Access Journal Content

Open access browsing of table of contents and abstract pages. Full text pdfs available for download for subscribers.

Current Issue: Vol. 30 (3)

Check out NENA's latest Monograph:

Monograph 22

2006 NORTHEASTERN NATURALIST 13(1):39–42

Predation of Spotted Turtle (Clemmys guttata) Hatchling by

Green Frog (Rana clamitans)

James D. DeGraaf

1,* and Daniel G. Nein1

Abstract - Predation of Clemmys guttata (Spotted Turtle) hatchlings by Rana clamitans

(Green Frog) has not previously been reported. During Spotted Turtle nesting surveys in urban

Massachusetts, a Spotted Turtle hatchling was radio-tagged and tracked to determine initial

movement patterns. Fifteen days post-tagging, the Spotted Turtle hatchling was located in the

gut of an adult female Green Frog. Given the abundance of Green Frogs in semi-permanent

wetlands, they may be important predators on turtle hatchlings. Further studies are required

to determine the frequency of Green Frog predation on turtle hatchlings and to evaluate total

predation pressure on and survival of Spotted Turtle hatchlings.

Introduction. Chelonian hatchlings are vulnerable to the effects of desiccation

and are preyed on by a variety of animals, including snakes, birds, ants, small mammals,

and frogs (Ernst and Lovich 2009, Finkler 2001). Adult Rana catesbeiana

Shaw (Bullfrog) are aggressive predators and feed on a wide variety of prey including

young turtles (Hunter et al. 1999). Prey of the similarly sized Rana clamitans

Latreille (Green Frog) includes aquatic and terrestrial insects, small fish, molluscs,

and small frogs (DeGraaf and Yamasaki 2001, Hamilton 1948, Hunter et al.

1999, Rappole 2007); however, predation on turtles, specifically Clemmys guttata

Schneider (Spotted Turtle) hatchlings, has not been documented to date.

Methods. Spotted Turtle nesting surveys were conducted in Cohasset, MA, during

the months of May and June, 2002 through 2009. The identification and location

of nests followed thread-bobbin tracking methodology described by Wilson (1994).

On 22 June 2007, a Spotted Turtle nest containing five eggs was located in coarse

soil along a driveway 2 m from the edge of water in a semi-permanent wetland. On

13 September 2007, four hatchlings successfully emerged from the nest. One egg was

fertilized, but did not hatch for unknown reasons. As part of a preliminary evaluation

to track initial Spotted Turtle hatchling movements, one hatchling was tagged with

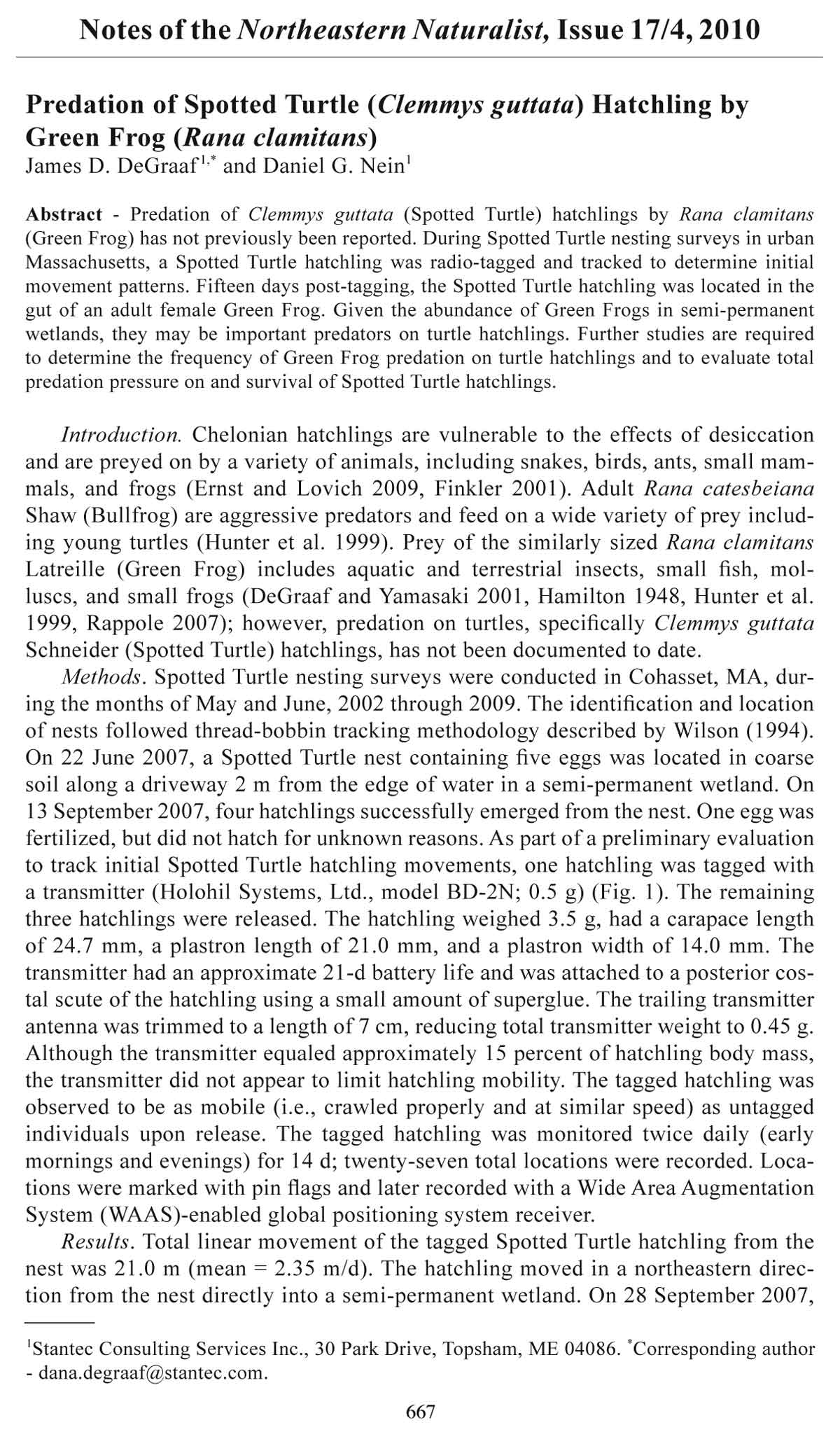

a transmitter (Holohil Systems, Ltd., model BD-2N; 0.5 g) (Fig. 1). The remaining

three hatchlings were released. The hatchling weighed 3.5 g, had a carapace length

of 24.7 mm, a plastron length of 21.0 mm, and a plastron width of 14.0 mm. The

transmitter had an approximate 21-d battery life and was attached to a posterior costal

scute of the hatchling using a small amount of superglue. The trailing transmitter

antenna was trimmed to a length of 7 cm, reducing total transmitter weight to 0.45 g.

Although the transmitter equaled approximately 15 percent of hatchling body mass,

the transmitter did not appear to limit hatchling mobility. The tagged hatchling was

observed to be as mobile (i.e., crawled properly and at similar speed) as untagged

individuals upon release. The tagged hatchling was monitored twice daily (early

mornings and evenings) for 14 d; twenty-seven total locations were recorded. Locations

were marked with pin flags and later recorded with a Wide Area Augmentation

System (WAAS)-enabled global positioning system receiver.

Results. Total linear movement of the tagged Spotted Turtle hatchling from the

nest was 21.0 m (mean = 2.35 m/d). The hatchling moved in a northeastern direction

from the nest directly into a semi-permanent wetland. On 28 September 2007,

Notes of the Northeastern Nat u ral ist, Issue 17/4, 2010

667

1Stantec Consulting Services Inc., 30 Park Drive, Topsham, ME 04086. *Corresponding author

- dana.degraaf@stantec.com.

668 Northeastern Naturalist Notes Vol. 17, No. 4

Figure 1. A Clemmys guttata (Spotted Turtle) hatchling was tagged with a radio transmitter

(Holohil Systems, Ltd., model BD-2N; 0.5 g) on 13 September 2007 in Cohasset, MA. The

transmitter was attached to the posterior costal scute using superglue. Photograph © Daniel

Nein, Stantec Consulting Services Inc.

2010 Northeastern Naturalist Notes 669

rapid transmitter movement was detected during early morning telemetry surveys.

The transmitter signal was confirmed to come from an adult female Green Frog

(100.0 mm snout–vent length [SVL]) which was captured in the water adjacent to

the former Spotted Turtle nest. The Green Frog, identified through observation of a

prominent dorso-lateral ridge (Hunter et al. 1999, Rappole 2007), was euthanized

(i.e., double pithed) and quickly dissected. The slightly digested hatchling was

found along with vegetation in the gut of the Green Frog with the transmitter still

attached. Based on tracking frequency and condition of the hatchling, the hatchling

was likely subjected to digestive processes for ≤24 h.

Discussion. To our knowledge, this is the first confirmed documentation of Green

Frog predation on Spotted Turtle hatchlings. Our data indicates that adult Green Frog

and Bullfrog diets may overlap more than previously described (Werner et al. 1995)

and provides further insight into predation pressure on Spotted Turtle hatchlings.

Bullfrog and Green Frog distributions overlap; however, Bullfrogs are highly

aquatic and distribution is skewed to larger permanent water bodies; Green Frogs inhabit

shallow permanent and semi-permanent freshwater habitats and are often found

on land and close to water (DeGraaf and Yamasaki 2001, Hunter et al. 1999, Werner

et al. 1995). Green Frogs and Spotted Turtles inhabit small shallow-water bodies,

including isolated vernal pools in Massachusetts (Ernst and Lovich 2009, Milam and

Melvin 2001). Our study area contained semi-permanent wetland habitats in an urban

area. Green Frogs may persist in small semi-permanent wetlands where Bullfrogs

cannot, and therefore may be an important predator of Spotted Turtles in these areas.

Green Frog diets reflect habitat use and can vary between sites (Hunter et al. 1999). In

our study area, Green Frog diet may shift more to terrestrial prey as semi-permanent

wetlands experience seasonal drying during summer and early fall months. The

maximum size range for Green Frogs is 90–100 mm SVL (Rappole 2007, Werner et

al. 1995). The female Green Frog that depredated the Spotted Turtle hatchling in our

study was large and at the size limit of this species. Large adult Green Frogs may

forage on larger prey as evidenced by this observation. Further studies are required to

determine the frequency of Green Frog predation on turtle hatchlings and to evaluate

total predation pressure and survival of Spotted Turtle hatchlings.

Acknowledgments. We thank Steve C. Soldan for assistance with field work, Jessica

Griffin, Richard M. DeGraaf, and Steven K. Pelletier for their reviews, and two

anonymous reviewers for their thoughtful comments. Collection, handling, and tagging

procedures followed Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife Scientific

Collection Permit conditions and accepted tagging methods. The Massachusetts Bay

Transportation Authority provided funding for this study.

Literature Cited

DeGraaf, R.M., and M. Yamasaki. 2001. New England Wildlife, Habitat, Natural History, and

Distribution. University Press of New England, Hanover, NH. 482 pp.

Ernst, C.H., and J.E. Jovich. 2009. Turtles of the United States and Canada. Second Edition.

The Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, MD. 827 pp.

Finkler, M.S. 2001. Rates of water loss and estimates of survival time under varying humidity

in juvenile Snapping Turtles (Chelydra serpentina). Copeia 2:521–525.

Hamilton, W.J. 1948. The food and feeding behavior of the Green Frog, Rana clamitans (Latreille),

in New York State. Copeia 1948:203–207.

Hunter, M.L., A. Calhoun, and M. McCullough (Eds.). 1999. Maine Amphibians and Reptiles.

University of Maine Press, Orono, ME. 272 pp.

Milam, J.C., and S.M. Melvin. 2001. Density, habitat use, and conservation of Spotted Turtles

(Clemmys guttata) in Massachusetts. Journal of Herpetology 35:418–427.

670 Northeastern Naturalist Notes Vol. 17, No. 4

Rappole, J.H. 2007. Wildlife of the Mid-Atlantic: A Complete Reference Manual. University of

Pennsylvania Press, Philadelphia, PA. 372 pp.

Werner, E.E., G.A. Wellborn, and M.A. McPeek. 1995. Diet composition in postmetamorphic

Bullfrogs and Green Frogs: Implications for interspecific predation and competition. Journal

of Herpetology 29:600–607.

Wilson, D.S. 1994. Tracking small animals with thread bobbins. Herpetological Review

25:13–14.

The Northeastern Naturalist is a peer-reviewed journal that covers all aspects of natural history within northeastern North America. We welcome research articles, summary review papers, and observational notes.

The Northeastern Naturalist is a peer-reviewed journal that covers all aspects of natural history within northeastern North America. We welcome research articles, summary review papers, and observational notes.