2009 SOUTHEASTERN NATURALIST 8(2):355–362

Myotis septentrionalis Trouessart (Northern Long-eared

Bat) Records from the Coastal Plain of North Carolina

Adam D. Morris1, Maarten J. Vonhof2, Darren A. Miller3,

and Matina C. Kalcounis-Rueppell1,*

Abstract - Myotis septentrionalis (Northern Long-eared Bat) is a small, insectivorous

bat found in the eastern United States and Canada. Along the east coast, its range

is thought to extend as far south as the Great Dismal Swamp in coastal Virginia. We

captured six M. septentrionalis in the northern coastal plain region of North Carolina.

Field identification was based on characters of ear and tragus length and confirmed

with mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit I sequences. These captures signify

the presence of a resident population of M. septentrionalis in the northern coastal

plain of North Carolina. Future work is needed to document range limits and hibernation

behavior of this species in the piedmont and coastal plain of North Carolina.

Introduction

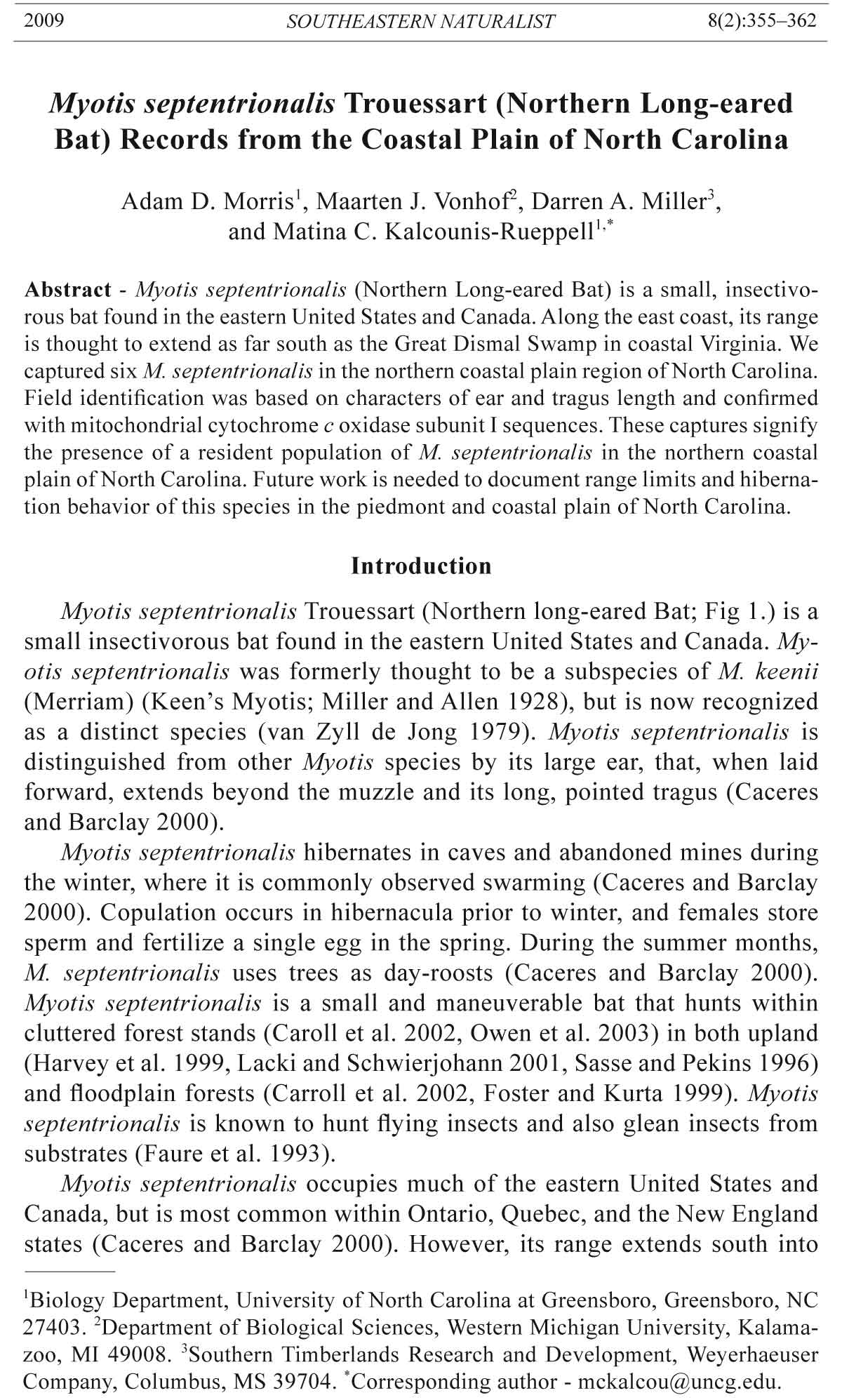

Myotis septentrionalis Trouessart (Northern long-eared Bat; Fig 1.) is a

small insectivorous bat found in the eastern United States and Canada. Myotis

septentrionalis was formerly thought to be a subspecies of M. keenii

(Merriam) (Keen’s Myotis; Miller and Allen 1928), but is now recognized

as a distinct species (van Zyll de Jong 1979). Myotis septentrionalis is

distinguished from other Myotis species by its large ear, that, when laid

forward, extends beyond the muzzle and its long, pointed tragus (Caceres

and Barclay 2000).

Myotis septentrionalis hibernates in caves and abandoned mines during

the winter, where it is commonly observed swarming (Caceres and Barclay

2000). Copulation occurs in hibernacula prior to winter, and females store

sperm and fertilize a single egg in the spring. During the summer months,

M. septentrionalis uses trees as day-roosts (Caceres and Barclay 2000).

Myotis septentrionalis is a small and maneuverable bat that hunts within

cluttered forest stands (Caroll et al. 2002, Owen et al. 2003) in both upland

(Harvey et al. 1999, Lacki and Schwierjohann 2001, Sasse and Pekins 1996)

and fl oodplain forests (Carroll et al. 2002, Foster and Kurta 1999). Myotis

septentrionalis is known to hunt fl ying insects and also glean insects from

substrates (Faure et al. 1993).

Myotis septentrionalis occupies much of the eastern United States and

Canada, but is most common within Ontario, Quebec, and the New England

states (Caceres and Barclay 2000). However, its range extends south into

1Biology Department, University of North Carolina at Greensboro, Greensboro, NC

27403. 2Department of Biological Sciences, Western Michigan University, Kalamazoo,

MI 49008. 3Southern Timberlands Research and Development, Weyerhaeuser

Company, Columbus, MS 39704. *Corresponding author - mckalcou@uncg.edu.

356 Southeastern Naturalist Vol.8, No. 2

Alabama and Georgia, and west into Alberta, British Columbia, Montana,

and Wyoming (Caceres and Barclay 2000), and the species can be locally

common in these regions. Along the east coast, the range is thought to extend

as far south as the Great Dismal Swamp in coastal Virginia (specimens:

AMNH 93177 and USNM 23277, see Appendix 1 for full names; Webster

et al. 1985). Previous distribution maps suggesting a presence in the North

Carolina coastal plain (Caceres and Barclay 2000) are drawn broadly and

are based on few actual records. Although the Great Dismal Swamp extends

into North Carolina, recent surveys have found no evidence of M. septentrionalis

in the coastal plain of North Carolina (Clark 1999, Lambiase et al.

2002, McDonnell 2001). Records of M. septentrionalis in North Carolina

are mainly from the western portion of the state, with the exception of one

isolated record in the piedmont (NCSM 45; Fig. 2) and one reportedly in the

southern coastal plain (David Webster, University of North Carolina, Wilmington,

NC, pers. comm.; Fig. 2).

Methods

During the summer of 2007, we captured bats using mist-nets at the Tidewater

Research Station, located in the coastal plain 5 miles east of Plymouth

in Washington County, NC. We captured six M. septentrionalis in mist-nets

set along a closed-canopy, overgrown road corridor directly adjacent to a

natural forested wetland area surrounded by intensively managed Pinus taeda

L. (Loblolly Pine). Field identification to species included measurements

Figure 1. Individual juvenile female M. septentrionalis (ID ADM35 from Table 1)

captured in the northern coastal plain of North Carolina during summer 2007.

2009 A.D. Morris, M.J. Vonhof, D.A. Miller, and M.C. Kalcounis-Rueppell 357

and characters of ear and tragus length (Table 1; Fig 1). We also collected

tissue samples from wing membranes, and all bats were released at site of

capture. We did not mark captured bats in any way. However, because we

collected a wing biopsy, we could tell if individuals were recaptures based

on either the presence of the biopsy site or scaring over the biopsy site.

Capture and handling protocols were approved by the UNCG Institutional

Figure 2. Map showing the range of M. septentrionalis in North Carolina, South

Carolina, Virginia, and Maryland. Shaded counties contain documented records of M.

septentrionalis; the filled black circle represents our capture site. Map was generated

using a map layer compiled by Bat Conservation International (available at http://

nationalatlas.gov/mld/bat000m.html) and a compilation of local records (D. Webster,

pers. comm.).

Table 1. Measurements of the six individuals of M. septentrionalis captured in the northern

coastal plain of North Carolina during summer, 2007. Measurements of length were taken with

standard metric calipers and measurements of mass taken with a Pesola® spring scale.

Forearm Ear Weight

ID Date Time Sex Age (mm) (mm) (g)

ADM31 6/11/2007 10:15 PM Male Adult 33 n/a 4.95

ADM34 6/18/2007 9:38 PM Female Juvenile 34 16 4.95

ADM35 6/18/2007 11:40 PM Female Juvenile 34 16 5.45

ADM36 6/25/2007 9:50 PM Female Juvenile 36 n/a 5.95

ADM41 6/25/2007 2:15 AM Male Juvenile 36 15 5.50

ADM50 7/2/2007 10:05 PM Female Juvenile 35 n/a 5.45

358 Southeastern Naturalist Vol.8, No. 2

Animal Care and Use Committee (# 06-11) and complied with recommendations

of the American Society of Mammalogists.

To confirm species identification, we compared mitochondrial cytochrome

c oxidase subunit I (COI) sequences from these six bats to those of

M. septentrionalis collected elsewhere and to other eastern North American

bats in the genus Myotis that are also found in North Carolina (Fig. 3, Appendix

2). We obtained partial COI sequences (bidirectionally sequenced)

using primers and cycling conditions outlined in Hebert et al. (2003), and

cleaned and aligned sequences using CodonCode Aligner 2.04 (CodonCode

Corporation, Dedham, MA), resulting in a final fragment length of 636 bp.

We estimated sequence divergences by using the Kimura-2-Parameter distance

model and graphically displayed these in a neighbor-joining tree using

PAUP (v. 4.0b10; Swofford 2002).

Figure 3. Neighbor-joining phylogram of COI sequences based on Kimura 2-parameter

distances, showing the specimens from Washington County, NC (two unique

haplotypes among the six specimens, labeled ADM31 and ADM50) grouping with

other M. septentrionalis samples from other parts of the range. Details of specimens

included can be found in Appendix 2.

2009 A.D. Morris, M.J. Vonhof, D.A. Miller, and M.C. Kalcounis-Rueppell 359

Results and Discussion

Five of the six bats captured in North Carolina shared identical

haplotypes (ADM31 through ADM41; see Table 1, Figure 3). Four M.

septentrionalis specimens (CM82047, CS04, JJ43, UAM68932) from various

locations shared the same haplotype (Fig. 3). The two M. austroriparius

specimens (FBF11 and AM168) shared the same haplotype (Fig. 3). Mean

sequence divergence between the two unique haplotypes observed in North

Carolina and other M. septentrionalis specimens (4 unique haplotypes) was

0.4%, while sequence divergence with other eastern North American Myotis

averaged 9.7% (ranging from 8.5% with M. lucifugus to 13.8% with M. austroriparius).

The two haplotypes from North Carolina clearly grouped with

other M. septentrionalis in the neighbor-joining analysis (Fig. 3), confirming

identification of the six bats.

The six bats we captured represent both adult and juveniles (young of the

year in 2007), suggesting reproduction of these bats in this area. These six

bats were captured mid-breeding season (11 June through 2 July) on 4 different

nights at the same mist-net site, suggesting that these were not migrating

individuals. Thus, based on seasonal timing of adult and juveniles captured

over multiple nights, we suggest that these M. septentrionalis signify a

resident population of this species in the northern coastal plain of North

Carolina as opposed to stray captures.

This population is 96 km further south of the Great Dismal Swamp localities

in Virginia. The area where these bats were captured refl ects habitat

preferences of this species in other parts of its range (Carroll et al. 2002,

Harvey et al. 1999, Owen et al. 2003). That is, these bats were captured in a

mist-net strung across an overgrown roadway adjacent to mature forest stands.

However, our captures were not in close proximity to cave hibernacula. Myotis

septentrionalis are thought remain close to hibernacula during summer foraging

(Caceres and Barclay 2000). Since no caves exist in the coastal plain of

North Carolina, our captures imply that these bats either 1) travel much further

to hibernacula than previously thought; 2) utilize alternative hibernacula, such

as tree cavities; or 3) do not hibernate during the mild winters in this area. In

the coastal plain, M. septentrionalis may hibernate in tree cavities or buildings,

like Corynorhinus rafinesquii (Lesson) (Rafinesque’s Big-eared Bat)

(Trousdale and Beckett 2005, Trousdale et al. 2008).

Future work is needed to document range limits of this species and to

fill in gaps between the location in our study and known locations of the

species to the north and west. Future studies should also examine hibernation

behaviors of M. septentrionalis in the piedmont and coastal plain of

North Carolina.

Acknowledgments

Funding was provided by Weyerhaeuser Company, the University of North Carolina

at Greensboro, and Western Michigan University. J. Hart-Smith and D. Allgood

assisted with fieldwork. Discussions with D. Webster, M. Clark, and L. Gatens were

360 Southeastern Naturalist Vol.8, No. 2

appreciated. We thank the curators and institutions for their loans of specimens and

tissues: L.K. Ammerman with the Angelo State Natural History Collection, S.B.

McLaren with the Carnegie Museum of Natural History, and L. Olson with the University

of Alaska Museum. We are also indebted to the researchers who provided

wing-membrane samples, including R. Benedict, E. Britzke, M. Clark, R. Currie, E.

Gates, J. Johnson, A. Miles, and C. Stihler.

Literature Cited

Caceres, M.C., and R.M.R. Barclay. 2000. Myotis septentrionalis. Mammalian Species

No. 634:1–4.

Carroll, S.K., T.C. Carter, and G.A. Feldhammer. 2002. Placements of nets for bats:

Effects on perceived fauna. Southeastern Naturalist 1:193–198.

Clark, M.K. 1999. Results of a bat survey in the lower Roanoke River Basin. Report

prepared for the North Carolina Natural Heritage Trust Fund, North Carolina

Natural Heritage Program, Raleigh, NC. 36 pp.

Faure, P.A., J.H. Fullard, and J.W. Dawson. 1993. The gleaning attacks of the Northern

Long-eared Bat, Myotis septentrionalis, are relatively inaudible to moths.

Journal of Experimental Biology 178:173–189.

Foster, R.W., and A. Kurta. 1999. Roosting ecology of the Northern Bat (Myotis septentrionalis)

and comparisons with the endangered Indiana Bat (Myotis sodalis).

Journal of Mammalogy 80:659–672.

Harvey, M.J., J.S Altenbach, and T.L. Best. 1999. Myotis septentrionalis. Pp. 45, In

Bats of the United States. Arkansas Game and Fish Commission, Little Rock,

AR. 64 pp.

Hebert, P.D.N., A. Cywinska, S.L. Ball, and J.R. deWaard. 2003. Biological identifications through DNA barcodes. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B

270:313–321.

Lacki, M.J., and J.H. Schwierjohann. 2001. Day-roost characteristics of Northern

Bats in mixed mesophytic forest. Journal of Wildlife Management 65:482–488.

Lambiase, S.J., M.K.Clark, and L.J. Gatens. 2002. Bat (Chiroptera) Survey of North

Carolina State Parks 1999–2001. North Carolina Division of Parks and Recreation

and North Carolina State Museum of Natural Sciences, Raleigh, NC.

McDonnell, J.M. 2001. Use of bridges as day roosts by bats in the North Carolina

coastal plain. M.Sc. Thesis. North Carolina State University, Raleigh, NC. 74 pp.

Miller, G.S., Jr., and G.M. Allen. 1928. The American bats of the genera Myotis and

Pizonyx. Bulletin of the United States National Museum 144:1–218.

Owen, S.F., M.A. Menzel, W.M. Ford, B.R. Chapman, K.V. Miller, J.W. Edwards,

and P.B. Wood. 2003. Home-range size and habitat used by the Northern Myotis

(Myotis septentrionalis). American Midland Naturalist 150:352–359.

Sasse, D.B., and P.J. Pekins. 1996. Summer roosting ecology of Northern Long-eared

Bats (Myotis septentrionalis) in the White Mountain National Forest. PP. 91–101,

In R.M.R. Barclay and R.M. Brigham (Eds.). Bats and Forests Symposium. British

Columbia Ministry of Forests, Victoria, BC, Canada.

Swofford, D.L. 2002. PAUP*: Phylogenetic analysis using parsimony (*and other

methods), 4.0 Beta. Sinauer Associates, Sunderland, MA.

Trousdale A.W., D.C. Beckett. 2005. Characteristics of tree roosts of Rafinesque’s

Big-eared Bat (Corynorhinus rafinesquii) in southeastern Mississippi. American

Midland Naturalist 154:442–449.

2009 A.D. Morris, M.J. Vonhof, D.A. Miller, and M.C. Kalcounis-Rueppell 361

Trousdale A.W., D.C. Beckett and S.L. Hammond. 2008. Short-term roost fidelity

of Rafinesque’s Big-eared Bat (Corynorhinus rafinesquii) varies with habitat.

Journal of Mammalogy 89:477–484.

van Zyll de Jong, C.G. 1979. Distribution and systematic relationships of Long-eared

Myotis in western Canada. Canadian Journal of Zoology 57:987–994.

Webster, D.W., J.F. Parnell, and W.C. Biggs, Jr. 1985. Mammals of the Carolinas,

Virginia, and Maryland, University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill, NC.

255 pp.

362 Southeastern Naturalist Vol.8, No. 2

Appendix 1. Full names of museum acronyms for specimens listed in text and not

used in the genetic analysis.

AMNH = American Museum of Natural History.

NCSM = North Carolina State Museum of Natural Sciences.

USNM = National Museum of Natural History.

Appendix 2. Locations of specimens used in the genetic analyses. Voucher specimens

used in this study were housed in the Carnegie Museum of Natural History,

Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania (CM), the Angelo State Natural History Collection, San

Angelo, TX (ASK), and the University of Alaska Museum, Fairbanks, AK (UAM).

Additional wing membrane samples were used, and housed at Western Michigan

University (all other abbreviations).

Myotis austroriparius – UNITED STATES. South Carolina: Francis Beidler Forest,

Dorchester County (FBF11). Georgia: Climax Cave, Decatur County (AM168).

Myotis leibii – UNITED STATES. West Virginia: North Fork Mountain, Pendleton

County (CS181).

Myotis lucifugus – UNITED STATES. Montana: Flathead National Forest, 0.5 mi

NW of Swan Lake, Lake County (ASK4402). West Virginia: Babcock State Park, 0.2

miles S, 0.3 miles W of Clifftop, Fayette County (CM102862). Nebraska: Guadalcanal

Prairie, 5.7 miles S and 3.5 miles W of Harrison, Sioux County (RB5828).

Myotis septentrionalis – UNITED STATES. Kentucky: Bangor, Rowan County

(EB95). Maryland: Owens Creek campground, Catoctin Mountain Park, Frederick

County (JJ43). Nebraska: Walnut Creek, 3.9 mile N and 4.4 miles W of Newcastle,

Dixon County (RB5610). West Virginia: Monongahela National Forest, 3 miles N,

4.5 miles W of Harmon, Randolph County (CM82047). North Fork Mountain, Pendleton

County (CS04). Camp Creek State Forest and Park, Mercer County (CS11).

CANADA. British Columbia: Smith River, N of Alaska Highway (UAM68932)

Myotis sodalis – UNITED STATES. Tennessee: White Oak Blowhole Cave, Blount

County (MYSO304). Virginia: Cumberland Gap Saltpeter Cave, Lee County

(MYSO330).

The Southeastern Naturalist is a peer-reviewed journal that covers all aspects of natural history within the southeastern United States. We welcome research articles, summary review papers, and observational notes.

The Southeastern Naturalist is a peer-reviewed journal that covers all aspects of natural history within the southeastern United States. We welcome research articles, summary review papers, and observational notes.