2008 SOUTHEASTERN NATURALIST 7(1):173–179

A Complex Mimetic Relationship Between the Central

Newt and Ozark Highlands Leech

Malcolm L. McCallum1,*, Stacy Beharry2, and Stanley E. Trauth3

Abstract - In response to their strikingly similar coloration, we tested for a mimetic

relationship between Notophthalmus viridescens louisianensis (Central Newt) and

Macrobdella diplotertia (Ozark Highlands leech). Early observations took place

in a south-central Missouri woodland pond. Later, feeding experiments involving

ducks, geese, and native fishes were conducted. Our results support a mimetic relationship

between these 2 species that is not a simple classification. More in-depth

study may be needed to elucidate the true nature of this relationship.

Introduction

Three forms of mimicry have been defined. They are aggressive, Mullerian,

and Batesian mimicry. In aggressive (Peckhamian) mimicry, the

mimic uses its conformation to intimidate or attack the model or the model’s

predator (Lloyd 1965). In Batesian mimicry, a palatable prey mimics

a distasteful animal for protection (Bates 1862). The usual example of

this is the viceroy/monarch butterfly mimicry system (Brower 1958), although

we now know this is a false example (Ritland and Brower 1991).

Müllerian mimicry involves a system of species that may or may not

be taxonomically related but share similar warning colors or behaviors

(Muller 1878). The striped pattern of many bees is a classic example of

such a system. We investigated a potential mimetic relationship between

Macrobdella diplotertia Meyer (Ozark Highlands Leech) and Notophthalmus

viridescens louisianensis (Wolterstorff) (Central Newt).

Despite the importance of gathering natural history information on all

species (Bury 2006, Fitch 2006, McCallum and McCallum 2006, Trauth

2006), we know little about the life history of the Ozark Highlands Leech.

Its documented range includes several counties in Arkansas, two counties

in Missouri (Trauth and Neal 2004), and 3 counties in Kansas (Tuberville

and Briggler 2003). Studies conducted on the foraging habits of the

Ozark Highlands Leech suggest that this species is an amphibian-egg

predator (Trauth and Neal 2004) and a predacious sanguivore (Tuberville

and Briggler 2003). There is, however, little known about the palatability

of Ozark Highlands Leech to potential predators.

1Biological Sciences Program, Texas A&M University-Texarkana, 2600 Robison

Road, Texarkana, TX 75501. 2Department of Biology, Morgan State University, 1700

East Coldspring Lane, Baltimore, MD 21251. 3Department of Biological Sciences,

Arkansas State University, PO Box 599, State University, AR 72467. *Corresponding

author - Malcolm.mccallum@tamut.edu.

174 Southeastern Naturalist Vol.7, No. 1

The Central Newt is a small salamander occurring in the eastern half of

North America. This animal has a unique life cycle in that eggs hatch into

larvae that grow to about 3 cm, then emerge from the water as aposematically

colored efts. They live a terrestrial existence for 6 months to 5 years, then return

to the water as aquatic adults (Trauth et al. 2004). All life stages produce

tetrodotoxin, a potent poison (Formanowicz and Brodie 1982), and are avoided

by many predators (Brandon et al. 1979, Brodie 1968, Brodie and Howard

1972). Despite this general aversion by predators, Central Newts can be taken

as food by various species of reptiles and other organisms (McCallum 2001).

This study follows on observations of Ozark Highlands Leech and Central

Newts in a fishless pond located in the Owls Bend area in the Ozark

National Scenic Riverways of the Ozark Plateau (Shannon County, MO).

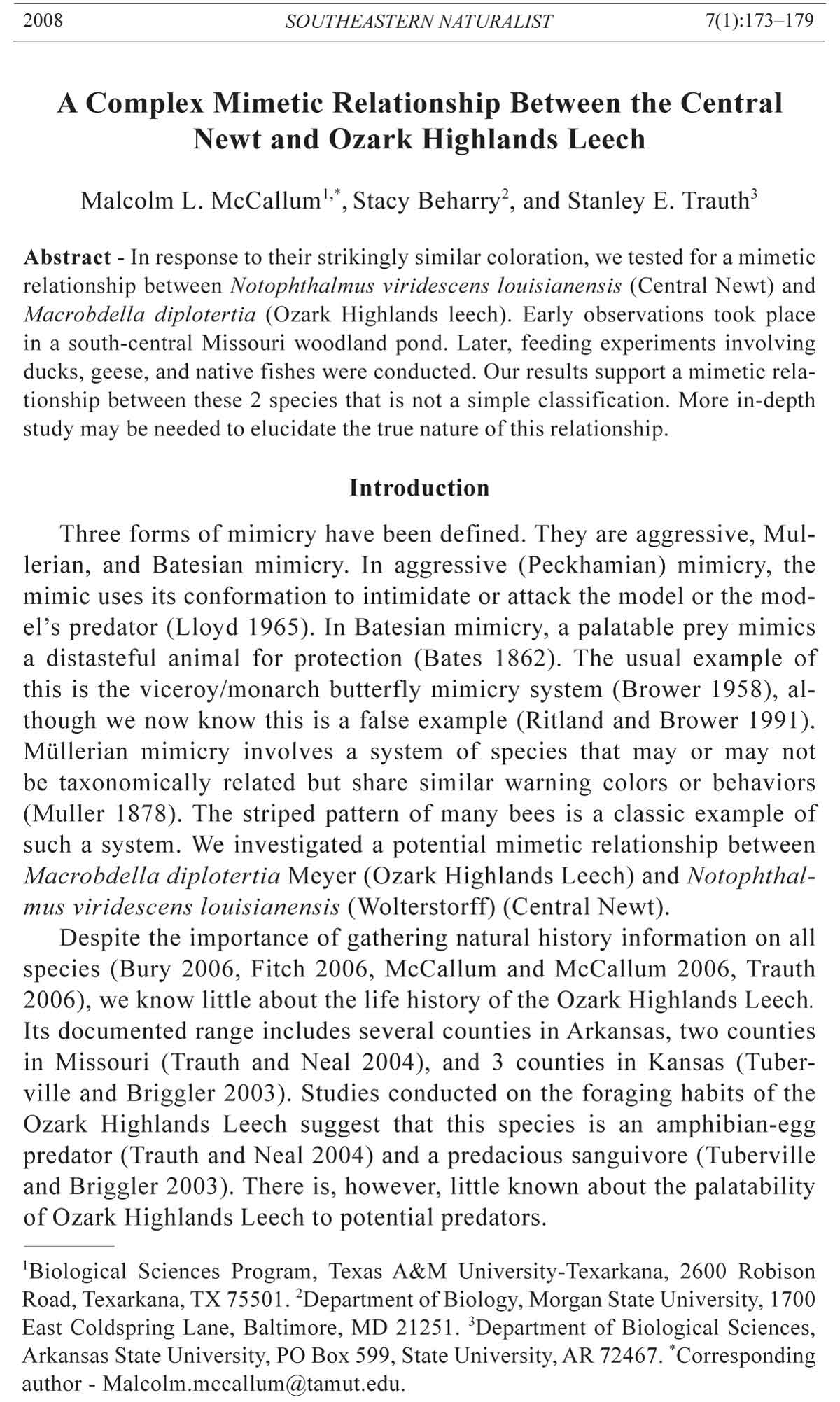

We observed similarities in the coloration (Fig. 1) and swimming behavior

of these two species. Both species share speckled patterns of black spots on

their ventrum and dorso-laterally positioned rows of red spots. The dorsal

background coloration in both species is olive-green. The ventrum of both

species is yellow to cream colored. Ozark Highlands Leeches and Central

Newts also swim in a similar undulating fashion.

The similarities between the Central Newt and Ozark Highlands Leech

suggested a mimetic complex. Herein, we test for the presence of mimicry

between these two species, and identify what kind of mimicry is exhibited. If

potential predators find 1 of these 2 species palatable, but not the other, this

Figure 1. Comparison of lateral (top two photos) and ventral (lower two photos) spotting

pattern between Notophthalmus viridescens louisianensis (Central Newt) and

Macrodbella diplotertia (Ozark Highlands Leech).

2008 M.L. McCallum, S. Beharry, And S.E. Trauth 175

would suggest Batesian mimicry. If neither species is found to be palatable,

the results would suggest Müllerian mimicry. Finally, if one species mimics

the other to obtain food or partake in other kinds of aggression, the results

would favor aggressive mimicry.

Materials and Methods

Avian predation

Palatability of Ozark Highlands Leech and Central Newt were examined

by offering them to free-ranging resident Anas platyrhynchos L. (Peking

and Mallard Ducks), Anser cygnoides (Swan Goose), and Branta canadensis

L. (Canada Geese) housed at Craighead Forest Park (Craighead County),

Jonesboro, AR. These species were chosen based on the observation that

Peking Ducks and Chinese Geese will eat other leeches (species unknown)

and earthworms (M.L. McCallum, pers. observ.).

We conducted 3 feeding trials, each time using a randomly selected

member of the fl ock (n = 8). All waterfowl were believed to be naïve to

Central Newts and Ozark Highland Leeches because neither species has

been observed at Craighead Forest Park since at least 1983. Each bird was

presented an Ozark Highlands Leech, Central Newt, or Lumbricus terrestris

(nightcrawler) on the initial offering, and the feeding response was recorded.

Thereafter, individual birds were offered a modified randomized selection of

either Ozark Highlands Leech or Central Newt so that no prey species was

offered 3 times in succession (Fig. 2).

The acceptability of each prey type was also tested using a captive fl ock

of Anas platyrhynchos ducklings. Five trials were conducted with each of

2 male and 3 female ducks. These ducks were naïve to both potential prey

species, and were not fed for 24 hr prior to the experiment. In each trial, three

of each prey type were placed in a 1.2 x 1.2 m plastic wading pool filled with

water. Each duckling was chosen at random and allowed to forage in the pool

for 30 min. The survivorship of prey was observed and scored as follows:

1) eaten, 2) pecked only, or 3) killed but not eaten. The data were analyzed

via decision theory using chi-square (α = 0.05).

Figure 2. Experimental design for presentation of prey to avian predators.

176 Southeastern Naturalist Vol.7, No. 1

Fish predation

In our third experiment, we tested the acceptability of these prey to 3

Lepomis cyanellus Rafinesque (Green Sunfish; mean mass = 104 g, mean

body length = 175 mm) and 3 Micropterus salmoides Lacépede (Largemouth

Bass; mean =156 g, mean body length = 180 mm). Fish were collected from

a private pond in Jonesboro, AR, where neither of our proposed mimics occurred.

Green Sunfish and Largemouth Bass were communally housed in a

120-L aquarium prior to experimentation. They were transferred separately

to a 200-L aquarium where fish were individually tested. In each trial, a

single fish was placed in the test aquarium along with three specimens of

each prey type. Observations were made every three hours during the first

12 hr of the study, and then again at the end of the 24 hr period. Results were

tabulated (as eaten or killed but not eaten) and analyzed via decision theory

with chi-square (α = 0.05).

Results

Avian predation

Feral ducks and geese found both Ozark Highlands Leeches and Central

Newts unpalatable. These waterfowl refused to eat Ozark Highlands Leech

(0/8, 0% eaten). Similarly, no newts were consumed. Nightcrawlers were

largely palatable. Seven of the 8 nightcrawlers offered were consumed.

Ducklings found both Ozark Highlands Leeches and Central Newts unpalatable.

Of the 15 Ozark Highlands Leeches presented, none was consumed,

whereas 1 of the 15 Central Newt was eaten. Conversely, 12 of 15

nightcrawlers were eaten. A single duckling refused all prey items offered.

Results of these trials are provided in Table 1. Ducks would peck at a leech

when it swam by, but would quickly release it. After a short period, some

ducks would attack again. Ducks tried to eat newts on their first introduction.

There were no statistical differences between individual birds in response to

Central Newt (χ2 = 4.0, df = 4, P > 0.25), Ozark Highlands Leech (χ2 = 4.0,

df = 4, P = 1), or nightcrawler (χ2 = 4.0, df = 4, P = 1).

Fish predation

Sunfish refused to eat Ozark Highlands Leeches and Central Newts. Of

the 9 nightcrawlers presented, only 1 was consumed (Table 2). During each

trial, Ozark Highlands Leeches constantly attached themselves to the fish.

They then remained attached until the fish were able to remove it by hitting

Table 1. Responses of the five ducks to each prey type (n = 15). E = number eaten; K = killed,

but not eaten; P = pecked only (attacked); and % S = percent survivorship.

Prey Item P-value E K P % S

Lumbricus terrestris (nightcrawler) 0.97 12 0 0 20.0

Notophthalmus viridescens louisianensis (Central Newt) 0.03 1 3 13 73.3

Macrobdella diplotertia (Ozark Highlands Leech) 0.00 0 0 36 100.0

2008 M.L. McCallum, S. Beharry, And S.E. Trauth 177

on the side of the container. Each fish was attacked several times over the

24 hr period. However, there were no visible wounds on the fish and they

appeared to be uninjured.

Largemouth Bass refused to eat all Central Newts or Ozark

Highlands Leeches, whereas 6 of 9 nightcrawlers were consumed.

Ozark Highlands Leeches attacked Largemouth Bass as described earlier

with Sunfish. During the second trial, 2 bass died, presumably from attacks by

leeches. These fish were found with Ozark Highlands Leeches attached to and

feeding on the gills. Ozark Highlands Leeches migrated from the opercular

region into the mouth and appeared to be feeding on the fish from within the

pharyngeal region. These fish were examined and found to have wounds in

the pharynx and opercular sinuses.

Discussion

Avian predation: evidence for Müllerian mimicry?

Both Central Newts and Ozark Highlands Leeches were rejected

as food by all species. Of the 8 Ozark Highlands Leeches offered, none was

accepted as food by feral ducks or geese. At present, it is unknown if secretions

of Ozark Highlands Leech are noxious or toxic; however, the leeches

were rejected at nearly equal rates as were the Central Newts, suggesting

neither was palatable and providing limited evidence that a Müllerian complex

might exist.

There were higher acceptance rates and lower survivorship for Central

Newts with juvenile ducks than with adult feral ducks. Of the newts offered

to the juvenile ducks, 73.3% were rejected, whereas there was a 100% rejection

rate by adult ducks. This may reflect the naïveté of the juveniles.

Juveniles were less than 3 months old and were conditioned to captivity.

Whenever they were previously fed by humans, they received palatable

items. This preconditioning might have confounded the results because

these ducks could have learned that food offered by humans is always

palatable. The feral ducks undoubtedly encountered many noxious items

in their lives and learned to test unfamiliar foods before eating them. This

comparison of two extremes in avian experience regarding human food

offerings strengthens the rejection results, reinforcing that both of these

species are quite unacceptable to waterfowl.

Table 2. Response of each fish predator to each prey type. E = eaten, and % S = percent survivorship.

Largemouth Bass Sunfish

Prey Item % S E % S E

Macrobdella diplotertia (Ozark Highlands Leech) 100.0 0 100.0 0

Notophthalmus viridescens louisianensis (Central Newt) 100.0 0 100.0 0

Lumbricus terrestris (nightcrawler) 33.3 6 88.9 1

178 Southeastern Naturalist Vol.7, No. 1

Fish predation

Except with Green Sunfish, Nightcrawlers were acceptable food types,

but both Central Newts and Ozark Highlands Leeches were rejected by

fish. The fish however, were found quite palatable by Ozark Highlands

Leeches. This result suggests aggressive mimicry might occur with fish.

Studies conducted by Tuberville and Briggler (2003) indicate that these

leeches are sanguivorous, yet no information on host preference has been

given. In their native habitat, Central Newts can be found swimming about

among sunfish unharmed (M.L. McCallum, pers. observ.; R. Brandon,

Southern Illinois University, Carbondale, IL, pers. comm.). If fish learned

that Central Newts were noxious, they might also have learned that this

species doesn’t present a threat. In this case, fish might ignore the leeches

due to the swimming behavior and color pattern they share in common with

Central Newt. This behavior would allow Ozark Highlands Leeches to approach

closer to fish than normally possible, providing a better opportunity

to prey upon the fish in this study. Additionally, both species were from the

same pond. Further investigations are needed to elucidate community effects

on Central Newt’s role as a Batesian mimic of this leech.

The function of these schemes requires that predators can and do interpret

signals from both organisms in the same way. These 2 unrelated species

demonstrate similar swimming behavior, coloration, and patterning. These

results demonstrate the confusing behavioral patterns, suggesting a highly

complex relationship. Other investigators have identified equally confusing

systems of mimicry that cannot easily be classified (Brower 1958), and

some speculate that all mimicry may lie somewhere along a spectrum (Vane-

Wright 1991). It is clear that the relationship we have identified between

these distinctly different species could provide an interesting model for

future research to elucidate our understanding of this simple but confusing

evolutionary system.

Acknowledgments

We thank Bill Moser (Smithsonian Institution) for verifying the species of leech.

Literature Cited

Bates, H.W. 1862. Contributions to an insect fauna of the Amazon valley. Transactions

of the Linnean Society of London 23:495–566.

Brandon, R.A., G.M. Labanick, and J.E. Huheey. 1979. Learned avoidance of Brown

Efts Notophthalmus viridescens louisianensis (Amphibia, Urodela, Salamandridae).

Journal of Herpetology 13:171–176

Brodie, E.D., Jr. 1968. Investigations of the skin toxins of the Red-spotted Newt, Notophthalmus

viridescens viridescens. American Midland Naturalist 80:276–280.

Brodie, E.D., Jr., and R.R. Howard.1972. Behavioral mimicry in the defensive displays

of the urodele amphibians Notophthalmus viridescens and Pseudotriton

ruber. BioScience 22:666–667.

2008 M.L. McCallum, S. Beharry, And S.E. Trauth 179

Brower, J.V. 1958. Experimental studies of mimicry in some North American butterfl

ies. Evolution 35:32–47.

Bury, R.B. 2006. Natural history, field ecology, conservation biology, and wildlife

management: Time to connect the dots. Herpetological Conservation and Biology

1:56–61.

Fitch, H.S. 2006. Ecological succession on a natural area in northeastern Kansas

from 1948 to 2006. Herpetological Conservation and Biology 1:1–5.

Formanowicz, D.R., Jr., and E.D. Brodie, Jr. 1982. Relative palatabilities of members

of a larval amphibian community. Copeia 1982:91–97.

Lloyd, J.E. 1965. Aggressive mimicry in Photuris: Firefl y femmes fatales. Science

149:653–654.

McCallum, M.L. 2001. The unken refl ex in the Eft (Notophthalmus viridescens):

Warning for predators, or escape maneuver? Bulletin of the Maryland Herpetological

Society 37:101–114.

McCallum, M.L., and J.L. McCallum. 2006. Publication trends of natural history and

field studies in herpetology. Herpetological Conservation and Biology 1:62–67.

Muller, F. 1878. Ituna and Thyridia: A remarkable case of mimicry in butterfl ies.

Proceedings of the Entomological Society of London 1879:20–29.

Ritland, D., and L. Brower. 1991. The viceroy butterfl y is not a batesian mimic.

Nature 350:497–498.

Trauth, S.E. 2006. A personal glimpse into natural history and a revisit of a classic

paper by Fred R. Cagle. Herpetological Conservation and Biology 1(1):68–70.

Trauth, S.E., and R.G. Neal. 2004. Feeding response by the leech Macrobdella

diplotertia (Annelida: Hirudinea) to Wood Frog and Spotted Salamander egg

masses. Journal of the Arkansas Academy of Science 58:139–141.

Trauth, S.E., H.W. Robison, and M.V. Plummer. 2004. The Amphibians and Reptiles

of Arkansas. University of Arkansas Press, Fayetteville, AR. 421 pp.

Turberville, J.M., and J.T. Briggler. 2003. The occurrence of Macrobdella diplotertia

(Annelida: Hirudinea) in the Ozarks Highlands of Arkansas and preliminary observations

on its feeding habits. Journal of Freshwater Ecology 18:155–159.

Vane-Wright, R.I. 1991. A case of self deception. Nature 350:460–461.

The Southeastern Naturalist is a peer-reviewed journal that covers all aspects of natural history within the southeastern United States. We welcome research articles, summary review papers, and observational notes.

The Southeastern Naturalist is a peer-reviewed journal that covers all aspects of natural history within the southeastern United States. We welcome research articles, summary review papers, and observational notes.