Status and Ecology of a Rare Gomphid Dragonfly at the

Northern Extent of its Range

Jeffrey D. Corser

Northeastern Naturalist, Volume 17, Issue 2 (2010): 341–345

Full-text pdf (Accessible only to subscribers.To subscribe click here.)

Access Journal Content

Open access browsing of table of contents and abstract pages. Full text pdfs available for download for subscribers.

Status and Ecology of a Rare Gomphid Dragonfly at the

Northern Extent of its Range

Jeffrey D. Corser*

Abstract - New records of a rare dragonfly, Stylurus plagiatus, are described from the Hudson

River estuary in eastern New York State. Breeding occurred primarily in tidal mudflats; however,

in other parts of its range, this species is known to use a broader array of habitat types. As

a southerly species at its northern range margin, populations of S. plagiatus in eastern New York

are likely to be temperature-limited, although other factors, such as shoreline habitat integrity

and dispersal behavior, may also play a role in defining its range limits.

The range of the riverine dragonfly Stylurus plagiatus Selys (Russet-tipped

Clubtail) is centered along the Oklahoma/Kansas border, with a northern range

boundary around 43° to 44°N latitude in both the Northeast and upper Midwest

(Craves 2001, Donnelly 2004). This species is generally regarded as being common

in the southern and midwestern United States but rare in the north. At its northern

extent, in New York, Pennsylvania, and New Jersey, it is listed as critically imperiled

(NatureServe 2005), and has never been reported from states or provinces further to

the north and east. Prior to the early 1990s, it was known north of the Long Island/

New Jersey area from a single historical record at Lake George in northeastern New

York (Needham 1928), although the validity of this record is questionable (T. Donnelly,

SUNY Binghamton, Binghamton, NY, pers. comm.). The species was then

rediscovered in September 1991 by Ken Soltesz on the Hudson River estuary (HRE)

in Dutchess County and is currently found northward along the Hudson to the Mohawk

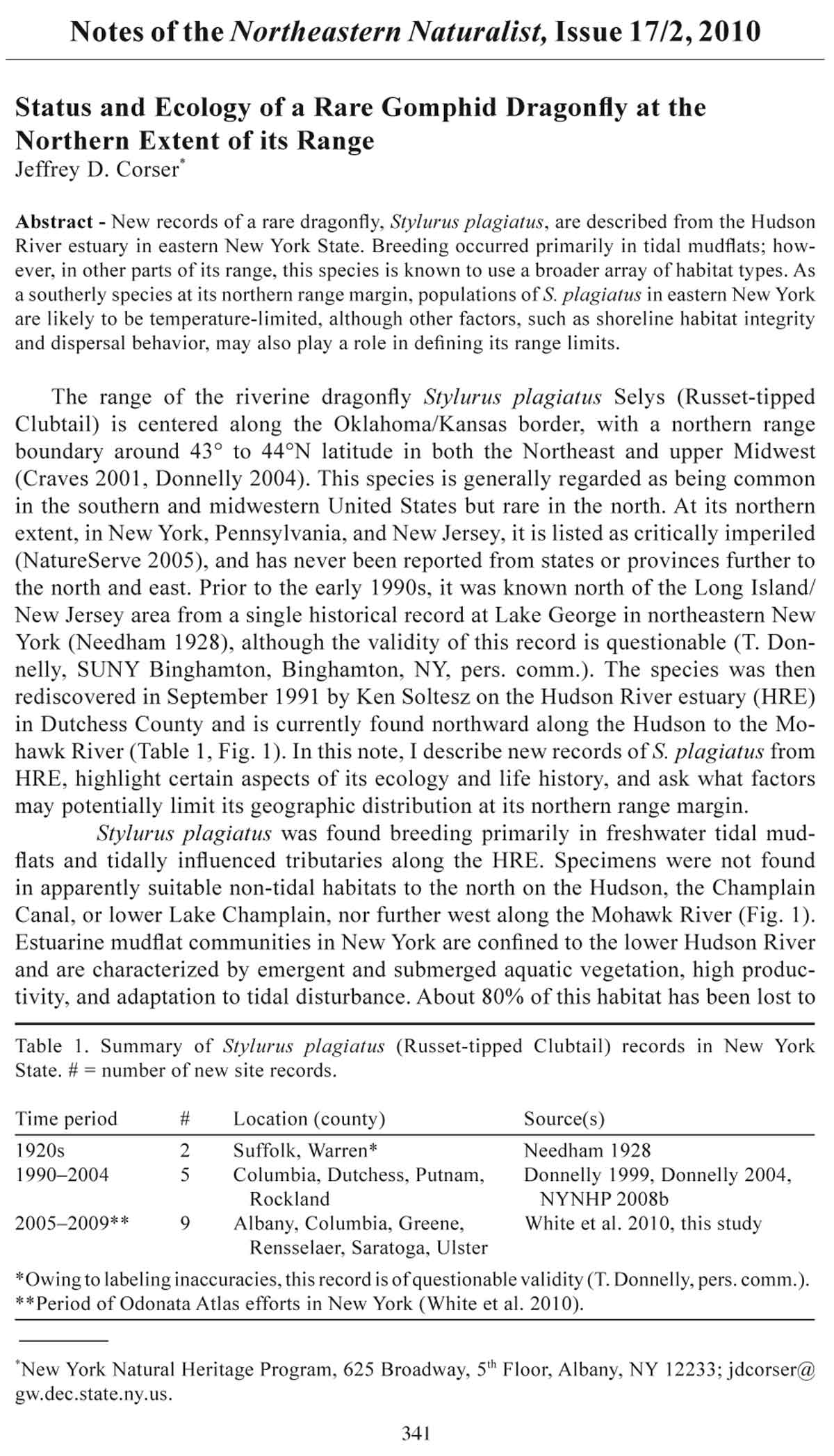

River (Table 1, Fig. 1). In this note, I describe new records of S. plagiatus from

HRE, highlight certain aspects of its ecology and life history, and ask what factors

may potentially limit its geographic distribution at its northern range margin.

Stylurus plagiatus was found breeding primarily in freshwater tidal mudflats and tidally influenced tributaries along the HRE. Specimens were not found

in apparently suitable non-tidal habitats to the north on the Hudson, the Champlain

Canal, or lower Lake Champlain, nor further west along the Mohawk River (Fig. 1).

Estuarine mudflat communities in New York are confined to the lower Hudson River

and are characterized by emergent and submerged aquatic vegetation, high productivity,

and adaptation to tidal disturbance. About 80% of this habitat has been lost to

Notes of the Northeastern Nat u ral ist, Issue 17/2, 2010

341

Table 1. Summary of Stylurus plagiatus (Russet-tipped Clubtail) records in New York

State. # = number of new site records.

Time period # Location (county) Source(s)

1920s 2 Suffolk, Warren* Needham 1928

1990–2004 5 Columbia, Dutchess, Putnam, Donnelly 1999, Donnelly 2004,

Rockland NYNHP 2008b

2005–2009** 9 Albany, Columbia, Greene, White et al. 2010, this study

Rensselaer, Saratoga, Ulster

*Owing to labeling inaccuracies, this record is of questionable validity (T. Donnelly, pers. comm.).

**Period of Odonata Atlas efforts in New York (White et al. 2010).

*New York Natural Heritage Program, 625 Broadway, 5th Floor, Albany, NY 12233; jdcorser@

gw.dec.state.ny.us.

342 Northeastern Naturalist Notes Vol. 17, No. 2

urbanization along the Hudson’s riparian zone (NYNHP 2008a). The species likewise

did not turn up elsewhere in New York during extensive statewide Odonata surveys

during 2005–2009 (White et al. 2010). However, other large rivers in New York may

have been under-surveyed, and the species’ late flight season and cryptic behavior

could have led to under-reporting. In other parts of its range, S. plagiatus appears

less habitat specific, occurring on large rivers, creeks, and even lakes with silty and/

or sandy bottoms (Dunkle 2000).

The larvae of S. plagiatus exhibit microhabitat selection, burrowing deeply

into sand/gravel substrates while feeding on chironomids, tubificid worms, and

Figure 1. The

extent of the

Hudson River

estuary (HRE)

in eastern New

York. The dot

(•) on the Mohawk

River near

its confluence

with the Hudson

represents the

northernmost

occurrence of

Stylurus plagiatus

in the Northeast.

Shed skins

(exuviae), but

not adults, were

found at this

non-tidal locale

in summer 2007

(Hemeon 2007)

and 2008. The

dashed line (---)

represents the

approximate location

of a major

topographic/

climatic boundary

(Pederson et

al. 2004).

2010 Northeastern Naturalist Notes 343

burrowing mayflies, living for one to two years, or possibly longer (Cannings 2003,

Corbet 1999). They emerge at mid-day from late June to early July, the final instar

larvae clinging just above the waterline to emergent vegetation, tree roots, rocks,

and embankments, often in rather residential riverside locations (Hemeon 2007).

The nature of shoreline habitat is critical for S. plagiatus because the newly-emerged

adults fly immediately up to trees and shrubs bordering the riverbank and for the next

couple of months they are seldom observed, presumably (Cannings 2003, Corbet

2006) seeking shelter in mature riparian forests along tidal mudflats. Along the HRE,

breeding commenced the first week of September, and during this time, adults could

often be found in sheltered, forested coves, but activity ceased by late September

as nighttime temperatures cooled. Many other riparian dragonfly species (Samways

and Steytler 1996), including the close relative S. olivaceus (Selys) (Olive Clubtail),

are known to benefit from the maintenance of natural shorelines and the ecological

processes that maintain functioning tidal wetland communities (Cannings 2003).

Butler and deMaynadier (2008) also found that shoreline habitat integrity played an

important role in the diversity of lacustrine damselfly assemblages.

Perching dragonfly species such as S. plagiatus must spend long periods suspended

vertically from tall trees and shrubs as they absorb heat in order to power

their flight (Corbet 1999). The growth and development of egg and larval stages is

also strongly temperature dependent, requiring threshold amounts of heat input (i.e.,

growing degree days) for developmental processes to occur (Pritchard 1982, Pritchard

and Leggott 1987). Therefore, the geographic distribution of these species is

known to be strongly temperature limited (May 1991). Based on an ecological niche

model (e.g., Guisan and Zimmerman 2000, Prasad et al. 2006) that used known S.

plagiatus occurrences in New York and 47 different environmental variables (see

Howard 2006), several different thermal variables such as elevation, growing degree

days, and monthly minimum temperatures (May–July) were found to be key factors

in defining suitable habitats. This finding helps explain why a southerly species like

S. plagiatus would find favorable microclimates along the mild HRE. The northernmost

known occurrence of S. plagiatus (Fig. 1) lies just south of a well-defined

northern range limit of many southerly distributed plant and animal species (e.g.,

Pederson et al. 2004, Stewart and Rossi 1981).

Dragonfly populations are known to shift their ranges in response to regional

temperature changes (Hickling et al. 2005), and Ott (2001) documented the expansion

of more southerly distributed Odonata species into northern Europe as the climate

warmed. Increasing temperatures lead to more rapid development rates (voltinism) of

Gomphid larvae (Braune et al. 2008) and thus earlier emergence of adults, leading to

longer flight seasons (Hassall et al. 2007) and a corresponding extension of northern

range limits. Although the distribution of currently occupied S. plagiatus habitats in

New York appears to be quite restricted, the stability of this northern range margin over

the past 80+ years is in doubt because of the uncertain status of the historical record in

Lake George, Warren County (Table 1). As a result, it is not clear whether the species’

range has contracted or, more likely, has been expanding northward as the climate has

warmed in the Hudson Valley (Pederson et al. 2004). If S. plagiatus in New York is

characteristic of other range-margin insect species (Thomas et al. 2001), its potential to

further expand its range beyond HRE will depend on both larvae and adults responding

to novel environments far from the center of their distribution, and incorporating ecological

(habitat) as well as evolutionary (dispersal) adaptations.

344 Northeastern Naturalist Notes Vol. 17, No. 2

Acknowledgments. Erin White helped with the Figure and offered suggestions

which improved earlier drafts of the manuscript, as did Paul Novak, Nick

Donnelly, Matt Schlesinger, Tim Howard, Jason Bried, and two anonymous reviewers.

Kevin Hemeon generously contributed his collection of exuviae and

provided helpful feedback. Paul Novak verified adult specimens. Survey work

was supported by the Biodiversity Research Institute and the NYS Department of

Environmental Conservation.

Literature Cited

Braune, E., O. Richter, D. Söndgerath, and F. Suhling. 2008. Voltinism flexibility of a riverine

dragonfly along thermal gradients. Global Change Biology 14:470–482.

Butler, R.G., and P.G. deMaynadier. 2008. The significance of littoral and shoreline habitat

integrity to the conservation of lacustrine damselflies (Odonata). Journal of Insect Conservation

12:23–36.

Cannings, S.G. 2003. Status of Olive Clubtail (Stylurus olivaceus) in British Columbia. BC

Ministry of Water, Land, and Air Protection, Biodiversity Branch, Victoria, BC, Canada.

Wildlife Bulletin No. B-112.

Corbet, P.S. 1999. Dragonflies: Behavior and Ecology of Odonata. Cornell University Press,

Ithaca, NY. 829 pp.

Corbet, P.S. 2006. Forests as habitats for dragonflies (Odonata). Pp. 13–36, In A.C. Rivera

(Ed.). Forests and Dragonflies. Fourth WDA Symposium of Odonatology, Pensoft Publishers,

Sofia, Bulgaria. 299 pp.

Craves, J.A. 2001. Notable new dragonfly records. Williamsonia 5:5–6.

Donnelly, T.W. 1999. The Dragonflies and Damselflies of New York. Prepared for the 1999

International Congress of Odonatology and 1st Symposium of the Worldwide Dragonfly

Association. July 11–16, 1999. Colgate University, Hamilton, NY. 39 pp.

Donnelly, T.W. 2004. Distribution of North American Odonata. Part I: Aeshnidae, Petaluridae,

Gomphidae, Cordulegasteridae. Bulletin of American Odonatology 7:61–90.

Dunkle, S.W. 2000. Dragonflies Through Binoculars: A Field Guide to Dragonflies of North

America. Oxford University Press, New York, NY. 266 pp.

Guisan, A., and N.E. Zimmerman. 2000. Predictive habitat distribution models in ecology.

Ecological Modelling 135:147–186.

Hassall, C., D.J. Thompson, G.C. French, and I.F. Harvey. 2007. Historical changes in the phenology

of British Odonata are related to climate. Global Change Biology 13:933–941.

Hemeon, K. 2007. Gimme some skin (Exuviae). Vermont Entomological Society News

57:10–11.

Hickling, R, D.B. Roy, J.K. Hill, and C.D. Thomas. 2005. A northward shift of range margins

in British Odonata. Global Change Biology 11:502–506.

Howard, T.G. 2006. Salmon River watershed inventory and landscape analysis. New York

Natural Heritage Program. Albany, NY. 177 pp. Available at http://www.tughill.org.

May, M.L. 1991. Thermal adaptations of dragonflies, revisited. Advances in Odonatology

5:71–88.

NatureServe. 2005. NatureServe Explorer: An online encyclopedia of life. Available online at

http://www.natureserve.org/explorer. Accessed 20 October 2008

Needham, J.G. 1928. Odonata. Pp. 45–56, In M.D. Leonard (Ed.). A List of the Insects of New

York. Cornell University Press, Ithaca, NY.

NYNHP. 2008a. Online conservation guide for freshwater intertidal mudflats. Available online

at http://guides.nynhp.org/guide.php?id=9870. Accessed 5 November 2008.

NYNHP. 2008b. Online conservation guide for Stylurus plagiatus. Available online at http://

guides.nynhp.org/guide.php?id=8361. Accessed 5 November, 2008. NYNHP. 2009. New

York dragonfly and damselfly survey database. New York Natural Heritage Program, Albany,

NY.

2010 Northeastern Naturalist Notes 345

Ott, J. 2001. Expansion of Mediterranean Odonata in Germany and Europe—Consequences

of climatic changes. Pp. 89–111, In G.R. Walther, C.A. Burga, and P.J. Edwards (Eds.).

“Fingerprints” of Climate Change: Adapted Behavior and Shifting Species Ranges. Plenum

Publishers, New York, NY.

Pederson, N., E.R. Cook, G.C. Jacoby, D.M. Peteet, and K.L. Griffin. 2004. The influence of

winter temperatures on the annual growth of six northern range-margin tree species. Dendrochronologia

22:7–29.

Prasad, A.M., L.R. Iverson, and A. Liaw. 2006. Newer classification and regression tree techniques:

Bagging and random forests for ecological prediction. Ecosystems 9:181–199.

Pritchard, G. 1982. Life-history strategies in dragonflies and the colonization of North America

by the genus Argia (Odonata: Coenagrionidae). Advances in Odonatology 1:227–241.

Pritchard, G., and M.A. Leggott. 1987. Temperature, incubation rates, and origins of dragonflies. Advances in Odonatology 3:121–126.

Samways, M.J., and N.S. Steytler. 1996. Dragonfly (Odonata) distribution patterns in urban and

forest landscapes, and recommendations for riparian management. Biological Conservation

78:279–288.

Stewart, M.M., and J. Rossi. 1981. The Albany Pine Bush: A northern outpost for southern species

of amphibians and reptiles in New York. American Midland Naturalist 106:282–292.

Thomas, C.D., J. Bosworth, R.J. Wilson, A.D. Simmons, Z.G. Davies, M. Musche, and L.

Conradt. 2001. Ecological and evolutionary processes at expanding range margins. Nature

411:577–581.

White, E.L., J.D. Corser, and M.D. Schlesinger. 1010. The New York Dragonfly and Damselfly

Survey 2005–2009: Distribution and Status of the Odonata of New York. Department of

Environmental Conservation, New York Natural Heritage Program, Albany NY.