701

Interspecific Killing of a Branta bernicla (Brant) by a Male

Branta canadensis (Canada Goose)

David A. Krauss1,* and Issa E. Salame2

Abstract - Interspecific killing dissociated from predation is rare in birds. An instance of this

behavior episode in which a male Branta canadensis (Canada Goose) killed a Branta bernicla

(Brant) was observed and photographed on Long Island, NY in April 2011. The Canada Goose

exhibited aggressive nest-defense behavior that is well known for this species, and we suspect that

this aggression combined with the Brant’s inability to defend itself due to its smaller size led to this

unusual result. The male Canada Goose maintained its attack until the Brant die d.

Introduction. Interpretations of interspecific aggression in birds are varied (Murray

1986) and include extroversions of intraspecific aggression (Horn 1988) possibly related

to hormone levels during the breeding season, competition for food (Alexander 1987,

Conover and Kania 1994, Kalinosky 1975) and competition for nest sites (Kalinosky

1975). Such encounters, while significant, rarely produce fatal results although interspecific

aggression at nest sites has been known to cause mortality in some species (Merilä

and Wiggins 1995). Records of such interspecific killing in birds are rare, but those that

exist most often relate to nesting activity. While predation could be considered an aggressive

behavior, it is always intended to result in the death (and consumption) of one of

the individuals involved. In our discussion of aggressive behavior below, only agonistic

behaviors unrelated to predation are considered.

Anseriforms exhibit high levels of nest-site-associated aggression (Black and Owen

1987, Burgess and Stickney 1994, Ciaranka et al. 1997, Ely et al. 1987, Livezey and

Huphrey 1985). Steamer ducks present an extreme example of nest-site aggression.

Being significantly larger and more heavily built than other ducks, aggressive behavior

in steamer ducks often results in interspecific killing (Nuechterlein and Storer 1985).

Although many other species are highly aggressive, we can find no other references to

interspecific killing by Anseriformes. Swans also are highly aggressive at nest sites, a nd

their large size makes them particularly dangerous to smaller waterfowl that they sometimes

kill (Ciaranka et al. 1997). Large body size in the aggressive individual seems to

be an important factor in the occurrence of interspecific killin g among Anseriformes.

Geese are known to be highly aggressive at their nest sites, and much of their social

behavior is related to agonistic interactions on (Akesson and Raveling 1982, Hanson

1953, Gauthier and Tardif 1991, Sedinger and Raveling 1990, ) and off (Gregoire and

Ankney 1990, McLandress and Raveling 1981, Raveling 1970) their breeding grounds.

Branta canadensis (L.) (Canada Goose) males are the primary defenders of their nests,

especially during incubation (Sedinger and Raveling 1990). Although the aggression of

these geese at nest sites is well known (the Oceanside Nature Center where this incident

occurred has warning signs alerting humans to potential goose aggression), this is the

first record of such behavior in the literature. Increases in hormone levels (Akesson and

Raveling 1981, Hirschenhauser et al. 2000) leading up to the breeding season are related

to changes in goose behavior, including increased aggression. Such interspecific aggression

seems to have the evolutionary advantage of protecting the nest site and offspring

from competitors as well as predators.

1Science Department, Borough of Manhattan Community College, 199 Chambers Street, New

York, NY 10007. 2Chemistry Department, City College of New York, 160 Convent Avenue,

New York, NY 10031. *Corresponding Author - dkrauss@bmcc.cuny.ed.

Notes of the Northeastern Naturalist, Issue 19/4, 2012

702 Northeastern Naturalist Vol. 19, No. 4

Observations. We report here an incident in which an aggressive male Canada Goose

attacked and killed a Branta bernicla (L.) (Brant) in defense of its nest 23 April 2011 at

the Oceanside Marine Nature Study Area in Nassau County, Long Island, NY. The majority

of the Canada Geese nesting on Long Island are part of a non-migratory population

(USFWS 2012). The observers were approximately 25–30 m from the birds during the

entire episode. A flock of approximately 35–40 Brant was swimming through a channel

in the salt marsh roughly 30 m from the Canada Goose nest. At approximately 11:30 AM,

an individual Brant, apparently a first-summer bird based on the minor white neck band,

broke from the flock and swam towards the Canada Goose nest. It was unclear why the

Brant moved away from the flock. The birds were not actively feeding, and there did not

appear to be anything that specifically drew the Brant away from the group. Possible

explanations may have been a desire to feed in shallower water or to preen on the shore.

There was no obvious sign of injury or illness in the Brant. The male Canada Goose

rapidly descended from his alert stance near the nest, while the female remained alert on

the nest throughout the entire incident. The male goose immediately attacked the Brant,

vocalizing and charging simultaneously. After a few initial vocalizations, the attack was

silent. The goose pecked and bit the Brant, knocking it down onto its breast as it reached

shallow water (Fig. 1A). In this position, the Brant was essentially helpless and became

mired in the intertidal mud.

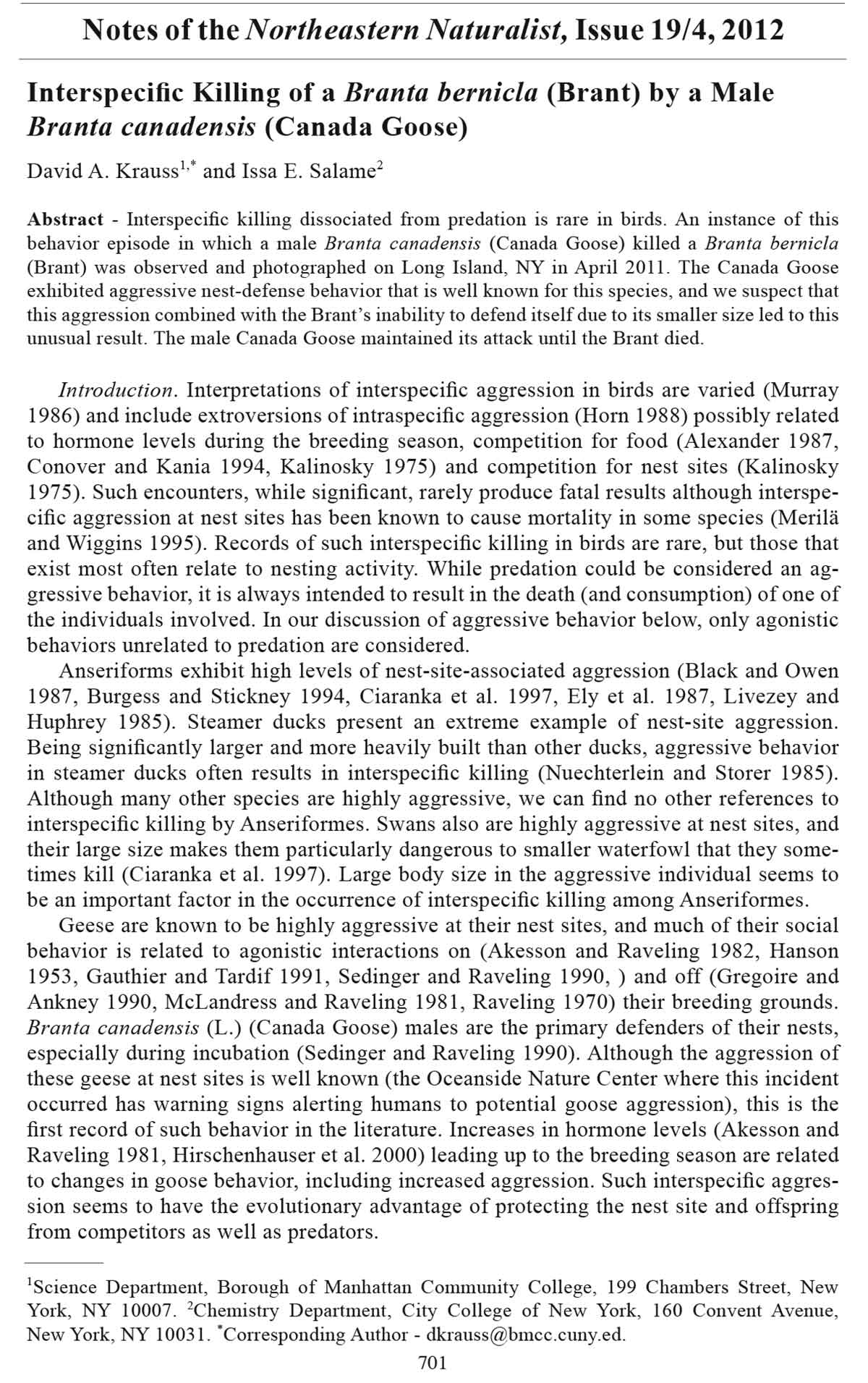

Figure 1. A sequence of photographs taken during a Canada Goose’s attack on a Brant on 23 April

2010 at Oceanside Nature Center, Long Island, NY. A) 11:32 AM: in the early stages of the Canada

Goose’s attack on the Brant, the Brant actively tried to escape as seen here. B) 11:42 AM: the Canada

Goose is forcing the Brant’s head under the water. The goose engaged in this activity repeatedly

limiting the Brant’s access to air, accelerating its exhaustion. C) 11:47 AM: The Brant periodically

lay dormant, appearing unconscious, during the attack. Here the Canada Goose is holding the limp

neck of the unresponsive Brant. D) 12:42 PM: the Canada Goose is forcing the Brant’s head into

the mud. The goose didn’t just push, but hammered the Brant’s head into the mud. Ultimately the

Brant died due to suffocation by mud that clogged its nares.

2012 Northeastern Naturalist Notes 703

By 11:40, the Brant was stuck in the mud and the Canada Goose continued to peck and

bite it, concentrating on the head and neck. The blows caused injury (visible blood) and disorientation

in the Brant. The goose frequently bit the Brant’s head and forced it under water

(Fig. 1B) and/or into the mud. When the Brant lay quiescent in the mud, the goose would

stop pecking. However, as soon as the Brant tried to move away, the goose always resumed

its attack. When the Brant tried to flap its way free, the goose bit its wings.

After approximately 15 minutes from the start of the attack, the Brant seemed exhausted

and frequently lay still in the mud. The Brant appeared to lose consciousness on

numerous occasions (Fig. 1C). If the Brant moved again, the goose resumed its attack.

When the Brant was still, the goose would wait for 20–30 seconds. If the Brant did not

move again within that time span, the goose would peck and bite the Brant hard enough

to rip pieces of skin from the Brant. Whenever the Brant tried to flee, the goose resumed

its attack on the Brant’s head and neck.

Eventually (12:30 PM), the Brant became exhausted and seemed to lack the energy

to pull itself out of the mud. The Canada Goose repeatedly pecked the Brant’s head

into the mud (Fig. 1D). Several times the goose grabbed the Brant’s head and pushed

it, beak first, as far into the mud as it could. The male goose continued to peck at the

Brant carcass for several minutes after it had apparently died of suffocation/drowning.

When the goose could no longer elicit a response from the Brant (12:50 PM), it

returned to its mate on the nest.

The Brant’s role in the entire event was passive and it was apparently unaware of the

goose nest. The only response it made to the goose was to attempt to flee. The Brant never

engaged in any form of agonistic behavior and was never observed attempting to bite

the goose. The remainder of the flock of Brant immediately swam away from the attack

towards deeper water as soon as it began and remained passive at a distance of 30–50 m.

They remained calm and displayed no behavioral signs of agitation after the first few

minutes. Due to the rules of the nature center, it was not possible to retrieve the carcass

of the Brant for study.

Discussion. Interspecific killing dissociated from predation among birds is rarely

reported. Such incidents may occur more commonly than they are reported among aggressive

species like the Canada Goose. Canada Geese aggressively defend their nests

against predators and conspecific rivals as was observed here. Cody (1969) suggested

that similar physical characteristics among closely related species could be associated

with interspecific aggression and this may have been a factor in this incident. There is

no evidence that Canada Geese and Brant hybridize, and it is possible that aggression at

this level may be an important isolating mechanism between these similar species. We

interpret this event as the result of high hormone levels in the male goose resulting in hyper-

aggressive behavior directed towards a Brant that was unable to defend itself against

the larger and more powerful attacker. The Brant may have triggered attack behavior in

the male goose that continued to increase as the Brant was unable to leave the vicinity of

the nest. Early in the nesting season, aggressive behavior may become exaggerated due

to high hormone levels (Akesson and Raveling 1981, Hirschenhaus er et al. 2000).

Literature Cited

Akesson, T.R., and D.G. Raveling. 1981. Endocrine and body weight changes in nesting and nonnesting

Canada Geese. Biology of Reproduction 25:792–804.

Akesson, T.R., and D.G. Raveling. 1982. Behaviors associated with seasonal reproduction and

long-term monogamy in Canada Geese. Condor 84:188–196.

Alexander, W.C. 1987. Aggressive behavior in wintering diving ducks (Aythyini). Wilson Bulletin

99:38–49.

704 Northeastern Naturalist Vol. 19, No. 4

Black, J.M., and M. Owen. 1987. Agonistic behavior in Barnacle Goose flocks: Assessment, investment,

and reproductive success. Animal Behaviour 37:199–209.

Burgess, R.M., and A.A. Stickney. 1994. Interspecific aggression by Tundra Swans toward Snow

Geese on the Sagavanirktok River Delta, Alaska. Auk 111:204–207.

Ciaranca, M.A., C.C. Allin, and G.S. Jones. 1997. Mute Swan (Cygnus olor). No. 273, In A. Poole

and F. Gill (Eds.). The Birds of North America. The Academy of Natural Sciences, Philadelphia,

PA, and The American Ornithologists Union, Washington, DC.

Cody, M.L. 1969. Convergent Characteristics in Sympatric Species: A possible relation to interspecific

competition and aggression. Condor 71:222–239.

Conover, M.R., and G.S. Kania. 1994. Impact of interspecific aggression and herbivory by Mute

Swans on native waterfowl and aquatic vegetation in New England . Auk111:744–748.

Ely, C.R., D.A. Budeau, and U.G. Swain. 1987. Aggressive encounters between Tundra Swans and

Greater White-fronted Geese during brood rearing. Condor 89:420 422.

Gauthier, G., and J. Tardif. 1991. Female feeding and male vigilance during nesting in Greater

Snow Geese. Condor 91:701–711.

Gregoire, P.E., and D. Ankney. 1990. Agonistic behavior and dominance relationships among

Lesser Snow Geese during winter and spring migration. Auk 107:550 560.

Hanson, H. 1953. Interfamily dominance in Canada Geese. Auk 70:11–16.

Hirschenhauser, K., E. Möstl, B. Wallner, J. Dittami, and K. Kotrschal. 2000. Endocrine and behavioral

responses of male Greylag Geese (Anser anser) to pair-bond challenges during the

reproductive season. Ethology 106:63–77.

Horn, A.G. 1988. Interspecific aggression in Western Meadowlarks (Sturnella neglecta): Redirected

aggression? Journal of Field Ornithology 59:224–226.

Kalinosky, R. 1975. Intra- and interspecific aggression in House Finches and House Sparrows.

Condor 77:375–384.

Livezey, B.C., and P.S. Huphrey. 1985. Territoriality and interspecific aggression in steamer ducks.

Condor 87:154–157.

McLandress, M.R., and D.G. Raveling. 1981. Hyperphagia and social behavior of Canada Geese

prior to spring migration. Wilson Bulletin 93:310–324.

Merilä, J., and D.A. Wiggins. 1995. Interspecific aggression for nest holes causes adult mortality

in the Collared Flycatcher. Condor 97:445–450.

Murray, B.G., Jr. 1986. The influence of philosophy on the interpretation of interspecific aggression.

Condor 88: 543.

Nuechterlein, G.L., and R.W. Storer. 1985. Aggressive behavior and interspecific killing by Flying

Steamer Ducks in Argentina. Condor 87:87–91.

Raveling, D.G. 1970. Dominance relationships and agonistic behavior in Canada Geese in winter.

Behaviour 37:291–319.

Sedinger, J.S., and D.G. Raveling. 1990. Parental behavior of cackling Canada Geese during brood

rearing: Division of labor within pairs. Condor 92:174–181.

United States Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS). 2012. Final environmental impact statement:

Resident Canada Goose mmanagement. Available online at http://www.fws.gov/migratorybirds.

Accessed 27 August 2012.