The Distribution of Ocypode quadrata, Atlantic Ghost Crab

(Decapoda: Brachyura: Ocypodidae) Megalopae, beyond the

Presumptive Northern Boundary of Adult Populations in the

Northwest Atlantic

John J. McDermott

Northeastern Naturalist, Volume 20, Issue 4 (2013): 578–586

Full-text pdf (Accessible only to subscribers. To subscribe click here.)

Access Journal Content

Open access browsing of table of contents and abstract pages. Full text pdfs available for download for subscribers.

Current Issue: Vol. 30 (3)

Check out NENA's latest Monograph:

Monograph 22

578

J.J. McDermott

22001133 NORTNHorEthAeSaTsEteRrNn NNaAtTuUraRliAstLIST 2V0(o4l). :2507,8 N–5o8. 64

The Distribution of Ocypode quadrata, Atlantic Ghost Crab

(Decapoda: Brachyura: Ocypodidae) Megalopae, beyond the

Presumptive Northern Boundary of Adult Populations in the

Northwest Atlantic

John J. McDermott*

Abstract - Previous observations on the occurrence of the megalopae of Ocypode quadrata

(Atlantic Ghost Crab) along the inshore waters of the northeastern coast of the US from

New Jersey to southern Massachusetts and the offshore waters of southwestern Nova

Scotia, dating back to the end of the 19th century to recent findings in the 21st century, are

reviewed. Although megalopae were found for the first time north of Cape Cod in plankton

samples from Nova Scotia (1977–1978), they are reported here for the first time on beaches

north of Cape Cod along the east coast of Massachusetts and as far north as Kennebunkport,

ME. The nearest populations of adult Atlantic Ghost Crabs are located along the southeast

coast of Massachusetts. Thus, zoeae larvae and megalopae originating below Cape Cod

must migrate northward around the Cape or via Buzzards Bay through the Cape Cod Canal.

Likewise, megalopae reported from southwestern Nova Scotian waters must have originated

from adult populations to the south. The incidence of megalopae from New Jersey

northward along the coast suggests a recruitment period from late summer into early fall for

Atlantic Ghost Crabs on the northern edge of their range.

Introduction

Ocypode quadrata (Fabricius) (Atlantic Ghost Crab) inhabits burrows on sandy

beaches from Block Island, RI to Santa Catarina, Brazil, and the species has also

been reported from the islands of Bermuda and the Fernando de Noronha archipelago,

Brazil (Williams 1984). Atlantic Ghost Crabs populate beaches of the islands

of Martha’s Vineyard, Nantucket, Muskeget, and Tuckermuck off the southeast

coast of Massachusetts, and Monomoy and Chatham at the elbow of Cape Cod (L.

Johnson, Biodiversity Works, Edgartown, MA and T. Simmons, Natural Heritage

and Endangered Species Program, West Boylston, MA, pers. comm.). Simmons

first recorded crabs at some of the above-mentioned locations beginning in 1985,

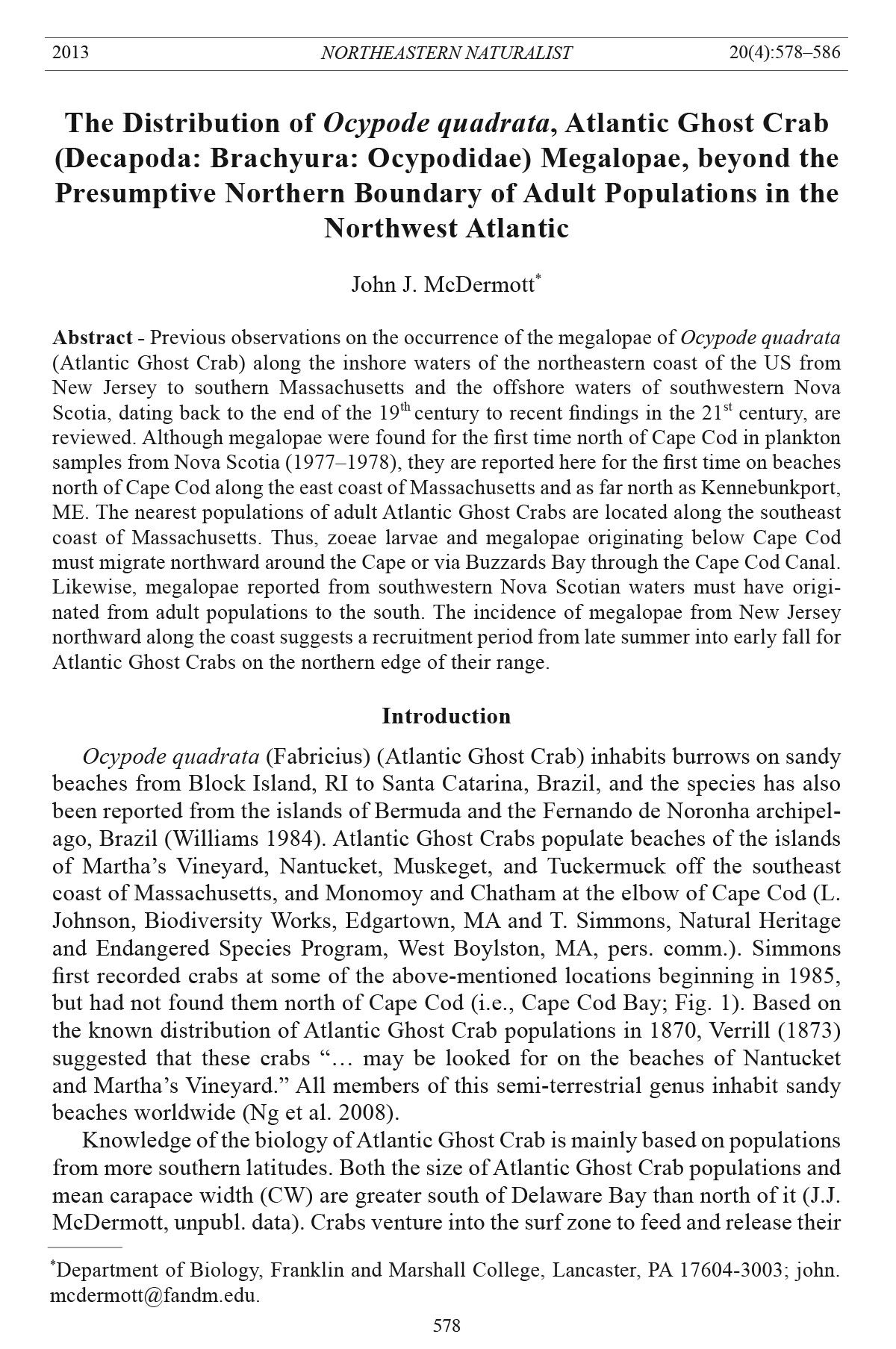

but had not found them north of Cape Cod (i.e., Cape Cod Bay; Fig. 1). Based on

the known distribution of Atlantic Ghost Crab populations in 1870, Verrill (1873)

suggested that these crabs “… may be looked for on the beaches of Nantucket

and Martha’s Vineyard.” All members of this semi-terrestrial genus inhabit sandy

beaches worldwide (Ng et al. 2008).

Knowledge of the biology of Atlantic Ghost Crab is mainly based on populations

from more southern latitudes. Both the size of Atlantic Ghost Crab populations and

mean carapace width (CW) are greater south of Delaware Bay than north of it (J.J.

McDermott, unpubl. data). Crabs venture into the surf zone to feed and release their

*Department of Biology, Franklin and Marshall College, Lancaster, PA 17604-3003; john.

mcdermott@fandm.edu.

Northeastern Naturalist Vol. 20, No. 4

J.J. McDermott

2013

579

first zoeae during the reproductive period. They scavenge beach wrack; feed on a

great diversity of aquatic sympatric invertebrates (e.g., mollusks and crustaceans)

(Wolcott 1978); consume vertebrates, such as shore bird and turtle hatchlings (Knott

2005, Williams 1984); and they deposit-feed at times (Robertson and Pfeiffer 1982).

In New Jersey, crabs probably become ovigerous in late spring or early summer,

and some females still carry broods in July (Milne and Milne 1946). Farther south,

in North Carolina, Atlantic Ghost Crabs are ovigerous from approximately April to

July (Williams 1984), while those along the Texas coast have an extended reproductive

period with two broods, the second of which produces first crab stages in late

October (Haley 1972). Embryos of Atlantic Ghost Crabs are hatched as first zoeae in

the shallow surf of sandy beaches, molt through four more planktonic zoeal stages,

and finally metamorphose into megalopae that return to suitable beaches where they

metamorphose into the first crab stage (Diaz and Costlow 1972).

Measurements of Atlantic Ghost Crabs collected during surf-zone research in

New Jersey in the late 1970s and early 1980s, showed that the largest male and

female crabs were 43.3 mm and 44.2 mm CW, respectively (J. McDermott, unpubl.

data). Milne and Milne (1946) recorded a 48-mm specimen near Townsends Inlet,

just north of Cape May, NJ (sex of crab and number measured were not given). Atlantic

Ghost Crab numbers are small in northeastern New Jersey (e.g., Sandy Hook

at the entrance to New York harbor), but populations become larger from Atlantic

City south to Cape May (Grant 1983, Milne and Milne 1946). T. Simmons (pers.

observ. and unpubl. data) also found that crabs inhabiting the islands of southeastern

Massachusetts are smaller than those he has seen from New Jersey and North Carolina.

Most were less than 30 mm CW, but some reached 41 mm CW. On Delaware

shores, Morris (1957) noted that adults were >45 mm CW (no other data given). Atlantic

Ghost Crabs farther south and into the Gulf of Mexico reach a maximum CW

of >50 mm: e.g., 50 mm in South Carolina (Ruppert and Fox 1988); and male and

female crabs from the Texas coast reach 53.5 mm and 52.0 mm CW, respectively

(Haley 1969).

I recently reviewed the literature regarding Atlantic Ghost Crab megalopae and

reported our current knowledge of their occurrence and distribution in the western

Atlantic, their distinctive morphology and large size, and comparisons with

those of other species within the genus (McDermott 2009). At the time I was unaware

of a survey of brachyuran larvae and megalopae conducted in the offshore

waters of southwestern Nova Scotia in the summers of 1977 and 1978, during

which Atlantic Ghost Crab megalopae were found (Roff et al. 1984). The authors

of the study collected larvae of 35 crab species from 3055 plankton samples, accounting

for 48 of >600,000 specimens. While many aspects of Atlantic Ghost

Crab biology and ecology, as well as of the Ocypodidae in general are known

(Knott 2005, Williams 1984), relatively little information exists on larval distribution

and the occurrence and behavior of megalopae, the most important stage in

the species’ recruitment to sandy beaches.

The purpose of this paper is to present recent information on the occurrence of

Atlantic Ghost Crab megalopae found north of New Jersey and particularly north

580

J.J. McDermott

2013 Northeastern Naturalist Vol. 20, No. 4

of Cape Cod. I also discuss factors that might be involved in a possible range expansion

of this species.

Methods

This study involves a review of previous published data on the occurrence of

Atlantic Ghost Crab megalopae on sandy beaches from New Jersey to Long Island

Sound (McDermott 2009; Smith 1873a, 1873b, 1880; Williams 1984). Data

on Atlantic Ghost Crab megalopae obtained in a survey of brachyuran plankton

from waters off Nova Scotia (Roff et al. 1984) are involved in this review. Finally,

I present recent unpublished data regarding the occurrence of Atlantic

Ghost Crab megalopae from coastal beaches north of Cape Cod, in Massachusetts

and Maine. I examined specimens and/or photographs from these sources,

confirmed identifications, and obtained measurements for comparisons with

megalopae from New Jersey. Carapace width and carapace length (CL) were

measured in millimeters with an ocular micrometer, and I used these values to

calculate the ratio CW/CL.

Results

Atlantic Ghost Crab megalopae have been recorded in very small numbers along

sandy beaches from New Jersey northward to the southern coast of Massachusetts

(Vineyard Sound) (Table 1, Fig. 1). Populations of adult Atlantic Ghost Crabs

inhabit these waters. In the colder waters north of Cape Cod, where adult populations

have not been documented, megalopae of these crabs have been collected on

beaches as far north as Maine during the last few years of this century (Table 1).

Table 1. Seasonal sightings of Ocypode quadrata megalopae from New Jersey to Maine from the 1870s

to 2012. Each date refers to the collection of one specimen except where more than one is indicated.

Location Date Reference

New Jersey (Cape May County 6 Sep 1980 McDermott (2009)

at two locations) 19 Sep 1981

13 Sep 1985

7 Sep 1999

6 Oct 2000

New York (Long Island, south late Aug 1870 Smith (1873a, b)

shore)*

Rhode Island (Block Island)* Aug 1870 Smith (1873a, b)

Massachusetts (Vineyard Sound)* Sep 1875 (early) Smith (1880)

Massachusetts (Gloucester) 26 Aug 2012 O’Connor (pers. comm.)

Massachusetts (Plum Island)** 21 Sep 2012 Hutchings (pers. comm.)

Maine (Kennebunkport) 31 Aug 2010 Kraeuter (pers. comm.)

Maine (Kennebunk) 31 Aug 2012 Miller (pers. comm..)

*= Supposedly numerous, but no exact number given.

**= 2 specimens.

Northeastern Naturalist Vol. 20, No. 4

J.J. McDermott

2013

581

Two megalopae were collected at Sandy Point State Reservation, Plum

Island, MA (information and photos provided by Lisa Hutchings, Education Coordinator,

Joppa Flats Education Center, Newburyport, MA, pers. comm.). One

measured 5.05 mm CW, 6.25 mm CL, CW/CL = 0.81, and although the carapace

of the other crab was damaged, photos and microscopic examination revealed

that it was close to the same size. A single megalopa was collected by William

O’Connor (Gloucester, MA, unpub. data) from Wanson Cove, Gloucester, MA.

Unfortunately the specimen was discarded, but I identified it as an Atlantic Ghost

Crab megalopa from its photograph.

Figure 1. Map showing locations (black circles) where megalopae of Ocypode quadrata

were collected from the 19th to 21st centuries along the northeast coast of the United States

from New Jersey to Maine. Populations of adult crabs are found only south of Cape Cod.

The sites are labeled as follows: CM = Cape May region (two locations, Delaware Bay west

and barrier beaches east on the peninsula); LI = Long Island south shore; BI = Block Island;

VS = Vineyard Sound; G = Gloucester; PI = Plum Island; K = Kennebunk – Kennebunkport

area (two nearby locations). DE = Delaware, RI = Rhode Island.

582

J.J. McDermott

2013 Northeastern Naturalist Vol. 20, No. 4

One megalopa was collected 31August 2010 by John N. Kraeuter (Haskin

Shellfish Research Laboratory, Rutgers University, Port Norris, NJ, pers. comm.)

in sand near the high tide line at Goose Rocks Beach, Kennebunkport, ME (5.85

mm CW, 6.68 mm CL, CW/CL = 0.88). From photographs, I identified a megalopa

collected 31 August 2012 at Parsons Beach, Kennebunk, ME ≈10.4 km south of

Goose Rocks Beach, as Atlantic Ghost Crab (J. Miller, Wells National Estuarine

Research Reserve, Wells, ME, pers. comm.). The crab was released before I could

make measurements. Thus, the megalopae of Atlantic Ghost Crabs have been reported

≈190 km beyond any adult populations (distance measured from the eastern

end of the Cape Cod Canal, MA to Kennebunkport, ME (Fig. 1).

Discussion

Twelve Atlantic Ghost Crab megalopae have been collected from nine locations

on twelve dates from New Jersey to Maine (Table 1). These dates ranged from

late summer to early fall (26 August 2012, in Gloucester, MA to 6 October 2000

at Stone Harbor, NJ). The other ten collections, dating back to the 1870s (Smith

1873a, 1873b, 1880) were in August and September. These data on megalopae,

while very few, suggest a late summer to early fall recruitment period for Atlantic

Ghost Crab in its northernmost range, i.e., New Jersey to Maine. My two decades

of observations of southern New Jersey’s sandy beach surf-zone invertebrate fauna

support this suggestion (McDermott 1983, 1987, 2001, 2005).

Adult Atlantic Ghost Crab populations along the southeast coast of New England

and the islands of Martha’s Vineyard and Nantucket are smaller than those of

southern Long Island and New Jersey, and the latter two populations are considerably

smaller than those on the barrier beaches of the Carolinas (L. Johnson and T.

Simmons , pers. comm.; J. McDermott, pers. observ.).

Cape Cod is recognized as a major barrier to the northern migration of southern

fauna, and the colder water of Cape Cod Bay is thought to prevent northward

movement by some crab species (Smith 1873a, b; Verrill 1873). The Western Gulf

of Maine Coastal Current flows from the northeast into the Bay before branching

and apparently continuing southward offshore of Cape Cod. These topographical

and thermal barriers obviously do not completely impede the migration of Atlantic

Ghost Crab zoeae and megalopae from moving north. Those zoeae and megalopae

that traverse the outer Cape or are carried from Buzzards Bay through the Cape

Cod Canal at the shoulder of Cape Cod might survive long enough to burrow into

a sandy beach, and if competent and tolerant to the colder water, may even molt

into the first crab stage. Warm core eddies off the Gulf Stream may be instrumental

in transporting southern fauna beyond Cape Cod (Lalli and Parsons 1991). At this

point in geological time, however, colder water north of Cape Cod is not conducive

to the establishment of adult populations of Atlantic Ghost Crab. In recent years,

these barriers did not inhibit the establishment of populations of the introduced

Hemigrapsus sanguineus (De Haan) (Asian Shore Crab). First recorded in New

Jersey in 1988, it reached the waters of Maine by 2002 (McDermott 1991, 1998;

Stephensen et al. 2009; Williams and McDermott 1990). This colonization was

Northeastern Naturalist Vol. 20, No. 4

J.J. McDermott

2013

583

predicted from its tolerance to a wide range of water temperatures, as documented

in the in the northwest Pacific (McDermott 1998).

Records for the occurrence of Atlantic Ghost Crab megalopae on Atlantic coastal

beaches of the US are extremely rare, and when megalopae are encountered they

are usually not numerous. Megalopae of the sympatric Indian species of ghost crab,

Ocypode platytarsis H. Milne Edwards and O. cordimanus Latrielle, occurred in

greater numbers on beaches than Atlantic Ghost Crab so that they were sufficient

for laboratory experimentation (Raja Bai Naidu 1954).

The additional carapace measurements and CW/CL ratios presented here from

Atlantic Ghost Crab megalopae collected north of Cape Cod correspond positively

with those recorded previously south of the Cape (McDermott 2009).

Why were Atlantic Ghost Crab megalopae not reported from the surf zone north

of Cape Cod prior to the 21st century? Some might view these recent occurrences

as related to the much-discussed warming trend in the oceans. However, because

planktonic Atlantic Ghost Crab, and other southern brachyuran larvae were collected

in the oceanic waters off southern Nova Scotia (Roff et al. 1984), it is likely

that southern currents and eddies have been bringing larvae and megalopae into

the cold northern waters for centuries. It has been shown here that some of these

megalopae have survived their oceanic journeys and reached sandy beaches along

the coastal United States north of Cape Cod. The occurrence of the Atlantic Ghost

Crab megalopae on sandy beaches continues to be enigmatic, as I indicated in my

scattered observations along the New Jersey coast (McDermott 2009).

In order to understand the role of Atlantic Ghost Crab megalopae in recruitment,

a concerted effort is needed to explore sandy beaches more intensively and sample

quantitatively for megalopae and the first few crab instars, especially during the

suggested late summer and early fall recruitment period in northern waters. Studies

of ghost crab populations have not emphasized this period in the recruitment of

ghost crabs to sandy beaches. Plankton should be sampled for the zoeal stages in the

life cycle as well as megalopae (Diaz and Costlow 1972, Roff et al. 1984) in conjunction

with exploration for burrowed megalopae in the intertidal zone. Tide stage

may be a factor in avoiding predation in that the incoming tide period would land

the emerging megalopae nearer the upper beach in preparation for metamorphosis.

To my knowledge, all recoveries of megalopae have been in daylight with meager

results. Perhaps megalopae tend to invade beaches in greater numbers in the dark,

which would be a potential adaptation for avoiding visual predators. Lunar phases

could be influencing beach invasions. Addition of information to what little is

known of megalopal behavior and strategy at the time megalopae land and explore

a sandy beach may provide insight into the factors that influence the success or

failure of recruitment (McDermott 2009, Raja Bai Naidu 1994). In addition, results

from laboratory studies focused on megalopal behavioral reactions and tolerances

to temperature fluctuations should relate to their overall survival in the northern

part of their range.

Obviously ghost crab megalopae are continually replenishing the sandy beaches

of the western Atlantic. John Cushing (Vienna, VA, pers. comm., 2012) reported

584

J.J. McDermott

2013 Northeastern Naturalist Vol. 20, No. 4

finding megalopae, “blueberry crabs”, in August for the last 5 years on the beaches

of Duck, NC. He noted that when megalopae “tuck in their legs and tail they look

like a little blueberry or a small blue pebble.” Crane (1940) described and illustrated

from preserved specimens how the megalopa becomes semispherical and

compact as its legs are folded into lateral grooves on the carapace and the abdomen

is flattened against the sternum (see McDermott 2009). Cushing observed that

megalopae “are hard to find” with only a few of them collected each summer. It is

not obvious, therefore, how and when to collect “blueberry crabs” in abundance for

experimental study.

Acknowledgments

I appreciate information on the presence of Atlantic Ghost Crab populations on islands

off the southeast coast of MA, provided by Luanne Johnson, Director, Biodiversity

Works, Edgartown, MA, and Tim Simmons, Restoration Ecologist, Natural Heritage and

Endangered Species Program, West Boylston, MA. David M. Knott, Poseidon Taxonomic

Services, Charleston, SC, has been helpful in directing me to recently documented northern

populations of crabs. I thank Lisa Hutchings, Education Coordinator, Joppa Flats Education

Center, Newburyport, MA, for notifying me and providing photographs and specimens of

ghost crab megalopae found on Plum Island, MA. I appreciate the information provided to

me by William O’Connor on a megalopa from Gloucester, MA. I am grateful to John N.

Kraeuter, Haskin Shellfish Research Laboratory, Rutgers University, Port Norris, NJ, for

providing me with a megalopa collected at Kennebunkport, ME, and also for reviewing an

earlier draft of this paper. Jeremy W. Miller, Wells National Estuarine Research Reserve,

Wells, ME, kindly clarified collection data on the megalopa found in Kennebunk in 2012,

and provided me with photographs taken by Brandon Woo. I thank William S. Johnson,

Goucher College, Baltimore, MD, and Terri Kirby Hathaway, North Carolina Sea Grant,

Manteo, NC, for information related to ghost crabs south of New Jersey. John M. Cushing,

Vienna, VA, shared photographs and information on O. quadrata megalopae collected at

Duck, NC, for which he coined the name “blueberry crabs”. My colleagues Andrew P. de

Wet and Steven Sylvester kindly helped me construct Figure 1, and Franklin and Marshall

College continued to aid and encourage my research. I appreciate the helpful comments and

corrections of the reviewers.

Literature Cited

Crane, J. 1940. Eastern Pacific expedition of the New York Zoological Society. XVIII. On

the post-embryonic development of brachyuran crabs of the genus Ocypode. Zoologica

25:65–82.

Diaz, H., and J.D. Costlow. 1972. Larval development of Ocypode quadrata (Brachyura:

Crustacea) under laboratory conditions. Marine Biology 15:120–131.

Grant, D. 1983. Ghost crabs on Sandy Hook, N.J. Underwater Naturalist 14:25.

Haley, S.R. 1969. Relative growth and sexual maturity of the Texas ghost crab, Ocypode

quadrata (Fabr.) (Brachyura, Ocypodidae). Crustaceana 17:285–297.

Haley, S.R. 1972. Reproductive cycling in the Atlantic Ghost Crab, Ocypode quadrata

(Fabr.) (Brachyura, Ocypodidae). Crustaceana 23:1–11.

Knott, D.M. 2005. Atlantic Ghost Crabs Ocypode quadrata. South Carolina comprehensive

wildlife conservation strategy, DNR, Available online at http:www.dnr.sc.gov/cwcs/pdf/

Ghostcrab.pdf. Accessed 31 October 2012.

Northeastern Naturalist Vol. 20, No. 4

J.J. McDermott

2013

585

Lalli, C.M., and T.R. Parsons. 1991. Biological Oceanography. Pergamon Press, Oxford,

UK. 301 pp.

McDermott, J.J. 1983. Food web in the surf zone of an exposed sandy beach along the mid-

Atlantic coast of the United States. Pp. 529–53, In A. McLachlan and T. Erasmus (Eds.).

Sandy Beaches as Ecosystems. Dr. W. Junk, The Hague, Netherlands.

McDermott, J.J. 1987. The distribution and food habits of Nephtys bucera Ehlers, 1868,

(Polychaeta: Nephtyidae) in the surf zone of a sandy beach. Proceedings of the Biological

Society of Washington 100:21–27.

McDermott, J.J. 1991. A breeding population of the western Pacific crab Hemigrapsus

sanguineus (Crustacea: Decapoda: Grapsidae) established on the Atlantic coast of North

America. Biological Bulletin 181:195–198.

McDermott, J.J. 1998. The western Pacific brachyuran (Hemigrapsus sanguineus; Grapsidae),

in its new habitat the Atlantic coast of the United States: Geographic distribution

and ecology. ICES Journal of Marine Science 55:289–298.

McDermott, J.J. 2001. Biology of Chiridotea caeca (Isopoda: Idoteidae) in the surf zone of

exposed sandy beaches along the coast of southern New Jersey, USA. Ophelia 55:1–13.

McDermott, J.J. 2005. Food habits of the surf-zone isopod Chiridotea caeca (Say, 1818)

(Chaetiliidae) along the coast of New Jersey, USA. Proceedings of the Biological Society

of Washington 118:63–73.

McDermott, J.J. 2009. Notes on the unusual megalopae of the ghost crab Ocypode quadrata

and related species (Decapoda: Brachyura: Ocypodidae). Northeastern Naturalist

16:637–646.

Milne, L.J. and M.J. Milne. 1946. Notes on the behavior of the ghost crab. American Naturalist

80:655–661.

Morris, D.E. 1957. Ghost crabs. Estuarine Bulletin 2:3 (University of Delaware Marine

Laboratories).

Ng, P.K.L., D. Guinot, and P.J.F. Davie. 2008. Systema Brachyurorum: Part I. An annotated

checklist of extant brachyuran crabs of the world. The Raffles Bulletin of Zoology

17:1–286.

Raja Bai Naidu, K.G. 1954. The post-larval development of the shore crab Ocypoda platytarsis

M. Edwards and Ocypoda cordimana Desmarest. Proceedings of the Indian Academy

of Sciences 40:89–101.

Robertson, J.R., and W.J. Pfeiffer 1982. Deposit-feeding by the ghost crab Ocypode quadrata

(Fabricius). Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology 56:165–177.

Roff, J.C., L.P. Fanning, and A.B. Stasko. 1984. Larval crab (Decapoda: Brachyura) zoeas

and megalopas of the Scotian Shelf. Canadian Technical Report of Fisheries and Aquatic

Sciences No. 1264: iv + 22 pp.

Ruppert, E.E., and R.S. Fox. 1988. Seashore Animals of the Southeast: A Guide to Common

Shallow-water Invertebrates of the Southeastern Atlantic Coast. University of South

Carolina Press, Columbia, SC. 429 pp.

Smith S.I. 1873a. Zoology and botany 1. The megalops stage of Ocypode. Journal of Science

3:67–68.

Smith S.I. 1873b. VIII. Report on the invertebrate animals of Vineyard Sound and the adjacent

waters, with an account of the physical characters of the region. C.—The metamposphoses

of the lobster, and other crustacea. Report of the United States Commission

of Fish and Fisheries 1(for 1871–1872):522–537. Washington, DC.

Smith, S.I. 1880. Occasional occurrence of tropical and subtropical species of decapod

Crustacea on the coast of New England. Transactions of the Connecticut Academy of

Arts and Sciences 4:254–267.

586

J.J. McDermott

2013 Northeastern Naturalist Vol. 20, No. 4

Stephensen, E.H., R.S. Steneck, and R.H. Seeley 2009. Possible temperature limits to range

expansion of non-native Asian shore crabs in Maine. Journal of Experimental Marine

Biology and Ecology 375:21–31.

Verrill, A.E. 1873. Report on the invertebrate animals of Vineyard Sound and the adjacent

waters, with an account of the physical features of the region. Pp. 295–778, plates 1–38,

In S.F. Baird (Ed.). Report on the Conditions of the Sea Fisheries of the South Coast of

New England in 1871 and 1872. Vol. 1. United States Commission of Fish and Fisheries,

Washington, DC.

Williams, A.B. 1984. Shrimps, Lobsters, and Crabs of the Atlantic Coast of the Eastern

United States, Maine to Florida. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, DC. 550 pp.

Williams, A.B., and J.J. McDermott. 1990. An eastern United States record of the western

Indo-Pacific crab Hemigrapsus sanguineus (Crustacea: Decapoda: Grapsidae). Proceedings

of the Biological Society of Washington 103:108–109.

Wolcott, T.G. 1978. Ecological role of ghost crabs, Ocypode quadrata (Fabricius) on an

ocean beach: Scavengers or predators? Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and

Ecology 31:67–82.