotal adult male from Kentville. Scale bar in the upperright

corner denotes 100 mm. B) Adult male from Kentville. The testes have descended into the

scrotum indicating this individual was reproductively active. C) Adult female from Wolfville

showing an absence of hair around the axial, abdominal, and inguinal nipples, indicating that

this individual was nursing young.

674 Northeastern Naturalist Notes Vol. 17, No. 4

Gray Squirrels have been reported in Nova Scotia with increasing frequency since

1930, these observations are generally believed to represent isolated introductions by

humans (Anderson 1946, Banfield 1974, Rand 1933, Smith 1940). Scott and Hebda

(2004) stated that the species was not established in Nova Scotia. Here we report

evidence that the Eastern Gray Squirrel is now present as a breeding mammal in the

Annapolis Valley region of the province.

Eastern Gray Squirrel sighting reports were brought to our attention, following

which trapping permits were acquired from Nova Scotia Department of Natural Resources

(NSDNR). Two Tomahawk live traps measuring 49.0 cm x 15.5 cm x 15.0

cm were deployed from 16 September to 1 October 2009 on a private property in

Kentville, NS, Canada (45°4'17"N, 64°29'24"W) where there had been reports of

Eastern Gray Squirrels foraging on the 3-acre premises. Trees on the property were

Populus balsamifera L. (Balsam Poplar) and Quercus rubra L. (Northern Red Oak).

The traps were set on a large, 2-tiered wooden bird feeder, and baited with peanut

butter and sunflower seeds. Trapping protocol followed guidelines set by the Animal

Care Committee of the American Society of Mammalogists (Gannon et al. 2007), and

was approved by the Canadian Council on Animal Care.

One adult male Eastern Gray Squirrel was trapped in Kentville on 1 October

2009 and was euthanized with isoflurane (Fig. 1A). A second specimen, a young adult

and melanistic (black morph) male, was live trapped in Windsor, NS (44°59'25"N,

64°7'52"W) on 1 October 2009, independent of our trapping efforts. This squirrel

was relinquished to NSDNR in Kentville, and was also euthanized with isoflurane

(Fig. 1A). In addition, an adult female, killed by a car in Wolfville, NS (45°5'33"N,

64°20'51"W) on 3 May 2007, and subsequently frozen at the Acadia Wildlife Museum,

was made available to us for examination (Fig. 1A). Standard measurements

were taken on all 3 specimens; they were necropsied, and have been deposited in the

mammal collections of the New Brunswick Museum (NBM), Nova Scotia Museum

of Natural History (NSMNH), and Acadia Wildlife Museum (AWM), and represent

the first voucher specimens for the species for Nova Scotia.

Morphometric and reproductive data for the 3 Nova Scotia Eastern Gray Squirrel

specimens are presented in Table 1. Necropsy revealed that 2 of the specimens were

reproductively active: a scrotal adult male with testes 15.2 mm x 8.2 mm (Fig. 1B),

and a lactating adult female. The absence of hair around the axial, abdominal, and

inguinal nipples of the female indicates that this latter specimen was recently nursing

young (Fig. 1C); internal examination revealed 4 placental scars, 2 in each of

the left and right uterine horns. The melanistic, young adult male from Windsor had

non-scrotal testes measuring 12.8 mm x 5.2 mm. Melanism, although the dominant

Table 1. Morphometric and necropsy data for 3 specimens of Eastern Gray Squirrel (Sciurus

carolinensis) collected from Nova Scotia, Canada. External measurements (recorded in mm):

TL = total body length, including tail; TV = length of tail, base to tip; HF = length of hind foot;

E = length of ear, notch to tip; mass was recorded in grams.

External measurements

Catalogue # Sex Date collected Locality TL TV HF E Mass

AWM MA Male, adult; 1 October 2009 Kentville, 490.0 224.0 64.0 33.0 540.0

3022 scrotal Kings County

NSMNH Male, adult; 1 October 2009 Windsor, 495.0 220.0 64.0 31.0 524.2

78039 non scrotal Hants County

NBM Female, adult; 3 May 2007 Wolfville, 488.0 219.0 60.0 28.0 626.0

11562 lactating Kings County

2010 Northeastern Naturalist Notes 675

color morph in some northern populations of Eastern Gray Squirrel (Woods 1980),

has been infrequently reported in Nova Scotia (A. Hebda, NSMNH, Halifax, NS,

Canada, pers. comm.) and adjacent New Brunswick (Morris 1948).

Although Gilpin (1869) noted receipt of an Eastern Gray Squirrel skin from

Nova Scotia, Rand (1933) was the first to suggest that any sightings of the species

were probably escaped cage animals brought to the province by tourists. The statement

of Rand (1933) has since provided the basis for various conflicting accounts

of the species status in Nova Scotia. Smith (1940) noted that the species did not occur

regularly on the mainland of Nova Scotia and that its status was still unsettled;

he acknowledged receiving several reports of the species, but felt that these were

possibly caged animals that had escaped. Anderson (1946) noted the species was occasionally

reported from various parts of Nova Scotia, but attributed their presence

to escaped cage animals. Peterson (1966) mapped the species as present across much

of mainland Nova Scotia, and suggested that the Eastern Gray Squirrel was established

by introduction in the province. (Interestingly, none of the aforementioned

authors appeared to have been aware of a report from the Halifax Evening Express,

dated 17 June 1864, that stated: “ … a small colony of gray squirrels presented to

the Province by Mr. Thomas Leahy, who brought them up from Philadelphia. These

were placed in a tree near the Province building ... to be released in the wild within

a fortnight to 3 weeks." [A. Hebda, pers. comm.]) Banfield (1974) similarly mapped

the species for the province and commented “escaped pets occasionally seen in Nova

Scotia.” More recently, Scott and Hebda (2004) report that the Eastern Gray Squirrel

has been repeatedly introduced into Nova Scotia during the 20th Century, most often

in urban areas (e.g., sightings reported from Amherst and Halifax; additional sightings

reported in the Annapolis Valley during the last several years include Wolfville,

Kentville, Berwick, Middleton, and Kingston; J. Wolford, Blomidon Naturalist Society,

Wolfville, NS, Canada, pers. comm.), but also stated that the species has never

become established in the province.

It is possible that the presence of Eastern Gray Squirrels in Nova Scotia may

represent a natural range extension for the species from New Brunswick. Eastern

Gray Squirrels are known to travel relatively long distances (Koprowski 1994); dispersal

rates are particularly high during the autumn, when individuals are in search

of new territory (known as the fall reshuffle; Flyger 1999). The Chignecto Isthmus

is a relatively narrow (24-km wide) land bridge that connects Nova Scotia to New

Brunswick and the rest of mainland Canada, and functions as a wildlife corridor

for several species of mammals (MacKinnon and Kennedy 2008, Scott and Hebda

2004), facilitating the movement of individuals, and possibly gene flow, from New

Brunswick to Nova Scotia. To our knowledge, no sightings of Eastern Gray Squirrels

have been reported around regions and townships in the Chignecto Isthmus, but

they may occur in these areas, considering their ability to adapt to a wide variety of

natural and human-modified environments (Banfield 1974, Flyger 1999). Given accounts

of repeated past introductions of Eastern Gray Squirrels into Nova Scotia, it

is possible that the establishment of this species in Nova Scotia is a combination of

high propagule pressure (Lockwood et al. 2009) created by human sponsorship and

(reinforced by) natural population expansion from New Brunswick.

In summary, we suggest that the 3 specimens reported on above, combined

with numerous and concurrent verified sightings of Eastern Gray Squirrels in the

province, support our belief that the Eastern Gray Squirrel has now established a

breeding population in Nova Scotia (cf. Scott and Hebda 2004). This increases the

total number of sciurids known to occur in Nova Scotia from 5 to 6—i.e., S. caro676

Northeastern Naturalist Notes Vol. 17, No. 4

linensis (Eastern Gray Squirrel), Tamiasciurus hudsonicus Exleben (American Red

Squirrel), Tamias striatus L. (Eastern Chipmunk), Glaucomys volans L. (Southern

Flying Squirrel), G. sabrinus Shaw (Northern Flying Squirrel), and Marmota monax

L. (Woodchuck) (Scott and Hebda 2004). Eastern Gray Squirrels are known to damage

crops and personal property (Flyger 1999), injure and kill young trees via bark

stripping (Kenward and Parish 1986), prohibit the natural regeneration of hardwood

forests (Pigott et al. 1991), prey on eggs and nestlings of tree-nesting birds (Flyger

1999), and competitively displace and exclude native sciurids and other granivorous

species (Bruemmer et al. 2000, but see Gonzales et al. 2008). Although the future

ecological impact of the Eastern Gray Squirrel in Nova Scotia is unknown, it seems

likely that this highly adaptable species can be expected to expand its range and increase

in abundance in the province in the decades ahead.

Acknowledgements. We thank James Wolford for providing information and records

of Eastern Gray Squirrels in Nova Scotia, and Fred Scott for allowing necropsy

of the specimen deposited in the Acadia Wildlife Museum. Thanks to Allan Bland,

Mark Elderkin, Pamela Mills, and Julie Towers at NSDNR for forwarding the Windsor

specimen to us for examination and for assistance with permits. H.M. Huynh

and G.R. Williams would like to extend their gratitude and appreciation to Ed and

Mary Anne Sulis for permitting trapping on their property in Kentville. H.M. Huynh

would like to thank Brian Wilson for advice and assistance, Andrew Hebda for helpful

discussions and bringing the Halifax Evening Express report to our attention, and

Donald Stewart and the New Brunswick Museum for continued support during his

studies and research at Acadia University. This work was funded in part by the New

Brunswick Museum Florence M. Christie Fellowship in Zoology to H.M. Huynh.

Literature Cited

Anderson, R.M. 1946. Catalogue of Canadian Recent mammals. National Museum of Canada

Bulletin 102:1–238.

Banfield, A.W. 1974. The Mammals of Canada. University of Toronto Press, Toronto, ON,

Canada. 438 pp.

Bruemmer, C., P. Lurz, K. Larsen, and J. Gurnell. 2000. Impacts and management of the alien

Eastern Gray Squirrel in Great Britain and Italy: Lessons for British Columbia. Pp 341–

350, In L.M. Darling (Ed.). Proceedings of the Conference on the Biology and Management

of Species and Habitats at Risk, Kamloops, BC, 15–19 February 1999. BC Ministry

of Environment, Lands and Parks, Victoria, BC and University College of the Cariboo,

Kamloops, BC, Canada. 490 pp.

Flyger, V. 1999. Eastern Gray Squirrel (Sciurus carolinensis). Pp: 451–453, In D.E. Wilson and

S. Ruff (Eds.). The Smithsonian Book of North American Mammals. Smithsonian Institution

Press, Washington, DC. 750 pp.

Gannon, W. L., R.S. Sikes, and the Animal Care and Use Committee (ACUC) of the American

Society of Mammalogists (ASM). 2007. Guidelines of the American Society of Mammalogists

for the use of the wild mammals in research. Journal of Mammalogy 88:809–823.

Gilpin, J.B. 1869. On the mammals of Nova Scotia. Proceeding of the Nova Scotian Institute

of Science 2:58–69.

Gonzales, E.K., Y.F. Wiersma, A.I. Maher, and T.D. Nudds. 2008. Positive relationship between

non-native and native squirrels in an urban landscape. Canadian Journal of Zoology

86:356–363.

Hall, E.R. 1981. The Mammals of North America. 2nd Edition, Volume I. John Wiley and Sons,

Inc., New York, NY. 89 pp.

Kenward, R.E., and T. Parish. 1986. Bark stripping by Grey Squirrels (Sciurus carolinensis).

Journal of Zoology (London) 210:473–481.

Koprowski, J.L. 1994. Sciurus carolinensis. Mammalian Species 480:1–9.

2010 Northeastern Naturalist Notes 677

Lockwood, J.L., P. Cassey, and T.M. Blackburn. 2009. The more you introduce, the more you

get: The role of colonization pressure and propagule pressure in invasion ecology. Diversity

and Distributions 15:904–910.

MacKinnon, C.M., and A.C. Kennedy. 2008. Canada Lynx, Lynx canadensis, use of the

Chignecto Isthmus and the possibility of gene flow between populations in New Brunswick

and Nova Scotia. The Canadian Field-Naturalist 122:166–168.

Morris, R.F. 1948. The land mammals of New Brunswick. Journal of Mammalogy 29:165–176.

Peterson, R.L. 1966. The Mammals of Eastern Canada. Oxford University Press, Toronto, ON,

Canada. 465 pp.

Pigott, C.D., A.C. Newton, and S. Zammit. 1991. Predation of acorns and oak seedlings by Grey

Squirrels. Quarterly Journal of Forestry 85:172–178.

Rand, A.L. 1933. Notes on the mammals of the interior of western Nova Scotia. Canadian

Field-Naturalist 47:41–50.

Scott, F.W., and A.J. Hebda. 2004. Annotated list of the mammals of Nova Scotia. Proceedings

of the Nova Scotia Institute of Science 42:189–208.

Smith, R.W. 1940. The land mammals of Nova Scotia. American Midland Naturalist 24:213–241.

Thorington, R.W., Jr., and K. Ferrell. 2006. Squirrels: The Animal Answer Guide. John Hopkins

University Press, Baltimore, MD. 183 pp.

Woods, S.E. 1980. The Squirrels of Canada. National Museums of Canada, Ottawa, ON,

Canada. 195 pp.

The Northeastern Naturalist is a peer-reviewed journal that covers all aspects of natural history within northeastern North America. We welcome research articles, summary review papers, and observational notes.

The Northeastern Naturalist is a peer-reviewed journal that covers all aspects of natural history within northeastern North America. We welcome research articles, summary review papers, and observational notes.