Southeastern Naturalist

G.D. Constantz

2015 Vol. 14, Special Issue 7

405

Canaan Valley & Environs

2015 Southeastern Naturalist 14(Special Issue 7):405–427

Prehistory of Canaan Valley: An Ecological View

George D. Constantz*

Abstract - To place the prehistoric people of Canaan Valley (hereafter, the Valley), WV,

in spatial and temporal contexts, I reviewed general trends in climate, environment, technology,

and society through the major periods of prehistory. A network of trails integrated

the people of the Valley area within broader regional trends. Based on the widespread

patterns, inferences of local environments and natural resources, and findings at local

archeological sites—including recently discovered prehistoric artifacts in the Valley—I

synthesized a general theory about the ecology of prehistoric people of the Valley area:

from settlements in optimal habitats of the Cheat and/or South Branch Potomac River

floodplains, people occupied the sub-optimal habitat of the Valley for extended stays

(e.g., one or two months) during annual migrations, for brief stopovers (one or two days)

while central-place foraging, or both. From this general model, I derived several specific

hypotheses, most of which are testable with current archaeological methods. I conclude

by comparing the environmental ethics of prehistoric and modern inhabitants of the

Valley. This review will help residents and visitors appreciate the Valley’s prehistoric

forerunners, commercial developers minimize archaeological impacts, and public land

managers design interpretive exhibits.

A Point of View

Biologists have a long tradition of applying the theories of ecology, animal

behavior, and evolutionary biology to interpret the human condition (e.g., Darwin

1871, Diamond 1992, Ehrlich 2000, Morris 1967, Wilson 1978). Two beliefs

have supported this approach: (a) Homo sapiens and other modern primates

evolved from a common ancestor, and (b) humans and other animals have interacted

with environmental factors in fundamentally similar ways.

I am one of those biologists, with interests in the evolutionary ecology

of Appalachian animals (Constantz 2004). From this perspective, I offer an

ecological interpretation of prehistoric humans in Canaan Valley (hereafter,

the Valley).

Time Periods

Archaeologists divide the human past into periods distinguished by cultural

indicators. I assembled general descriptions of the following major periods from

several sources (Fagan 2000; Gardner 1986; Ison et al. 1985; Lesser 1993; Mc-

Michael 1968; Niquette and Henderson 1984; Sullivan and Prezzano 2001a;

Thomas 1993, 1994).

*Research and Development Program, Canaan Valley Institute, PO Box 673, Davis WV

26260. Current address - 351 North Back Creek Road, High View WV 26808; constantz@

frontiernet.net.

Southeastern Naturalist

G.D. Constantz

2015 Vol. 14, Special Issue 7

406

Paleo-Indian Period (12,500–11,000 years before present [YBP])

Towards the end of the Pleistocene Epoch (1.8 million to 10,000 YBP), at

full Wisconsin glaciation, a tundra-like environment existed at least 180 mi

(300 km) south of the ice margin at elevations as low as 2706 ft (820 m). The

Valley, which lies about 135 mi (225 km) south of southern-most extent of the

ice front (Van Diver 1990) and situated at 3218 to 4323 ft (975–1310 m) in elevation,

would have been within this periglacial region. During this epoch, a

diverse set of large-bodied mammals, including Nothrotheriops (ground sloth),

Glyptodon (giant armadillo), Canis (dire wolf), Arctodus (short-faced bear),

Smilodon (saber-toothed tiger), Mammuthus (woolly mammoth), Mammut

(mastodon), Equus (horse), Tapirus (giant tapir), Camelops (camel), Rangifer

(caribou), Alces (moose), Cervus (elk), Bison (bison), and Symbos (musk

oxen), roamed North America (Kurten 1976).

Studies of prehistoric human teeth, nuclear and mitochondrial DNA, virus

strains, and languages support the theory that the first Americans immigrated

from Siberia (Diamond 1987). Human artifacts dated at 25,000 and 12,000 YBP

have been found at Beringia’s western (Siberia) and eastern (Alaska) ends, respectively.

It is consistent that the first humans in eastern North America used

the core- and blade-based technology that was standard in the Upper Paleolithic

of Eurasia (Carr et al. 2001).

At the end of the Pleistocene, the climate began warming. In the Mid-Atlantic

Highlands, the boreal spruce forest replaced tundra by 12,700 YBP (Lesser 1993,

Yahner 1995), and the boreal forest was in turn succeeded by a mixed coniferousdeciduous

forest by 10,500 YBP, near the time of human arrival.

The Canadian ice sheet between Alaska and the contiguous US partly melted

at 11,700 YBP to yield a long and narrow, north–south, ice-free corridor just

east of the Rocky Mountains (Pielou 1991). Some early Americans probably

dispersed southward through this gap, while others may have arrived via Pacific

coastal routes. Within a few centuries, the distinctive stone weapon called Clovis

fluted point appeared throughout North and Central America (Flannery 2001).

People spread 9600 mi (16,000 km), from Alaska to Patagonia, within 1000

years, an average dispersal rate of 9.6 miles (16 km) per year. This swift spread is

why the entire Clovis toolkit is virtually identical throughout North America. The

Appalachians were initially penetrated by humans around 12,000 YBP (Carr et

al. 2001). Possible pre-Paleo-Indian artifacts at Meadowcroft Rockshelter in the

Appalachian Plateau province of southwestern Pennsylvania, about 90 mi (150

km) northwest of the Valley, have been dated at 17,000 YBP (Adovasio and Page

2002, Adovasio et al. 1990, Sullivan and Prezzano 2001b), but several critics assert

the samples were contaminated. A pre-Clovis presence is supported by two

other sites: (1) Monte Verde, Chile at 12,500 to 13,000 YBP; and (2) Hell Gap,

WY at more than 12,000 YBP (Carr et al. 2001).

Terminal dates of the Clovis horizon are close to those for the extinction of

35 to 40 species of large-bodied mammals. This synchronicity led some paleoecologists

to champion the overkill hypothesis, which suggests that Clovis

Southeastern Naturalist

G.D. Constantz

2015 Vol. 14, Special Issue 7

407

hunters exterminated much of the Pleistocene megafauna (Martin 1984).

Alternately, perhaps additively, they died out because of climatic warming

(Flannery 2001).

Eastern Paleo-Indians seem to have followed a more diverse hunting-gathering

subsistence strategy than their western big-game hunting contemporaries

(Thomas 1994, Walker et al. 2001). More regionally, from small sites in

major stream valleys, especially along the eastern and western flanks of the

Appalachians (Lane and Anderson 2001), they exploited nuts, hackberries,

fish, waterfowl, and small mammals in a lifeway called “broad-spectrum foraging”

(Carr et al. 2001). It is consistent that in the East fluted points have not

been recovered in association with the remains of large Pleistocene mammals.

Rather, Eastern Paleo-Indians, persisting as thinly scattered mobile multi-family

bands, produced a great variety of fluted points. This comparatively higher

diversity of projectile points has been labeled the “eastern fluted point tradition”

(Fagan 2000).

In the East, Clovis points have been unearthed in Nova Scotia, Massachusetts,

Pennsylvania, Illinois, along the Ohio River, and in Kentucky, Virginia, Tennessee,

Georgia, and Alabama. Although Paleo-Indians were rare in the Appalachian

Mountains (Turner 1984), possibly because they generally avoided heavily dissected

uplands (Brashler 1984, Bush 1996), fluted points have been found in West

Virginia along the Lower Monongahela River and at the Ohio River in Parkersburg,

and more locally at Judy Gap and Marlinton and in Preston County (Lesser

1993). The Paleo-Indian extended-use site closest to the Valley may have been

about 60 mi (100 km) east along the Shenandoah River.

Archaic Period (11,000–3,000 YBP)

The climate continued warming until only the highest summits supported

Picea spp. (spruce) and Abies spp. (fir). Throughout much of the Mid-Atlantic

Highlands, the ecological transition from spruce-pine boreal forest to the mesic

oak-hickory community was completed during 10,000 to 9000 YBP (Braun 1950,

Lane and Anderson 2001). With temperatures similar to those of higher latitudes,

the Valley’s cold humid climate has functioned as a refugium for boreal plants.

Growing human populations began to concentrate in the region’s floodplains.

In the Appalachian Plateau physiographic province, which includes the Valley,

streams run through narrow V-shaped valleys, so large floodplains were

an uncommon habitat (Wall 1981). Archaic sites have been uncovered in large

floodplain areas along the Cheat, Tygart Valley, and South Branch Potomac rivers

(Fig. 1; Brashler 1984).

A hallmark of the Archaic Period was subsistence generalization. Hunting

was deemphasized. In contrast to the specialized fluted point designed for hunting

big animals, Archaic toolkits were more diverse. At minimal energy expense,

gardening diversified their foods. Eastern Archaic people also relied on nuts, like

hickory and black walnut, because they could be collected efficiently and yielded

almost five times the energy as the same mass of lean meat (Ison 1996).

Southeastern Naturalist

G.D. Constantz

2015 Vol. 14, Special Issue 7

408

A band’s annual movements appear to have been based on exploiting multiple,

diffuse resources (Cleland 1976). Through seasonal rounds, people moved

between year-round floodplain base camps and temporary specialized upland

resource-collection camps. An abundant, temporarily available mass resource in

the uplands along the Shenandoah Valley, for example, was fruits of Castanea

dentata (Marsh.) Borkh. (American Chestnut). Stated in a different way, extensified

uses of the uplands may have been part of tethered nomadism, in which base

camps were the focus of increasingly sedentary occupations, from which shortterm

forays were made to upland procurement sites (Custer 1996).

Versaggi et al. (2001) developed such a settlement-subsistence model for the

Late Archaic in the Susquehanna Valley. Overnight upland sites were used by daily

foragers, possibly women, who ranged out of residential base camps on valley

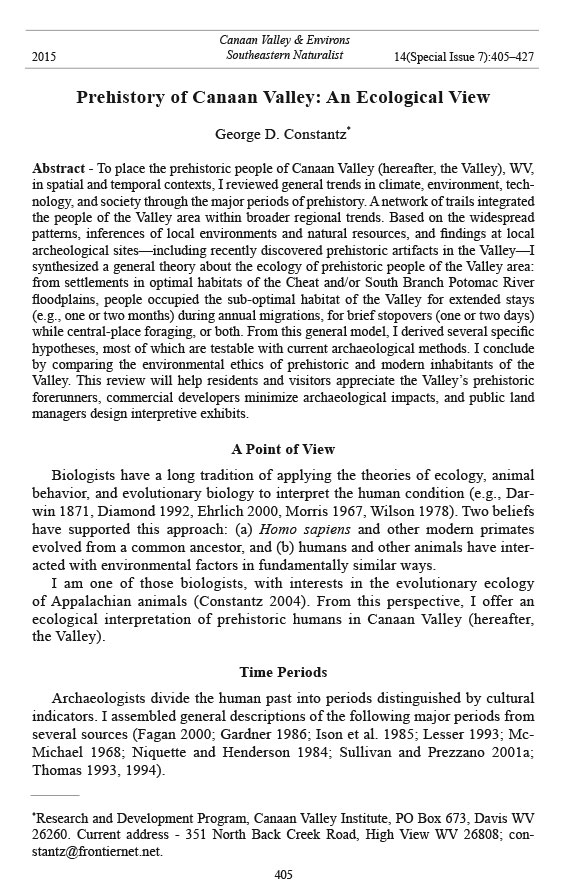

Figure 1. Floodplains and possible chert sources near Canaan Valley. Symbols: o = possible

outcrop of Greenbrier chert, solid triangle = South Branch Potomac complex, open

triangle = Horseshoe Bend complex, open star = Greenland Gap, dashed line = crest of

Allegheny Front. Acronyms: TVC = Tygart Valley complex, FRQ = Files Run quarry,

LRQ = Limekiln Run quarry, GL = Greenbrier limestone (shown as dark gray), HL =

Helderberg limestone (light gray).

Southeastern Naturalist

G.D. Constantz

2015 Vol. 14, Special Issue 7

409

floors for procuring and processing seasonally aggregated foods. Increasing sedentism

allowed each group to adapt its own brand of subsistence for exploiting

local resources. By the Late Archaic, local specialization had generated stylistic

regionalization of artifacts (Sullivan and Prezzano 2001b). Other trends included

greater levels of the following cultural characteristics: population, specialization

and efficiency, cultural complexity, interregional trade (in Late Archaic), and

mortuary ceremonialism (Gardner 1996).

The Archaic Period featured several technological innovations: (1) mortar and

pestle for grinding nuts and seeds into meal, which was easier to digest, transport,

and store; (2) the linked package of notched and stem points and the atlatl, which

is a spear thrower that generates more force and is more accurate than a handimpelled

spear; (3) chipped stone axe (introduced at 8000 YBP), for chopping,

digging, skinning, and other purposes, which was more versatile than the groundstone

axe because it held an edge better; (4) twist drill for piercing stone and bone;

(5) stone bowl (introduced at 3000 YBP) for cooking on hot rocks, but which was

probably too heavy to move from base camp; and (6) use of two complexes of

plant cultigens (cultivated varieties)—(a) native plants like goosefoot, marsh elder,

and sunflower, and (b) non-native species like gourd, squash, and corn.

In the East, the general Archaic sequence has been uncovered in the Shenandoah

Valley of Virginia, at St. Albans in southwestern West Virginia, through the

central Ohio River valley, and in Tennessee and North Carolina. More locally, Archaic

sites have been found in the transition zone between the Ridge and Valley

and Appalachian Plateau provinces, and in the floodplains of the Cheat, Tygart

Valley, and South Branch Potomac rivers.

Woodland Period (3000–800 YBP)

The Woodland Period’s climate was essentially the same as today’s. The

Valley averages 24 °F (-4 °C) in air temperature and 3.6 inches (9 cm) of precipitation

in January; July’s means are 67 °F (19 °C) and 5.3 inches (13 cm),

respectively (Stephenson 1993a). Annually, the Valley averages 122 inches (305

cm) of snowfall, 90 frost-free days, and 160 cloudy days (80–100% cloud cover).

Freezing temperatures can occur in any month.

The Valley is within the Allegheny Mountain Section of West Virginia. This

section, with deep valleys and the state’s highest elevations and heaviest rainfalls,

supports a set of plants classified as the Northern Forest, which in turn can

be subdivided into two community types (Clarkson 1964, Stephenson 1993b,

Strausbaugh and Core n.d.):

1) The Northern Evergreen Forest – Picea rubens Sarg. (Red Spruce), the

most distinctive representative of this plant community type, was formerly

abundant on mountaintops and plateaus. The Valley supported one of the

finest climax Red Spruce forests in the East (Fortney 1993). Other trees

include Abies balsamea (L.) Mill. (Balsam Fir), Tsuga canadensis (L.)

Carrière (Eastern Hemlock), Betula alleghaniensis Britt. (Yellow Birch),

and Sorbus americana Marshall (American Mountain-ash). Frequent fog,

Southeastern Naturalist

G.D. Constantz

2015 Vol. 14, Special Issue 7

410

cold temperatures, and abundant precipitation contributed to the development

of this forest. Forests of this type were extremely dense and featured

giant trees 6.6 ft (2 m) in diameter and 132 ft (40 m) tall. Heath thickets

made parts of the Valley almost impassable.

2) Northern Hardwood Forest – This community type, which covers

extensive areas with rich moist loamy soil, occurs below the Northern Evergreen

Forest and above 3020 ft (915 m) in elevation. This plant community

includes Yellow Birch and Betula nigra L. (Black Birch), Acer saccharum

Marshall (Sugar Maple) and A. rubrum L. (Red Maple), Fagus grandifolia

Ehrh. (American Beech), Tilia americana L. (American Basswood), Eastern

Hemlock, Pinus strobus L. (Eastern White Pine), Fraxinus americana L.

(White Ash), Prunus serotina Ehrh. (Black Cherry), Magnolia acuminata

L. (Cucumbertree), Liriodendron tulipifera L. (Tulip Poplar), and Quercus

rubra L. (Northern Red Oak) and Q. prinus L. (Chestnut Oak).

Woodland peoples’ foods came increasingly from gardened cultigens and foraged

wild plants. Effective storage of surplus corn, beans, squash, and sunflower

sustained scattered hamlets sited in floodplains. During seasonal rounds that

integrated hunting, fishing, horticulture, and plant gathering, the uplands were

used for short-term hunting and gathering.

In the East, the shift from reliance on wild plants and animals to food production

economies passed through several stages (Smith 1989): (1) domestication

of four plant species (listed in the paragraph above) during 4000 to 3000 YBP,

(2) emergence of food production economies between 2250 and 1800 YBP, and

(3) a rapid, broad-scale shift to agriculture dominated by non-indigenous maize

during the 300 years starting at 1200 YBP.

Cultural trends included increasing levels of floodplain occupation, aggregation

of dispersed single-household hamlets into larger settlements, sedentism,

agriculture, food storage, stone-mound burials, inter-regional trade, and potterymaking.

The uplands were used less during the Woodland Period (Cunningham

1983, Stewart 1983, Wall 1981). By 1000 YBP, diverse and vibrant cultures occupied

the Appalachian Mountains.

Late Prehistoric (800–450 YBP) and Protohistoric (450–300 YBP) periods

Some archaeological classifications include the Late Prehistoric and Protohistoric

periods. Late Prehistoric people maintained palisaded villages in

floodplains, relied on corn agriculture, and used small camps on upland stream

terraces. Just antedating recorded history, Protohistoric people had access to

European trade goods but no direct contact with Europeans. In southwestern

West Virginia, some Protohistoric villages featured burials with pottery

(Maslowski 1984).

Historic Period (350 YBP–present)

How many native North Americans were living in 1491? Estimates range

widely, from 900 thousand to 18 million (Verano and Ubelaker 1991), in part

because many died before a first estimate was possible. The indigenous human

Southeastern Naturalist

G.D. Constantz

2015 Vol. 14, Special Issue 7

411

genome conferred little resistance to some Old World diseases like smallpox,

measles, cholera, diphtheria, typhoid fever, and influenza (Horse Capture 1991).

Swift hemisphere-wide pandemics started at points of contact with the first explorers

and traders. Native populations were reduced by 50 to 90 percent (Viola

1991) and cultural systems changed profoundly (Henderson 1992), all before

literate observers arrived (Diamond 1998).

By the start of the Historic Period, aboriginal people appear to have abandoned

most of West Virginia. Although several reasons for this hiatus have been

offered, such as the holocaust from infections, depopulation by the Iroquois

Confederacy, and westward displacement by aggressive Europeans, the causes

remain a mystery.

Trails

The rapid spreading of Paleo-Indian fluted points, Archaic atlatls, Woodland

horticulture, and human pathogens was presumably facilitated by a network

of trails (Fig. 2; Haynes 1996). Via trails, people of the western Mid-Atlantic

participated in a larger cultural sphere that shared ideas, tools, and other cultural

elements (Gardner 1984). In a heavily dissected region with a dendritic

drainage pattern, like the Valley area, travel occurred along ridges and stream

bottoms (Bush 1996), part of a Native American trail system that would eventually

form the basis of many of our modern mountain highways (Sullivan and

Prezzno 2001c). The resulting cultural diffusion contributed to a regional identity

(Sullivan and Prezzano 2001c).

Figure 2. Trails potentially used by prehistoric people of the Canaan Valley area.

Southeastern Naturalist

G.D. Constantz

2015 Vol. 14, Special Issue 7

412

Facilitated by trails, prehistoric people of the Mid-Atlantic uplands participated

in an extensive trade network that reached from the east coast to the Rocky

Mountains and from the Great Lakes to the Gulf of Mexico. Valued rocks, like

cherts from Ohio, flints from Illinois, and obsidian from Yellowstone, were

passed hand to hand, from one band to another, over hundreds, even thousands,

of miles (Fagan 2000, Thomas 1994). Other trade items included mica from

North Carolina, copper from the Great Lakes, and mollusk shells from the Gulf

of Mexico. All of these items have been discovered at prehistoric sites within the

cultural sphere that includes the Valley.

A dominant path, known as the Great Warrior Trail, extended along the grain

of the Appalachians from New York to Alabama (Sullivan and Prezzano 2001a).

Probably functioning by 5000 YBP, this well-worn route enabled the movement

of commodities, people, and ideas (Watson 2001).

Projectile points from all prehistoric periods have been recovered from West

Virginia and adjacent areas (Lesser 1993). Because its artifact assemblages reflect

cultural influences from the Ohio Valley, the northeast, and the southeast,

the Mid-Atlantic Highlands appear to have been a melting pot of the prehistoric

cultures of eastern North America.

Therefore, because North America was crisscrossed by trails, which presumably

facilitated the movement of people, valued items, and ideas over vast

distances, prehistoric Canaan Valleyans were part of the regional, even continental,

cultural trends that characterized the major prehistoric periods.

Archaeological Sites

The distribution of archaeological sites throughout the the Valley region suggests

an interesting pattern (Fig. 3). As I have said, multiple sites have been found

in major valleys along the Cheat, Tygart Valley, and South Branch Potomac rivers.

In contrast, the upland areas have yielded few prehistoric sites.

To illustrate the diversity of prehistoric land uses in the Mid-Atlantic Highlands,

I summarize the findings at four archaeological areas.

Cheat River area

This area encompasses a series of 31 sites along 33 mi (55 km) of the Cheat

River, 12 mi (20 km) west of the Valley (Jensen 1970). Although this area has

yielded no evidence of Paleo-Indians, two fluted points have been found in neighboring

Preston County. The earliest evidence of humans in this area is within

Horseshoe Bend at 8200 YBP. The area was next occupied at 7500 YBP, possibly

by nomadic hunting families. The area’s projectile points suggest immigration

from, or trade with, the South. Woodland signs include stone burial mounds and

limestone tempered pottery. These people lived in small villages with an economy

based on hunting and corn-beans-squash agriculture. The important Seneca

Trail crossed the Cheat River at Horseshoe Bend (Fig. 2). During 1000 to 400

YBP, people of the Monongahela culture lived here in fortified villages, hunted

with small triangular points that were probably propelled by bow and arrow, and

Southeastern Naturalist

G.D. Constantz

2015 Vol. 14, Special Issue 7

413

practiced sophisticated horticulture. By 300 YBP, the Cheat River area had emptied

of people.

Burnsville Reservoir area

This area is composed of 23 sites along 9.6 miles (16 km) of the Little Kanawha

River and is 66 mi (110 km) southwest of the Valley (Broyles et al. 1975, Fitzgibbons

et al. 1979). Even though it was occupied from 10,500 YBP to the early 17th

century, and is located in wide valley areas with tributaries and terraces, it appears

that no site was more than a seasonal camp or bivouac. Some spots served for lithic

reduction, which is the crafting of tools from raw stone. This area’s artifact assemblage

reflects affinities with the Carolina piedmont and upstate New York.

Tygart Valley River sites

Three sites, located on the western slope of Cheat Mountain 27 mi (45 km)

southwest of the Valley, supported prehistoric lithic technologies. (1) At the Files

Run Quarry site, the Greenbrier Formation features exposed nodules of chert, a

stone that local people began using in the Early Archaic (Lesser 1988). Although

Greenbrier chert is only fair to mediocre in its knapping qualities, it may have

been the best stone available locally. The site’s debitage assemblage indicates

intense or long-term activity. Nodules were collected or extracted, then moved to

a reduction station below and adjacent to the quarry, as well as to another reduction

station 2.4 mi (4 km) southwest of the quarry. Multicomponent sites within

5.7 mi (9.5 km) have also yielded Greenbrier chert points. (2) The Limekiln Run

Figure 3. Archeological sites relevant to interpreting the prehistory of Canaan Valley.

Gray triangles indicate locations of individual sites. Larger, open circles and oval indicate

locations of complexes.

Southeastern Naturalist

G.D. Constantz

2015 Vol. 14, Special Issue 7

414

site, located on a sandstone bench less than 330 ft (100 m) below an outcrop of

Greenbrier limestone, served as a reduction and manufacturing station (Brashler

and Lesser 1985). Artifacts suggest that the chert was extracted and moved below

to be reduced from raw material to tools. (3) The Hill site is a typical example of

an Archaic settlement in the floodplains. Most of its debitage consists of Greenbrier

chert (Lesser 1986).

The Valley

A more recently discovered site is located on the east side of West Virginia

Route 32 in the Valley itself, on a small knoll near a spring at an elevation of 3251

ft (985 m) (Traver et al. 2002). In June 2002, over 200 shovel test pits yielded 15

prehistoric artifacts, including three types of chert flakes and a fragment of a bifacial

tool (R.F. Hoffman, MAAR Associates, Newark, DE, pers. comm.). Based

on local lithology, the chert is probably not local. Although the artifacts could not

be affiliated with a specific culture, the lack of ceramics is consistent with an Archaic

culture (R.F. Hoffman, pers. comm.). The pattern of lithic scatter suggests

the site hosted at least two brief stopovers for hunting and curation of stone tools.

Neither fire-cracked rock, ground or stone pecked stone tools, pottery sherds, nor

evidence of a village or base camp was found.

Although four projectile points had previously been found near this site, the

present paper seems to be the first published report of prehistoric artifacts in

the Valley. Why have so few artifacts been found in the Valley? The most obvious

possibilities are inadequate archaeological sampling and scant prehistoric use. I

will discuss this more in following sections.

The prehistoric site in the Valley is an example of a small lithic scatter, the

most common site type in the uplands (Turner 1996, Wall 1996). Other lithic

scatter sites have yielded primary reduction, secondary, and retouch flakes, and

seem to have supported tasks like stone procurement, biface reduction, and tool

resharpening (Custer 1996, Tourtellotte 1996). Upland lithic scatters may have

been left by specialized parties who knew the area’s resources and used the uplands

for procuring resources (Haynes 1996).

Both the general patterns of space use during the major prehistoric periods

and the specific findings at local sites suggest that prehistoric people occupied

the Valley for short periods.

Why Did Prehistoric People Visit The Valley?

Prehistoric people may have used the Valley for several possible reasons,

including the availability of plentiful water, escape from parasites, gathering of

psychoactive plants or specialized materials for baskets, and as a refuge from aggressive

bands, but possibly the most significant were acquiring stone and food.

Stone

Prehistoric knappers made tools by removing flakes from a stone by hitting it

with a harder stone or with a bone (Gardner 1986). In some cases, the flake was

Southeastern Naturalist

G.D. Constantz

2015 Vol. 14, Special Issue 7

415

the desired tool; in other cases the piece remaining, or core, would be fashioned

into a tool. In the East, raw forms of valued stone appear to have anchored centrally

based wandering societies (Fagan 2000), a relationship that may explain a

strong statistical correlation between Paleo-Indian sites and lithic sources (Bush

1996). If certain kinds of stone were needed for specific applications, the location

of material would have restricted the distribution of people, or may have caused

them to range great distances to acquire it (Haynes 1996). In contrast to the various

kinds of useful stones in the Ridge and Valley province, only Greenbrier chert

was available west of the Allegheny Front (Fig. 1; Brashler 1984, Haynes 1996).

High-quality chert deposits almost always show evidence of prehistoric

use. The three chert sites on Cheat Mountain described above are examples of

quarries, defined as camps occupied for the extraction of rock from outcrops

(Turner 1984).

The raw stone materials in a prehistoric site closely reflect the predominant

geologic composition of the local (e.g., within 9 to 12 mi [15–20 km]) area

(Haynes 1996). Greenbrier chert nodules were formed from the siliceous spicules

of sponges that lived in the open ocean, but such depositional environments did

not exist at the relevant time in the Valley’s region (T.C. Wynn, Lock Haven University

of Pennsylvania, Lock Haven, PA and D.L. Matchen, Concord University,

Athens, WV, pers. comm.). The source of Greenbrier chert closest to the Valley

may have been the Tygart Valley quarries (Fig. 1). I conclude that prehistoric

people did not visit the Valley for stone.

Food

As I have said, eastern peoples were not specialized big-game hunters (Thomas

1993). Sticking close to river valleys, they systematically moved within their

home range, taking advantage of seasonally available plant and animal foods.

Such a generalized ecological adaptation may have buffered people against the

failure of any particular single food species.

The Valley appears to have offered a variety of animal foods. Potential game

mammals included Lepus americanus Erxleben (Snowshoe Hare), Sylvilagus

floridanus J.A. Allen (Eastern Cottontail) and S. transitionalis (Bangs) (New

England Cottontail), Tamiasciurus hudsonicus (Erxleben) (Red Squirrel) and

Sciurus carolinensis Gmelin (Gray Squirrel), Castor canadensis Kuhl (Beaver),

Ondatra zibethicus (L.) (Muskrat), Marmota monax (L.) (Woodchuck), Odocoileus

virginianus Zimmermann (White-tailed Deer), Bison bison (L.) (Woodland

Bison), Cervus elaphus L. (Elk), Mustela frenata Lichtenstein (Long-tailed Weasel),

Martes pennanti (Erxleben) (Fisher), Mustela vison (Schreber) (Mink), Lutra

canadensis (Schreber) (River Otter), Ursus americanus (Pallas) (Black Bear),

Lynx rufus (Schreber) (Bobcat), Puma concolor (L.) (Mountain Lion), Urocyon

cinereoargenteus (Schreber) (Gray Fox), and Canis lupus L. (Gray Wolf). Game

birds included Philohela minor Gmelin (Woodcock), Meleagris gallopavo L.

(Wild Turkey), Bonasa umbellus (L.) (Ruffed Grouse), Ectopistes migratorius

(L.) (Passenger Pigeon), Aix sponsa (L.) (Wood Duck), and several other Anas

(duck) species. Edible fishes included Catostomus commersoni Lacépède (White

Southeastern Naturalist

G.D. Constantz

2015 Vol. 14, Special Issue 7

416

Sucker), Hypentelium nigricans (Lesueur) (Northern Hog Sucker), Salvelinus

fontinalis (Mitchill) (Brook Trout), Ambloplites rupestris (Rafinesque) (Rock

Bass), Lepomis cyanellus Rafinesque (Green Sunfish) and L. macrochirus Rafinesque

(Bluegill), and Micropterus dolomieu Lacépède (Smallmouth Bass) and

M. salmoides (Lacépède) (Largemouth Bass) (Stauffer et al. 1995). Although

moderately diverse, these prey animals were thinly dispersed and thus did not

lend themselves to specialized, efficient exploitation (Brashler 1984).

Proposed Ecology of Prehistoric Humans in The Valley

Drawing from the broad regional trends and specific local findings, I synthesize

a holistic model of the ecology of prehistoric people (sensu Dancey 2001,

Lesser and Brashler 1996) in the Valley. From this general model, I extract

several testable hypotheses.

A general model

The world is a heterogeneous place. Envision the environment as a universe

of patches and gradients of dozens of variables (e.g., insolation, wind exposure,

temperature, moisture, acidity, nitrate concentration, three-dimensional

structure, predators, food species, competitors, parasites, pathogens) that present

living things with a variety of resources and constraints (Krebs 1972, Ricklefs

1990). In the case of the Appalachian Plateau, the landscape features patches of

rugged terrain, abundant water, temperate deciduous forest, rocky soils, high

biotic diversity, and narrow floodplains (Sullivan and Prezzano 2001b).

The prehistoric human animal was intimately connected to its patchy environment.

His or her life revolved around exploiting some resources (e.g., knappable

stone, hickory nuts, White-tailed Deer) and avoiding sites with limiting factors

(e.g., cold rain, thick mosquitoes, raiding bands). Like other animals, people

responded to spatial and temporal heterogeneity by selecting a few places for

long-term occupation while avoiding others.

The Valley lies in the unglaciated Allegheny Plateau subdivision of the Appalachian

Plateau physiographic province (Cremeens and Lothrop 2001). In such a

region of steep-sided valleys, narrow valley bottoms, and plateau tops, the most

habitable sites were found in stream valleys and rock shelters, and on benches

and ridgetops (Hasenstab and Johnson 2001).

An area with a floodplain, tributaries, and terraces, like that found along the

Cheat River, seems to have represented an optimal habitat for prehistoric people

(Fagan 2000, Gardner 1983). In contrast, people may have perceived the Valley

as sub-optimal. The Valley’s high elevation dictated cool air temperatures and a

short growing season; its concave form and heavy precipitation supported a high

water table and extensive wetlands; its tangled understory was hard to move

through; the humid forest was too fire resistant to create ecotones for game species

and sight lines for defense; and its rock outcrops offered no lithic sources.

Another factor in the Valley’s slight use may have been its distance from population

centers. Located in the mountainous interior, away from primary trails (sensu

Southeastern Naturalist

G.D. Constantz

2015 Vol. 14, Special Issue 7

417

Lane and Anderson 2001), the Valley was a day’s hike (about 12 straight-line miles

[20 km]) from settlements in the Cheat and South Branch Potomac floodplains.

Yet another reason for the Valley’s low inhabitance is that prehistoric

people may have rejected the “feel” of the Valley. In many animals, innate

predispositions (e.g., Partridge 1974) and juvenile experiences (e.g., Wecker

1964) are important in forming adult habitat preferences. Perhaps innate factors

provide the coarse tuning and learned factors the fine tuning in habitat

selection. Young adult hunter-gatherers, raised in semi-open floodplain villages,

may have disfavored the Valley’s thick structure, dark appearance, and

chilly air. Perhaps they favored open woodland, i.e., a savannah-like habitat

similar to that of our species’ African origins.

Even though prehistoric people may have shunned the Valley for several reasons,

the broad regional trends and specific local findings indicate they were in

the Valley for at least brief visits. Why were they there at all? How prehistoric

people used variable habitats can be viewed at several temporal scales. Annually,

groups of people may have followed flushes of food, occupying a series of

sites, each for an extended period (e.g., 1–2 months). At the daily scale, people

may have left their long-term, but possibly overexploited settled areas, hiked to

distant places to hunt and gather, and then returned quickly (e.g., 1–2 days) with

a load.

Annual migrations

Along the Shenandoah River in northern Virginia, the Flint Run complex was

intermittently occupied by Clovis people after 11,500 YBP. The site exhibits a

cultural continuum from Paleo-Indian into the Archaic (Gardner 1974, 1977,

1986). Its floodplain base camp included living areas with favorable wind and

sun, and a place where local jasper was fashioned into tools.

Within the Flint Run complex, the Thunderbird site was a central base for

mobile Paleo-Indians hunting throughout a broad range and then returning to the

same location. Prime hunting areas, lithic resource zones, and plant collecting areas

were periodically revisited. Jasper was abundant at nearby quarry sites. Away

from these base and quarry sites, the population dropped sharply. This pattern

of space use has been explained by the centrally-based wandering model (Kelly

1992). Applying this hypothesis, the Valley may have served as one in a series of

outlying foraging and hunting areas visited along an annual route.

From an ecological point of view, such seasonal rounds are a form of migration,

a type of behavior that allows organisms to exploit temporary resources

and avoid seasonal constraints (Ricklefs 1990). One type of migration, toand-

fro migration (Dingle 1996), may be most relevant. The mule deer, for

example, moves annually from high-elevation summer ranges to lower winter

ranges with shallower snow. This kind of migration may assume circular or

quasi-circular patterns with stops at several sites, each to exploit seasonally

available foods. To-and-fro migration, in which individuals learn to follow

routes that have been used over many generations, includes both lateral and

vertical movements.

Southeastern Naturalist

G.D. Constantz

2015 Vol. 14, Special Issue 7

418

In an ultimate evolutionary sense, an animal migrates because such movements

have contributed to the reproductive success of its ancestors in environments that

varied over space and time. One way to understand the adaptive significance

of migration is through cost-benefit analysis (Dingle 1996). Assuming the unit of

measurement is the number of offspring that in turn reproduce, if the benefit/

cost (b/c) of moving exceeds the b/c of staying, migration will be favored by

natural selection. A favorable b/c may occur if there are seasonal differences in

resources, e.g., bursts of food at various elevations in different seasons.

At the proximal level, people may have been stimulated to migrate by various

environmental cues, including daylength, temperature regime, and leaf-drop.

Such external signs may have triggered internal hormonal changes, which in

turn may have caused fat deposition and/or restlessness. During long-distance

migratory movements, people may have oriented by using natural landmarks like

astronomical patterns, mountain ridges, and streams; man-made rock cairns and

slashes on trees; and intracellular magnetic compasses in their brains.

And, finally, returning to an evolutionary archaeology point of view (Dancey

2001), it is possible that only some group members migrated. Prehistoric people

may have exhibited partial migration (Dingle 1996), in which only some moved

to the uplands while the rest stayed in the valley settlement. Who did the migrating

may have been influenced by genes, age, sex, or rank. For example, older

dominant men may have been more sedentary than younger subordinates.

Central-place foraging

Another way prehistoric people may have used the Valley is that they visited

here for brief stays of a day or two to hunt and gather in ways that maximized

their net energy intake. Optimal foraging maximizes net profit, i.e., benefits

minus costs (Pianka 1994). Optimal foraging theory assumes that individuals

maximizing their net energy gain leave more descendants on average than less

efficient individuals (Pyke et al. 1977). In an optimal feeding model, the animal

travels just far enough to supply its energy needs (Schoener 1971).

The ultimate currency for measuring optimal solutions is the number of

offspring that in turn reproduce (e.g., Alcock 1984, Williams 1966). In a more

proximal sense, benefits can be measured in net gains of matter and energy, and

costs can be measured in losses to predators, travel time not available for other

tasks, and the load weight (Krebs and Davies 1987). Assuming prehistoric people

in the Mid-Atlantic Highlands gathered food optimally (sensu Dunham 1996),

village-based hunting-gathering may have taken the form of central-place foraging.

In this kind of space use, food is acquired distantly and loads are returned

to a central site (Wetterer 1989). According to the central-place foraging model,

when travel time is shorter, the load that maximizes profit is smaller; conversely

load size should increase with distance (Krebs and Davies 1987). Prehistoric

people would not have hiked from Horseshoe Bend to the Valley for a pouch of

snowshoe hares; they intended to haul out large packages of energy, e.g., large

mammal carcasses.

Southeastern Naturalist

G.D. Constantz

2015 Vol. 14, Special Issue 7

419

It is appropriate that a Woodland contemporary, the Beaver, conforms to

some predictions of central-place foraging theory. Beavers cut a smaller range of

tree sizes (i.e., are increasingly selective) farther from their ponds (Fryxell and

Doucet 1991, Jenkins 1980). The hypotheses of annual migration and centralplace

foraging are not mutually exclusive. It is possible that migrants moved

through a series of extended-stay camps, and from each such camp they centralplace

foraged on a daily basis.

This discussion leads me to summarize a general ecological theory of prehistoric

peoples’ use of the Valley. Most people most of the time lived in the optimal

habitats of major river valleys. Because it was sub-optimal habitat, they only occasionally

visited the Valley. When they did use the Valley, it was as a stop along

an annual migration and/or as an outlier in central-place hunting of large-bodied

game. Proximal reasons for low visitation included behavioral avoidance and

long distances from population centers.

Specific hypotheses

The general model suggests 15 testable hypotheses. Under either the migration

or central-place scenario, the Valley:

1. offered only a few kinds or low densities of valued resources;

2. started to be used after optimal habitats (e.g., river valleys) were taken;

3. will yield no artifacts of long-term occupation, e.g., permanent dwellings

or gardens; and

4. was used during the most optimal times of the year, e.g., early summer.

Although annual migration and central-place foraging may be complementary,

each behavior generates the following hypotheses that could allow rejection

of either scenario. The former implies longer (e.g., one to two months) stays than

the latter (e.g., one or two days).

The annual migration hypothesis predicts that the Valley:

5. was used for many days (e.g., 30–60) at the same season each year;

6. will yield toolkits composed of some heavy items;

7. will reveal repeated-use hearths; and

8. provided diverse, but low-density plant and animal foods.

Under the central-place foraging model, the Valley:

9. provided large-bodied prey (e.g., deer, elk, bison) that were carried back

to permanent villages; small food items (e.g., nuts, brook trout, hares) were

eaten on site;

10. hosted brief (e.g., 1–2 days) visits after which users returned to more

permanent camps;

11. will yield few tools; if found, toolkits were made of traveling items;

12. will yield debitage reflecting on-the-go tool maintenance, and with no

re-use potential;

13. was used by non-established individuals, e.g., young males;

Southeastern Naturalist

G.D. Constantz

2015 Vol. 14, Special Issue 7

420

14. contains few or no hearths; if found, hearths were single-use; and

15. contains few or no prehistoric burials; if found, burial sites contain no

or few artifacts associated with long-term settlements.

Testing hypotheses five through 15 will help us determine whether the Valley

was occupied as a camp along an annual migration route, briefly while centralplace

foraging, or both. My subjective ecological judgment leads me to favor

the central-place foraging hypothesis. Most of these hypotheses are testable with

current archeological methods; one (13) must await new techniques. In broad

outline, my general model is consistent with Neumann’s (1992) partitioning of

205 South Branch Potomac sites into two clusters: (1) large, low drainage/low

elevation sites and (2) small, high drainage/high elevation sites. To the extent this

paper stimulates hypothetico-deductive tests of the general theory, I will consider

it a success.

A Comparison with Modern Humans

I close with a sociobiological resolution of an apparent paradox. The literatures

of aboriginal ethics and spirituality convey themes like “respect for the

environment” and “intimate connection to the land”. Their oral traditions seem

consistent. In Cherokee myth, an animal killed by a hunter after use of a chant

would come to life again, thereby avoiding the decline of game. “The frog does

not drink up the pond in which he lives.” Leaders felt responsible for seven generations

into the future (Shenandoah 1992).

Several modern scholars agree. Prehistoric Americans had a conservation

ethic (Noss and Cooperrider 1994) that included a holistic respect for nature

(Rockefeller and Elder 1992). The typical traditional American Indian attitude

was to regard all parts of the environment as enspirited, i.e., with consciousness,

reason, and volition (Callicott 1989). Rocks, trees, and insects had personalities

as fully as people.

Yet several lines of evidence suggest that Native Americans degraded their

environment. In the East, they slashed and burned forests to create canopy gaps

for growing crops, and then depleted soils until decreasing yields pushed them

elsewhere (Krech 1999). Fuel was exhausted, game became scarce. Like Indians

in other parts of North America (Botkin 1995), the Cherokee practiced periodic

burning of the forest (Silver 1996) to drive and kill deer, open travel corridors,

and create open security zones where enemies could be detected. But sometimes

they kindled destructive fires. More recently, some tribal governments have favored

resource extraction and other development projects even when they were

projected to have serious environmental impacts (Krech 1999).

How do we reconcile Native Americans’ (a) respect for the environment,

conservation ethic, and keen sense of interdependence; with their (b) depletion

of soils, over-hunting of game, and the setting of destructive fires? If we accept

the proposition that the evolutionary processes of natural selection, and its extensions

of sexual and kin selection, have functioned similarly in people of all

Southeastern Naturalist

G.D. Constantz

2015 Vol. 14, Special Issue 7

421

times (Trivers 1985, Wilson 1975), then prehistoric and modern inhabitants of

the Valley have had the same basic needs, motives, and responses. In humanistic

terms, we have been similarly contradicted—with differences among individuals

within groups, and with inconsistencies within each of us expressed at different

times. We have been hypocritical, short-sighted, and selfish; and also helpful,

far-sighted, and altruistic. Perhaps they were no better or worse than the average

person today.

Acknowledgments

I was helped by many generous people. Lee Avery, Ruth Brinker, John Calabrese,

Bob Hoffman, Hunter Lesser, David Matchen, Dewey Sanderson, and Tom Wynn shared

scientific insights. Doug Wood helped to map the trails. Friends at CVI, including Kip

Ambro, Beverli Badgley, Ryan Gaujot, Cindy Phillips, Ron Preston, Matt Sherald, Jocelyn

Smith, Ron Wigal, Paula Worden, and especially Ellen Voss, helped in various ways. Leah

Constantz, MAAR Associates, and Bob Maslowski provided literature. Nancy Ailes, Jim

Rawson, and two anonymous reviewers criticized the manuscript. Thanks to all.

Literature Cited

Adovasio, J.M., and J. Page. 2002. The First Americans: In pursuit of Archaeology’s

Greatest Mystery. Modern Library, New York, NY. 330 pp.

Adovasio, J.M., J. Donahue, and R. Struckenrath. 1990. The Meadowcroft Rockshelter

radiocarbon chronology 1975–1990. American Antiquity 55:348–354.

Alcock, J. 1984. Animal Behavior: An Evolutionary Approach, 3rd Edition. Sinauer Associates,

Sunderland, MA. 596 pp.

Botkin, D.B. 1995. Our Natural History: The Lessons of Lewis and Clark. G.P. Putnam’s

Sons, New York, NY. 300 pp.

Brashler, J.G. 1984. Exploitation of diffuse resources: Archaic settlement in mountainous

West Virginia. Pp. 5–24, In C.R. Geier, M.B. Barber, and G.A. Tolley (Eds.). Upland

Archeology in the East, Symposium No. 2. USDA Forest Service-Southern Region

and Archeological Society of Virginia, Richmond, VA. Special Publ. No. 38-Part 2.

Brashler, J.G., and W.H. Lesser. 1985. The Limekiln Run site and the reduction of

Greenbrier chert in Randolph County, West Virginia. West Virginia Archeology

37(1):27–40.

Braun, E.L. 1950. Deciduous Forests of Eastern North America. The Free Press, New

York, NY. 596 pp.

Broyles, B.J., E.R. Liddell, and D. Berry. 1975. Archeological survey and test excavations

in the Burnsville Reservoir, Braxton County, West Virginia. Prepared by the

West Virginia Geologic and Economic Survey, Morgantown, WV for the National

Park Service. 98 pp.

Bush, D.R. 1996. Rockshelter use at the headwaters of the Kentucky River. Pp. 100–135,

In C.R. Geier, M.B. Barber, G.A. Tolley, C. Nash, T.R. Whyte, and J. Herbstritt (organizers).

Upland Archeology in the East, Symposium No. 3. USDA Forest Service-

Southern Region and Archeological Society of Virginia, Richmond, VA. Special Publ.

No. 38-Part 3.

Callicott, J.B. 1989. In Defense of the Land Ethic: Essays in Environmental Philosophy.

State University of New York Press, Albany, NY. 325 pp.

Southeastern Naturalist

G.D. Constantz

2015 Vol. 14, Special Issue 7

422

Carr, K.W., J.M. Adovasio, and D.R. Pedler. 2001. Paleoindian populations in Trans-

Appalachia. Pp. 67–87, In L.P. Sullivan and S.C. Prezzano (Eds.). Archaeology of the

Appalachian Highlands. University of Tennessee Press, Knoxville, TN.

Clarkson, R.B. 1964. Tumult on the Mountains: Lumbering in West Virginia:1770–1920.

McClain Printing Co., Parsons, WV. 410 pp.

Cleland, C.E. 1976. The focal-diffuse model: An evolutionary perspective on the prehistoric

cultural adaptations of the eastern United States. Midcontinental Journal of

Archaeology 1(1):59–76.

Constantz, G. 2004. Hollows, Peepers, and Highlanders: An Appalachian Mountain

Ecology. 2nd Edition. West Virginia University Press, Morgantown, WV. 359 pp.

Cremeens, D.L., and J.C. Lothrop. 2001. Geomorphology of upland regolith in the

unglaciated Appalachian Plateau. Pp. 31–48, In L.P. Sullivan and S.C. Prezzano

(Eds.). Archaeology of the Appalachian highlands. University of Tennessee Press,

Knoxville, TN.

Cunningham, K.W. 1983. Prehistoric settlement-subsistence patterns in the Ridge and

Valley section of the Potomac highlands of eastern West Virginia—Hampshire, Hardy,

Grant, Mineral and Pendleton counties. Pp. 171–224, In C.R. Geier, M.B. Barber,

and G.A. Tolley (Eds.). Upland Archeology in the East, Symposium. No. 1. USDA

Forest Service-Southern Region and Archeological Society of Virginia, Richmond,

VA. Special Publ. No. 38-Part 1.

Custer, J.F. 1996. The highs and lows of “ephemeral” site archaeology in the Middle

Atlantic region. Pp. 169–188, In C.R. Geier, M.B. Barber, G.A. Tolley, C. Nash, T.R.

Whyte, and J. Herbstritt (Organizers). Upland Archeology in the East, Symposium

No. 3. USDA Forest Service-Southern Region and Archeological Society of Virginia,

Richmond, VA. Special Publ. No. 38-Part 3.

Dancey, W.S. 2001. An evolutionary view of Appalachian archaeology. Pp. 311–318, In

L.P. Sullivan and S.C. Prezzano (Eds.). Archaeology of the Appalachian highlands.

University of Tennessee Press, Knoxville, TN.

Darwin, C. 1871. The Descent of Man and Selection in Relation to Sex. Reprinted by The

Modern Library, Random House, New York, NY. Pp. 387–924.

Diamond, J.M. 1987. Who were the first Americans? Nature 329:580–581.

Diamond, J. 1992. The Third Chimpanzee: The Evolution and Future of the Human Animal.

Harper Perennial, New York, NY. 407 pp.

Diamond, J. 1998. Guns, Germs, and Steel: The Fates of Human Societies. W.W. Norton,

New York, NY. 480 pp.

Dingle, H. 1996. Migration: The Biology of Life on the Move. Oxford University Press,

New York, NY. 474 pp.

Dunham, G.H. 1996. Ordering space in the uplands: A review of Mid-Atlantic settlement

typologies. Pp. 336–349, In C.R. Geier, M.B. Barber, G.A. Tolley, C. Nash, T.R.

Whyte, and J. Herbstritt (Organizers). Upland archeology in the East, Symposium

No. 3. USDA Forest Service-Southern Region and Archeological. Society of Virginia,

Richmond, VA. Special Publ. No. 38-Part 3.

Ehrlich, P.R. 2000. Human Natures: Genes, Cultures, and the Human Prospect. Penguin

Books, New York, NY. 531 pp.

Fagan, B.M. 2000. Ancient North America: The Archaeology of a Continent. Thames and

Hudson, New York, NY. 544 pp.

Southeastern Naturalist

G.D. Constantz

2015 Vol. 14, Special Issue 7

423

Fitzgibbons, P.T., J.M. Adovasio, W.C. Johnson, F.J. Vento, and R.C. Carlisle. 1979.

Surficial archeology and aboriginal lithic technology of the Burnsville Reservoir,

Braxton County, West Virginia. Report prepared by the University of Pittsburgh for

the US Army Corps of Engineers, Huntington, WV. 295 pp.

Flannery, T. 2001. The Eternal Frontier: An Ecological History of North America and its

Peoples. Atlantic Monthly Press, New York, NY. 404 pp.

Fortney, R.H. 1993. Canaan Valley: An area of special interest within the upland forest

region. Pp. 47–65, In S.L. Stephenson (Ed.). Upland Forests of West Virginia. Mc-

Clain Printing Co., Parsons, WV.

Fryxell, J.M., and C.M. Doucet. 1991. Provisioning time and central-place foraging in

Beavers. Canadian Journal of Zoology 69:1308–1313.

Gardner, W.M. 1974. The Flint Run complex: Pattern and process during the Paleo-Indian

to early Archaic. Occasional Publications of the Catholic University of America,

Washington, DC. Pp. 5–47.

Gardner, W.M. 1977. The Flint Run Paleo-Indian complex and its implications for

eastern North American prehistory. Annals of the New York Academy of Science

288:257–263.

Gardner, W.M. 1983. What goes up must go down: Transhumance in the mountainous

zones of the Middle Atlantic. Pp. 2–42, In C.R. Geier, M.B. Barber, and G.A. Tolley

(Eds.). Upland Archeology in the East, Symposium No. 1. USDA Forest Service-

Southern Region and Archeological Society of Virginia, Richmond, VA. Special Publ.

No. 38-Part 1.

Gardner, W.M. 1984. External cultural influences in the western Middle Atlantic: A neodiffusionist

approach, or you never know what went on under the rhododendron bush

until you look. Pp. 118–146, In C.R. Geier, M.B. Barber, and G.A. Tolley (Eds.).

Upland Archeology in the East, Symposium. No. 2. USDA Forest Service-Southern

Region and Archeological Society of Virginia, Richmond, VA. Special Publ. No. 38-

Part 2.

Gardner, W.M. 1986. Lost Arrowheads and Broken Pottery: Traces of Indians in the

Shenandoah Valley. Thunderbird Publications, Front Royal, VA. 98 pp.

Gardner, W.M. 1996. Some observations on the Late Archaic. Pp. 301–307, In C.R.

Geier, M.B. Barber, G.A. Tolley, C. Nash, T.R. Whyte, and J. Herbstritt (Organizers).

Upland Archeology in the East, Symposium. No. 3. USDA Forest Service-Southern

Region and Archeological Society of Virginia, Richmond, VA. Special Publ. No. 38-

Part 3.

Hasenstab, R.J., and W.C. Johnson. 2001. Hilltops of the Allegheny Plateau. Pp. 3–18,

In L.P. Sullivan and S.C. Prezzano (Eds.). Archaeology of the Appalachian highlands.

University of Tennessee Press, Knoxville, TN.

Haynes, J. 1996. Lithic diversity in upland Virginia sites: Cultural and natural embeddedness.

Pp. 215–228, In C.R. Geier, M.B. Barber, G.A. Tolley, C. Nash, T.R. Whyte, and

J. Herbstritt (Organizers). Upland Archeology in the East, Symposium No. 3. USDA

Forest Service-Southern Region and Archeological Society of Virginia, Richmond,

VA. Special Publ. No. 38-Part 3.

Henderson, A.G. 1992. Dispelling the myth: Seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Indian

life in Kentucky. Register of the Kentucky Historical Society 90(1):1–25.

Horse Capture, G.P. 1991. An American Indian perspective. Pp. 186–207, In H.J. Viola

and C. Margolis (Eds.). Seeds of Change: A Quincentennial Commemoration. Smithsonian

Institution Press, Washington, DC.

Southeastern Naturalist

G.D. Constantz

2015 Vol. 14, Special Issue 7

424

Ison, C.R. 1996. Man-plant relationships during the Terminal Archaic along the Cumberland

Plateau. Pp. 86–99, In C.R. Geier, M.B. Barber, G.A. Tolley, C. Nash, T.R.

Whyte, and J. Herbstritt (Organizers). Upland Archeology in the East, Symposium

No. 3. USDA Forest Service-Southern Region and Archeological Society of Virginia,

Richmond, VA. Special Publ. No. 38-Part 3.

Ison, C.R., J.A. Railey, A.G. Henderson, B.S. Ison, and J. Rossen. 1985. Archeological

investigations at the Green Sulphur Spring site complex, West Virginia. Archeological

Report 108, submitted by the Department of Anthropology, University of Kentucky,

to the West Virginia Department of Highways, Charleston, WV.

Jenkins, S.H. 1980. A size-distance relation in food selection by Beavers. Ecology

61:740–746.

Jensen, R.E. 1970. Archeological survey of the Rowlesburg Reservoir area, West Virginia.

Report of Archeological Investigations No. 2, West Virginia Geologic and

Economic Survey, Morgantown, WV. 31 pp.

Kelly, R.L. 1992. Mobility/sedentism: Concepts, archaeological measures, and effects.

Annual Reviews of Anthropology 21:43–66.

Krebs, C.J. 1972. Ecology: The Experimental Analysis of Distribution and Abundance.

Harper and Row, New York, NY. 694 pp.

Krebs, J.R., and N.B. Davies. 1987. An Introduction to Behavioural Ecology, 2nd Edition.

Sinauer Associates, Sunderland, MA. 389 pp.

Krech, S., III. 1999. The Ecological Indian. W.W. Norton and Co., New York, NY. 318 pp.

Kurten, B. 1976. Life in the Ice Age: Prelude to today. Pp. 142–162, In S.L. Fishbein

(Ed.). Our Continent: A Natural History of North America. National Geographic Society,

Washington, DC.

Lane, L., and D.G. Anderson. 2001. Paleoindian occupations of the southern Appalachians.

Pp. 88–102, In L.P. Sullivan and S.C. Prezzano (Eds.). Archaeology of the

Appalachian Highlands. University of Tennessee Press, Knoxville, TN.

Lesser, W.H. 1986. The Hill site (46RD55): The Middle Archaic manifestation in the

Tygart Valley. West Virginia Archeologist 38(2):54.

Lesser, W.H. 1988. Preliminary investigations at Files Run Quarry (46RD114): Lithic

procurement and reduction in the Tygart Valley uplands. West Virginia Archeologist

40(2):24–39.

Lesser, W.H. 1993. Prehistoric human settlement in the upland forest region. Pp. 231–

260, In S.L. Stephenson (Ed.). Upland forests of West Virginia. McClain Printing Co.,

Parsons, WV.

Lesser, W.H., and J.G. Brashler. 1996. Can we go beyond site distribution? Cultural models

and lithic scatters from the eastern West Virginia uplands. Pp. 189–202, In C.R.

Geier, M.B. Barber, G.A. Tolley, C. Nash, T.R. Whyte, and J. Herbstritt (Organizers).

Upland Archeology in the East, Symposium No. 3. USDA Forest Service-Southern

Region and Archeological Society of Virginia, Richmond, VA. Special Publ. No. 38-

Part 3.

Martin, P. 1984. Prehistoric overkill: The global model. Pp. 354–403, In P.S. Martin and

R.G. Klein (Eds.). Quaternary Extinctions. University of Arizona Press, Tucson, AZ.

Maslowski, R.F. 1984. Protohistoric villages in southern West Virginia. Pp. 148–165,

In C.R. Geier, M.B. Barber, and G.A. Tolley (Eds.). Upland Archeology in the East,

Symposium No. 2. USDA Forest Service-Southern Region and Archeological Society

of Virginia, Richmond, VA. Special Publ. No. 38-Part 2.

Southeastern Naturalist

G.D. Constantz

2015 Vol. 14, Special Issue 7

425

McMichael, E.V. 1968. Introduction to West Virginia Archeology, 2nd Edition revised.

Education Series, West Virginia Geologic and Economic Survey, Morgantown, WV.

68 pp.

Morris, D. 1967. The Naked Ape: A Zoologist’s Study of the Human Animal. McGraw-

Hill Book Co., New York, NY. 252 pp.

Neumann, T.W. 1992. The physiographic variables associated with prehistoric site location

in the upper Potomac River basin, West Virginia. Archaeology of Eastern North

America 20:81–124.

Niquette, C.M., and A.G. Henderson. 1984. Background to the historic and prehistoric

resources of eastern Kentucky. Prepared by Environment Consultants, Inc. for the US

Department of Interior, Bureau of Land Management, Alexandria, VA. Pp. 27–67.

Noss, R.F., and A.Y. Cooperrider. 1994. Saving Nature’s Legacy: Protecting and Restoring

Biodiversity. Island Press, Washington, DC. 416 pp.

Partridge, L. 1974. Habitat selection in titmice. Nature 247:573–574.

Pianka, E.R. 1994. Evolutionary Ecology, 5th Edition. Harper Collins College Publishing,

New York, NY. 486 pp.

Pielou, E.C. 1991. After the Ice Age: The Return of Life to Glaciated North America.

University of Chicago Press, Chicago, IL. 366 pp.

Pyke, G.H., H.R. Pulliam, and E.L. Charnov. 1977. Optimal foraging: A selective review

of theory and tests. Quarterly Review of Biology 52:137–154.

Ricklefs, R.E. 1990. Ecology, 3rd Edition. W.H. Freeman and Co., New York, NY.

896 pp.

Rockefeller, S.C., and J.C. Elder (Eds.). 1992. Spirit and Nature: Why the Environment

is a Religious Issue. Beacon Press, Boston, MA. 226 pp.

Schoener, T.W. 1971. Theory of feeding strategies. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics

2:369–404.

Shenandoah, A. 1992. A tradition of thanksgiving. Pp. 15–23, In S.C. Rockefeller and

J.C. Elder (Eds.). Spirit and Nature: Why the Environment is a Religious Issue. Beacon

Press, Boston, MA.

Silver, T. 1996. In search of Iron Eyes: A historian reflects on the Cherokees as environmentalists.

Appalachian Voice (published by the Sierra Club’s Southern Appalachian

Highlands Ecoregion Task Force, Boone NC) Winter 1996:3, 18.

Smith, B.D. 1989. Origins of agriculture in eastern North America. Science

246:1566–1571.

Stauffer, J.R., Jr., J.M. Boltz, and L.R. White. 1995. The fishes of West Virginia. Proceedings

of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia 16:1–389.

Stephenson, S.L. 1993a. An introduction to the upland forest region. Pp. 1–9, In S.L. Stephenson

(Ed.). Upland Forests of West Virginia. McClain Printing Co., Parsons, WV.

Stephenson, S.L. 1993b. Upland forest vegetation. Pp. 11–34, In S.L. Stephenson (Ed.).

Upland Forests of West Virginia. McClain Printing Co., Parsons, WV.

Stewart, R.M. 1983. Prehistoric settlement patterns in the Blue Ridge province of Maryland.

Pp. 43–90, In C.R. Geier, M.B. Barber, and G.A. Tolley (Eds.). Upland Archeology

in the East, Symposium No. 1. USDA Forest Service-Southern Region and

Archeological Society of Virginia, Richmond, VA. Spec. Publ. No. 38-Part 1.

Strausbaugh, P.D., and E.L. Core. N.d. Flora of West Virginia, 2nd Edition. Seneca

Books, Grantsville, WV. 1079 pp.

Sullivan, L.P., and S.C. Prezzano (Eds.). 2001a. Archaeology of the Appalachian Highlands.

University of Tennessee Press, Knoxville, TN. 410 pp.

Southeastern Naturalist

G.D. Constantz

2015 Vol. 14, Special Issue 7

426

Sullivan, L.P., and S.C. Prezzano. 2001b. Introduction: The concept of Appalachian archaeology.

Pp. xix–xxxiii, In L.P. Sullivan and S.C. Prezzano (Eds.). Archaeology of

the Appalachian Highlands. University of Tennessee Press, Knoxville, TN.

Sullivan, L.P., and S.C. Prezzano. 2001c. A conscious Appalachian archaeology. Pp.

323–331, In L.P. Sullivan and S.C. Prezzano (Eds.). Archaeology of the Appalachian

Highlands. University of Tennessee Press, Knoxville TN.

Thomas, D.H. 1993. Chapter five: Life of the plains and woodlands. Pp. 78–95, In D.H.

Thomas, J. Miller, R. White, P. Navokov, Jr., and A.M. Josephy. The Native Americans:

An Illustrated History. Turner Publishing, Atlanta, GA.

Thomas, D.H. 1994. Exploring Ancient Native America: An Archaeological Guide.

Routledge, New York, NY. 314 pp.

Tourtellotte, P.A. 1996. Upland lithic scatters in the Big Mountain-Stony Creek vicinity

of western Giles County, Virginia. Pp. 203–214, In C.R. Geier, M.B. Barber, G.A.

Tolley, C. Nash, T.R. Whyte, and J. Herbstritt (Organizers). Upland Archeology in the

East, Symposium No. 3. USDA Forest Service-Southern Region and Archeological

Society of Virginia, Richmond, VA. Spec. Publ. No. 38-Part 3.

Traver, J.D., R.A. Thomas, and R.F. Hoffman. 2002. Phase I archaeological identification

survey at the proposed maintenance building at Canaan Valley National Wildlife

Refuge, Tucker County, West Virginia. Prepared by MAAR Associates, Newark, DE,

for the US Fish and Wildlife Service, Hadley, MA.

Trivers, R. 1985. Social Evolution. Benjamin/Cummings Publishing Co., Menlo Park,

CA. 462 pp.

Turner, E.R. 1984. A synthesis of Paleo-Indian studies for the Appalachian Mountain

province of Virginia. Pp. 205–219, In C.R. Geier, M.B. Barber, and G.A. Tolley

(Eds.). Upland Archeology in the East, Symposium No. 2. USDA Forest Service-

Southern Region and Archeological Society of Virginia, Richmond, VA. Special Publ.

No. 38-Part 2.

Turner, E.R. 1996. Assessing the archaeological significance of prehistoric lithic scatters

in Virginia. Pp. 229–232, In C.R. Geier, M.B. Barber, G.A. Tolley, C. Nash, T.R.

Whyte, and J. Herbstritt (Organizers). Upland Archeology in the East, Symposium

No. 3. USDA Forest Service-Southern Region and Archeological Society of Virginia,

Richmond, VA. Spec. Publ. No. 38-Part 3.

Van Diver, B.D. 1990. Roadside Geology of Pennsylvania. Mountain Press, Missoula,

MT. 352 pp.

Verano, J.W., and D.H. Eubelaker. 1991. Health and disease in the pre-Columbian world.

Pp. 208–223, In H.J. Viola and C. Margolis (Eds.). Seeds of Change: A Quincentennial

Commemoration. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, DC.

Versaggi, N.M., L. Wurst, T.C. Madrigal, and A. Lain. 2001. Adding complexity to Late

Archaic research in the northeastern Appalachians. Pp. 121–133, In L.P. Sullivan and

S.C. Prezzano (Eds.). Archaeology of the Appalachian Highlands. University of Tennessee

Press, Knoxville, TN.

Viola, H.J., 1991. Seeds of change. Pp. 11–15, In H.J. Viola and C. Margolis (Eds.).

Seeds of Change: A Quincentennial Commemoration. Smithsonian Institution Press,

Washington, DC.

Walker, R.B., K.R. Detwiler, S.C. Meeks, and B.N. Driskell. 2001. Berries, bones, and

blades: Reconstructing Late Paleoindian subsistence economy at Dust Cave, Alabama.

Midcontinental Journal of Archaeology 26:169–197.

Wall, R. 1981. An archaeological study of the Maryland coal region: The prehistoric

resources. Maryland Geologic Survey, Baltimore, MD. 183 pp.

Southeastern Naturalist

G.D. Constantz

2015 Vol. 14, Special Issue 7

427

Wall, R.D. 1996. Lithic scatters along the Allegheny Front in West Virginia and Maryland.

Pp. 233–249, In C.R. Geier, M.B. Barber, G.A. Tolley, C. Nash, T.R. Whyte, and

J. Herbstritt (Organizers). Upland Archeology in the East, Symposium No. 3. USDA

Forest Service-Southern Region and Archeological Society of Virginia, Richmond,

VA. Spec. Publ. No. 38-Part 3.

Watson, P.J. 2001. Ridges, rises, and rocks; caves, coves, terraces, and hollows: Appalachian

archaeology at the millennium. Pp. 319–322, In L.P. Sullivan and S.C. Prezzano

(Eds.). Archaeology of the Appalachian Highlands. University of Tennessee Press,

Knoxville, TN.

Wecker, S.C. 1964. Habitat selection. Scientific American 211(4):109–116.

Wetterer, J.K. 1989. Central-place foraging theory: When load size affects travel time.

Theoretical Population Biology 36:267–280.

Williams, G.C. 1966. Adaptation and Natural Selection: A Critique of Some Current

Evolutionary Thought. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ. 307 pp.

Wilson, E.O. 1975. Sociobiology: The New Synthesis. Harvard University Press, Cambridge,

MA. 697 pp.

Wilson, E.O. 1978. On Human Nature. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA. 260 pp.

Yahner, R.H. 1995. Eastern Deciduous Forest: Ecology and Wildlife Conservation. University

of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis, MN. 220 pp.

The Southeastern Naturalist is a peer-reviewed journal that covers all aspects of natural history within the southeastern United States. We welcome research articles, summary review papers, and observational notes.

The Southeastern Naturalist is a peer-reviewed journal that covers all aspects of natural history within the southeastern United States. We welcome research articles, summary review papers, and observational notes.