2014 Northeastern Naturalist Notes Vol. 21, No. 1

N8

J.S. Kellam

Rare Extra-pair Copulation in Downy Woodpeckers

James S. Kellam*

Abstract - Extra-pair copulation (EPC) behavior is widespread among birds in general, but rarely

has been documented among members of the Woodpecker family. Here I report on an EPC observed

between a nesting female Picoides pubescens (Downy Woodpecker) and a neighboring male for

whom no nest was found. Behavioral observations aided by radio telemetry showed that the female

had interacted with both her nesting partner and the extra-pair male on a regular basis in preceding

months. This is only the second published account of an EPC in this species within the last 50 years.

The circumstances and rarity of the behavior as shown by woodpeckers may lead to a better understanding

of its evolutionary function among birds.

A wide variety of socially monogamous birds can have young in their nests unrelated to

at least one parent (Birkhead and Møller 1996). The frequency of such extra-pair copulation

(EPC) and the prevalence of resulting offspring vary across avian taxonomic orders

and also seems to correlate to the degree of male parental care (Birkhead and Møller 1996,

Griffith et al. 2002, Matysioková and Remeš 2012). The incidence of extra-pair young is

lower among species that have relatively high degrees of paternal care, possibly because

females risk losing paternal care by accepting EPCs (Griffith et al. 2002).

Based on this evolutionary pattern, the Woodpecker family (Picidae) would be predicted

to show low rates of EPC because woodpecker species show high levels of paternal care

relative to other kinds of birds (Winkler et al. 1995). Paternal care in woodpeckers includes

aid in nest construction, nest defense, incubation (including overnight), nest sanitation, and

delivery of food to young. There are no data on the rates of EPC among woodpeckers, but

limited data collected on extra-pair young found in woodpecker nests has been consistent

with predictions. Rates of extra-pair paternity in socially monogamous woodpeckers range

from 0% in Dendrocopus medius L. (Middle Spotted Woodpecker) and D. major L. (Great

Spotted Woodpecker) (Michalek and Winkler 2001) to 2.5% and 5.5% of young in two

studies on Picoides tridactylus L. (Three-toed Woodpecker), respectively (Li et al. 2009,

Pachacek et al. 2005). In cooperatively breeding species, Melanerpes formicivorus (Swainson)

(Acorn Woodpecker) showed no extra-pair or extra-group fertilizations (Haydock et al.

2001), and P. borealis (Vieillot) (Red-cockaded Woodpecker) had a 1.3% rate of extra-pair

paternity (Haig et al. 1994). The average rate of extra-pair paternity in all birds is around

11% of young (Griffith et al. 2002). Woodpecker species are thus well below average in

this metric. However, the 5 species of woodpecker reported above represent only a small

fraction of the 200-member Picidae family. Therefore, observations on other species in

this group are needed to determine whether the Picidae family as a whole conforms to the

hypothesized pattern of the evolution of extra-pair behavior in birds. In this note, I describe

the occurrence of an EPC in P. pubescens L. (Downy Woodpecker) for only the second

time in the published literature. The first observed EPC in this species was documented by

Lawrence (1967) and occurred sometime in the 1950s. She reported the incident without

providing much detail. While I cannot confirm that the copulation I observed successfully

resulted in fertilization, the observation indicates that some level of polyandry is possible

in Downy Woodpeckers.

*Department of Biology, Saint Vincent College, 300 Fraser Purchase Road, Latrobe, PA 15650; james.

kellam@stvincent.edu.

Manuscript Editor: Jean-Pierre L. Savard

Notes of the Northeastern Naturalist, Issue 21/1, 2014

N9

2014 Northeastern Naturalist Notes Vol. 21, No. 1

J.S. Kellam

The EPC I observed involved woodpeckers that were individually marked with colored

leg bands as part of a larger study investigating pair-bond maintenance behavior of 140

individuals during non-breeding periods from 1998–2002 (Kellam et al. 2004). The 60-ha

forested study site was located in and around the Ross Biological Reserve (Purdue University),

a strip of hilly land between the Wabash River and a public golf course in Tippecanoe

County, IN. The study protocols included tracking the locations of each woodpecker and

documenting the identity of conspecifics located near each woodpecker (if any). Most data

were collected while woodpeckers wore radio transmitters via a leg loop harness. Female

“GMGM” was first captured in a trap baited with suet on 27 February 1999. I waited at least

a month before attaching transmitters to newly captured woodpeckers to better ensure they

were residents. I attached a transmitter to GMGM on 24 March. Male “RPRP” was first

captured and banded on 20 January and was given a radio transmitter on 30 March. Male

“GRGR” was first captured and banded on 14 January .

Pre-breeding season behavioral observations on the three woodpeckers showed that

female GMGM was seen in March once with GRGR male (distance = 40 m), twice with

RPRP male (average distance = 22 m), and two other times with no other male within

50 m. In April, GMGM female was seen three times with GRGR male (average distance

= 9 m), three times with RPRP male (average distance = 25 m), and once with no other

male within 50 m. In sum, GMGM female was seen more often with RPRP male than

with any other male during the 2-month period, but her inter-individual distances with

GRGR male became smaller as the breeding season approached. The female was not

observed with any other males in the population even though at least 5 others used home

ranges adjacent to hers.

Female GMGM and male GRGR established a nest in early May 1999. The pair was

found at a freshly excavated nest hole on 05 May at a location within the home ranges of

both birds (Fig. 1). I monitored the nest every few days through May and into June. Ultimately,

the pair cared for young in this nest, which fledged on 14 June. Since the Downy

Woodpecker nestling period ranges from 18 to 21 days (Jackson and Ouellet 2002), eggs

likely hatched at this nest sometime during 25–28 May. Counting back another 12 days to

account for the species’ incubation period (Jackson and Ouellet 2002), the clutch at this

nest should have been completed somtime during 14–17 May. I believe 17 May is the better

estimate because I was able to capture GMGM female on 19 May and I observed on

her a well-developed and smooth brood patch, but it was not as highly vascularized as that

of 7 other woodpeckers I had captured during the same time frame in previous years. This

observation indicates that incubation had only just begun for GMGM female (e.g., Redfern

2010).

Written field notes indicate that on the overcast morning of 15 May 1999, I checked on

the status of the GMGM/GRGR nest and detected no activity there over the course of 16

min. I moved on, heading in a direction of a whinny call I had heard while watching the

nest. I found GMGM female 240 m east of the nest at approximately 0830 EST. Then I

heard a sharp “whinny” call behind me. The call was given by RPRP male. GMGM female

flew to his position on a horizontal branch and following a “hover approach” in which the

male left the branch and hovered over the female (cf. Kilham 1974), they copulated for 5

sec. The duration of coition was less than the 10–16 sec duration reported specifically for

Downy Woodpeckers by Kilham (1974) and the 6–16 sec duration reported for woodpeckers

in general (Winkler et al. 1995). The EPC observed between GMGM female and RPRP

male likely took place toward the end of the egg-laying period given a nest fledge date of

14 June. This timing is interesting because the eggs with extra-pair paternity are usually laid

2014 Northeastern Naturalist Notes Vol. 21, No. 1

N10

J.S. Kellam

in the beginning of the egg-laying period in species exhibiting EPC (Vedder et al. 2012).

Earlier EPC may result in a better fertilization rate due to there being more eggs available

(Birkhead 1998).

A freshly excavated tree cavity was located within view of the copulation site, and

since copulations are usually reported as taking place near a nest (Kilham 1974), I monitored

this cavity for several weeks to see if this was the nest site of RPRP male. However,

no nesting activity was observed at this cavity. I found 6 nests within the study site in

1999, but I never observed male RPRP tending a nest. He stopped frequenting the study

site after 19 May when he was last spotted at a baited trap. He was detected three more

times in the following year.

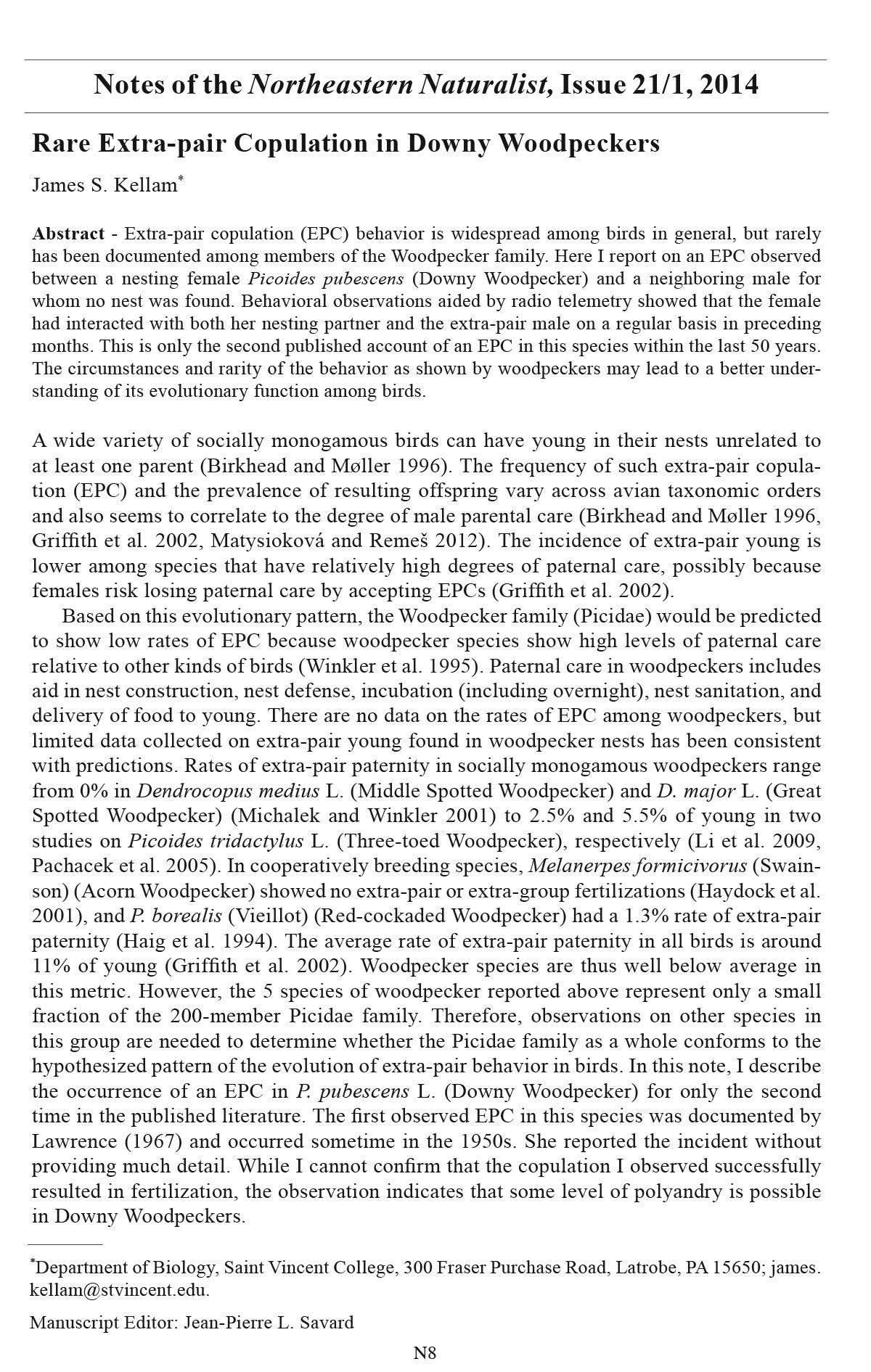

Figure 1. Home ranges of a nesting pair of Downy Woodpeckers, GRGR male and GMGM female.

The home range of RPRP male is also shown, along with the location of the extra-pair copulation

between RPRP male and GMGM female. Home ranges were drawn using a fixed kernel estimator

(Hooge and Eichenlaub 1997) representing the 75% core-use area, which excludes areas not used

regularly by the woodpeckers. GMGM and RPRP ranges are drawn from 20 positions per bird from

13 February–19 April 1999, mostly collected when they were wearing radio transmitters starting in

late March. GRGR male was not wearing a radio transmitter; his range is drawn from 11 positions

gathered opportunistically from 14 January–16 June. Observations of woodpeckers at baited traps

within the study site were excluded from home-range analysis to reduce bias.

N11

2014 Northeastern Naturalist Notes Vol. 21, No. 1

J.S. Kellam

The location where the extra-pair copulation took place was at the edge of home ranges

occupied by GMGM female and RPRP male (Fig. 1). This is unusual for within-pair copulations,

but may be common behavior for individuals seeking EPC (Lawrence 1967, Westneat

and Stewart 2003). That the EPC took place at the edge of the birds’ respective home ranges

may imply that both male and female were seeking an EPC (Pedersen et al. 2006), rather

than it being sought by only one sex. Both males and females may benefit from extra-pair

behavior, and their separate evolutionary perspectives are rarely considered together (Pedersen

et al. 2006, Westneat and Stewart 2003).

When Lawrence (1967:60) observed the first EPC in Downy Woodpeckers, she noted

that “such incidents are apparently very rare among the woodpeckers”. However, she was

writing well before the advent of the genetic analysis techniques that showed that extra-pair

sexual behavior was common among a wide variety of bird species. Thus, the observation

of an EPC in a woodpecker species appears to be very rare indeed. There is a general lack

of DNA-based parentage data in this taxonomic group. More genetic studies should be performed

in a variety of woodpecker species to help investigators craft a better understanding

as to the functions and outcomes of EPC behavior.

Acknowledgments. Research was funded by Sigma Xi Grants-in-Aid of Research, the

Indiana Academy of Science, and a Frederick N. Andrews Doctoral Fellowship. I thank Dr.

Jeffrey R. Lucas for helpful discussions relating to this work. Procedures relating to the observation,

capture, and radio-tracking of Downy Woodpeckers were approved by the Purdue

University Animal Care and Use Committee under protocols #97-084-2 and #99 -064.

Literature Cited

Birkhead, T.R. 1998. Sperm competition in birds. Reviews of Reproduction 3 :123–129.

Birkhead, T.R., and A.P. Møller. 1996. Monogamy and sperm competition in birds. Pp. 323–343,

In J.M. Black (Ed.). Partnerships in Birds: The Study of Monogamy. Oxford University Press,

Oxford, UK. 420 pp.

Griffith, S.C., I.P.F. Owens, and K.A Thuman. 2002. Extra pair paternity in birds: A review of interspecific

variation and adaptive function. Molecular Ecology 1 1:2195–2212.

Haig, S.M., J.R. Walters, and J.H. Plissner. 1994. Genetic evidence for monogamy in the cooperatively

breeding Red-Cockaded Woodpecker. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 34:295–303.

Haydock, J., W.D. Koenig, and M.T. Stanback. 2001. Shared parentage and incest avoidance in the

cooperatively breeding Acorn Woodpecker. Molecular Ecology 10:1515–1525.

Hooge, P.N., and B. Eichenlaub. 1997. Animal movement extension to ArcView. Version 1.1. United

States Geological Survey. Alaska Biological Science Center, Anchorage, AK.

Jackson, J.A., and H.R. Ouellet. 2002. Downy Woodpecker (Picoides pubescens). No. 613, In A.

Poole (Ed.). The Birds of North America Online, Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY. Available

online at http://bna.birds.cornell.edu.bnaproxy.birds.cornell.edu/bna/species/613. Accessed

27 June 2013.

Kellam, J.S., J.C. Wingfield, and J.R. Lucas. 2004. Nonbreeding season pairing behavior and the

annual cycle of testosterone in male and female Downy Woodpeckers, Picoides pubescens. Hormones

and Behavior 46:703–714.

Kilham, L. 1974. Copulatory behavior of Downy Woodpeckers. Wilson Bulletin 86:23–42.

Lawrence, L. de K. 1967. A comparative life history of four species of woodpeckers. Ornithological

Monographs 5:1–156.

Li, M.-H., K. Välimäki, M. Piha, T. Pakkala, and J. Merilä. 2009. Extrapair paternity and maternity

in the Three-toed Woodpecker, Picoides tridactylus: Insights from microsatellite-based parentage

analysis. PLoS ONE 4(11):e7895.

Matysioková, B., and V. Remeš. 2012. Faithful females receive more help: The extent of male parental

care during incubation in relation to extra-pair paternity in songbirds. Journal of Evolutionary

Biology 26:155–162.

2014 Northeastern Naturalist Notes Vol. 21, No. 1

N12

J.S. Kellam

Michalek, K.G., and H. Winkler. 2001. Parental care and parentage in monogamous Great Spotted

Woodpeckers (Picoides major) and Middle Spotted Woodpeckers (Picoides medius). Behaviour

138:1259–1285.

Pechacek, P., K.G. Michalek, H. Winkler, and D. Blomqvist. 2005. Monogamy with exceptions:

Social and genetic mating system in a bird species with high paternal investment. Behaviour

142:1099–1120.

Pedersen, M.C., P.O. Dunn, and L.A. Whittingham. 2006. Extraterritorial forays are related to a male

ornamental trait in the Common Yellowthroat. Animal Behaviour 72:479–486.

Redfern, C.P.F. 2010. Brood-patch development and female body mass in passerines. Ringing and

Migration 25:33–41.

Vedder, O., M.J.L. Magrath, D.L. Niehoff, M. van der Velde, and J. Komdeur. 2012. Declining extrapair

paternity with laying order associated with initial incubation behavior, but independent of

final clutch size in the Blue Tit. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 66:603–612.

Westneat, D.F., and I.R.K. Stewart. 2003. Extra-pair paternity in birds: Causes, correlates, and conflict.

Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics 34:365–396.

Winkler, H., D.A. Christie, and D. Nurney. 1995. Woodpeckers: An Identification Guide to the Woodpeckers

of the World. Houghton Mifflin Company, New York, NY. 406 pp.