Florida Grasshopper Sparrow Distribution, Abundance, and Habitat Availability

Michael F. Delany, Matthew B. Shumar, Molly E. McDermott, Paul S. Kubilis, James L. Hatchitt, and Rosanna G. Rivero

Southeastern Naturalist, Volume 6, Number 1 (2007): 15–26

Full-text pdf (Accessible only to subscribers.To subscribe click here.)

2007 SOUTHEASTERN NATURALIST 6(1):15–26

Florida Grasshopper Sparrow Distribution, Abundance,

and Habitat Availability

Michael F. Delany1,*, Matthew B. Shumar2, Molly E. McDermott3,

Paul S. Kubilis1, James L. Hatchitt4, and Rosanna G. Rivero1

Abstract - Remote sensing, geographical information system applications, and

ground and aerial assessments revealed a fragmented distribution of 44,933 ha of

potential habitat for the endangered Ammodramus savannarum floridanus (Florida

Grasshopper Sparrow) with most of this habitat (30,262 ha, 67%) located on conservation

lands. A continued decrease in available habitat since 1996 was indicated.

Searches of potential habitat and information from surveys at known locations found

278 male Florida Grasshopper Sparrows at seven sub-populations during 2004. No

previously unknown breeding aggregations were found. The current distribution

evinces a considerable contraction in range compared to historic distribution; however,

other breeding aggregations may exist on private property (10,718 ha) where

access was denied. Three formerly large sub-populations on Avon Park Air Force

Range have declined and are now near extirpation. The low number of individuals

and the paucity and fragmented distribution of suitable dry prairie will be limiting

factors for recovery of this sedentary subspecies. Habitat expansion and management,

and demographic improvements at existing locations may restore some Florida

Grasshopper Sparrow sub-populations. Large areas (> 377 ha) of protected potential

habitat in Manatee, DeSoto, and Glades counties offer the best opportunities for the

establishment of additional sub-populations (> 50 pairs) to achieve recovery goals.

The cooperative effort of public land managers from various agencies and of private

landowners will be needed to prevent the extinction of this bird.

Introduction

Ammodramus savannarum floridanus Mearns (Florida Grasshopper

Sparrow) is an endangered subspecies endemic to the south-central prairie

region of Florida (USFWS 1999). Breeding aggregations (sub-populations)

are known from only 6 locations, and fewer than 1000 individuals may exist

(Delany et al. 1999). The recovery objective is to down-list the sparrow to

threatened when > 10 protected locations contain stable, self-sustaining subpopulations

of > 50 breeding pairs (USFWS 1999). However, only two

extant sub-populations—Three Lakes Wildlife Management Area (WMA)

and Kissimmee Prairie Preserve State Park—meet recovery criteria. One

other protected sub-population occurs on the Prairie Lakes Unit of Three

Lakes WMA, and 3 sub-populations occur on Avon Park Air Force Range.

Florida Grasshopper Sparrows on protected lands are monitored with annual

1Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission, 4005 South Main Street,

Gainesville, FL 32601. 2PO Box 32, Donegal, PA 15628. 343 Francis Street,

Uniontown, PA 15401. 4Armasi Inc., 3966 Southwest 98th Drive, Gainesville, FL

32608. *Corresponding author - mike.delany@myFWC.com.

16 Southeastern Naturalist Vol. 6, No. 1

point-count surveys, and grassland habitat is maintained for sparrows with

prescribed fire every 2 to 3 years (Delany et al. 1999). Basic information on

population trends and habitat use is needed to develop and implement

conservation strategies for the sparrow (USFWS 1999).

Florida’s dry prairie is a variable and poorly known suite of plant communities

(Bridges and Reese 1999). The habitat type is characterized as flat,

open expanses dominated by fire-dependent grasses, Serenoa repens (Bart.)

Small (saw palmetto), and low shrubs (Abrahamson and Hartnett 1990). Dry

prairie occupied by Florida Grasshopper Sparrows (Fig. 1) is treeless and

ranges from thick (34% shrub cover), low (57 cm) saw palmetto scrub to

grass pastures with a sparse (< 10% shrub cover) or patchy cover of shrubs

and saw palmetto (Delany et al. 1985). The area of native prairie in Florida

has been greatly reduced by agriculture (Davis 1967), and this probably

caused the extirpation of the sparrow from some former breeding locations

(Delany and Linda 1994). The conversion of natural habitats on private

lands in south-central Florida to agriculture and urban development is accelerating

(Kautz 1998, Kautz et al. 1993), and continued habitat fragmentation

will have detrimental effects on the Florida Grasshopper Sparrow (Perkins et

al. 2003).

Potential habitat needs to be identified and searched for additional Florida

Grasshopper Sparrows (Delany et al. 1999, USFWS 1999). Our objectives

were to ascertain the current location of potential habitat for Florida Grasshopper

Sparrows in south-central Florida and determine the distribution and

abundance of the subspecies. We used remote sensing and GIS applications to

Figure 1. Dry prairie on Avon Park Air Force Range, Highlands County, FL. The

location was dominated by saw palmetto and native grasses, and occupied by Florida

Grasshopper Sparrows. Photograph © by Barry Mansell.

2007 M.F. Delany et al. 17

identify and map potential habitat. Areas of potential habitat were verified and

searched for Florida Grasshopper Sparrows, and information was obtained on

the status of sub-populations on protected lands.

Methods

Potential habitat for Florida Grasshopper Sparrows was estimated from a

consensus of several data sources and confirmed by ground and aerial

assessments. We obtained digital land-cover information for south-central

Florida (30-m resolution, 1994 and 1995 Landsat Thematic Mapper data)

processed into standard land-cover types, and a data file of Universal Transverse

Mercator (UTM) coordinates for 1672 individual Florida Grasshopper

Sparrow locations derived from point-count surveys and banding data from

across all habitat occupied during 1996–1999 (Delany et al. 1999). Using

ArcView (ESRI 1990) software, the Landsat land-cover file was overlain on

the file of sparrow locations to determine the dominant land cover of occupied

areas. Water Management District land-use land-cover (LULC) files

from 1995 identifying pasture, shrub and brush land, and mixed rangeland

categories also were projected to create a complementary profile to verify

land-cover results from the Landsat analysis. Areas similar in composition

to occupied locations (potential habitat) were identified in Florida south of

28o 30' latitude, and polygons surrounding each area were digitized using

ArcView (ESRI 1990). Because A. savannarum Gmelin (Grasshopper Sparrows)

avoid small grassland patches and forested edges (Vickery 1996),

polygons < 100 ha or with a narrow configuration (< 1128 m wide, the

diameter of a 100-ha circle) were excluded from the dataset.

Because the Landsat dry prairie land-cover category included opencanopy

pineland (10–15% cover) unsuitable for Grasshopper Sparrows,

scanned aerial photographs (3-m resolution, USGS 1995 digital orthographic

quarter quads) were geo-referenced to the polygon vector data to

detect trees. Polygon outlines were viewed with aerial photograph backdrops

and visually inspected. Polygons containing trees were eliminated

from the dataset or redrawn to exclude tree cover. Distances between the

edges of polygons were measured using ArcView (ESRI 1990). Landowners

of potential habitat were determined using Land Use Mapping System

(LUMS) property appraiser data files and county plat maps.

The dry prairie land-cover category and Ilex glabra [L.] Gray

(gallberry)/saw palmetto compositional group (a shrub and graminoid

community associated with wet flatwoods) were portrayed when Florida

Grasshopper Sparrow locations were viewed in context with the Landsat

land-cover data. However, some occupied areas showed very little of either

land cover. The LULC data generally coincided with the satellite data, but

also indicated some potential habitat where there was no indication of the

dry prairie or gallberry/saw palmetto land coverage based on the Landsat

data. In this case, the LULC data were presumed to be something other

than potential habitat and were not included. In cases where the amount of

18 Southeastern Naturalist Vol. 6, No. 1

relevant Landsat coverage was sparse (< 25%) but overlain by relevant

LULC data, it was included in the delineation of potential habitat.

Landowners and managers were mailed information about the Florida

Grasshopper Sparrow and contacted by telephone for permission to verify

habitat suitability and conduct sparrow surveys. We visited areas of potential

habitat to assess their suitability and determine if a search for Florida

Grasshopper Sparrows was appropriate. Habitat evaluations were based on:

1) vegetative cover—the presence of species characteristic of the dry prairie

plant community and the absence of trees; 2) vegetation structure indicative

of recent fire—grasslands that were low in height (< 100 cm) with about

20% bare-ground; and 3) landscape context—large (> 100 ha) areas with a

configuration that minimizes edge, and proximity to other patches of suitable

habitat. Our criteria for designating potential habitat were similar to

those used by Shriver and Vickery (1999) to describe “high quality habitat”

for Florida Grasshopper Sparrows.

From 7 April to 22 May 2004, surveys were conducted between 0650 and

0955 by two to four searchers who walked transects at 200-m intervals across

potential habitat, stopping frequently to make visual and auditory observations.

Transect start and end points were recorded with a GPS unit (Magellan

GPS 300 and 315). Surveys were conducted during low-wind (< 10 km/hr)

conditions and during mornings with no fog or precipitation. A tape recording

of the territorial song of the male Grasshopper Sparrow was used to elicit

responses from any males in the area. Information was obtained on the

presence or absence of Florida Grasshopper Sparrows, survey location, and

general habitat description. Information on the status of populations on public

lands during 2004 was obtained from land managers who conducted pointcount

surveys according to Walsh et al. (1995). Point-count survey methods

were the same for all years and locations (three 5-minute unlimited-distance

observations during the breeding season); however, the number of points

sampled differed by year at some locations.

Because of concerns of land-use restrictions if an endangered species

was found, most private landowners denied access to verify habitat (40

polygons), and owners of four polygons could not be contacted. For these

areas, visual assessments were conducted aerially from a Bell Jet Ranger

helicopter during 16.1 hours of flight time at an altitude of < 122 m from 7

February to 28 March 2006. Flights were first made over areas of Three

Lakes WMA and Kissimmee Prairie Preserve State Park currently occupied

by Florida Grasshopper Sparrows, to develop an aerial search image

for suitable habitat. A GPS receiver and topographical maps were used to

navigate to the center point of each polygon of potential habitat where

access was denied. Large polygons were circled until a complete view of

the area was obtained. “High quality” habitat identified during 1996 aerial

assessments by Shriver and Vickery (1999) also were visited to determine

their current suitability, and we searched for additional potential habitat

during flights.

2007 M.F. Delany et al. 19

Results

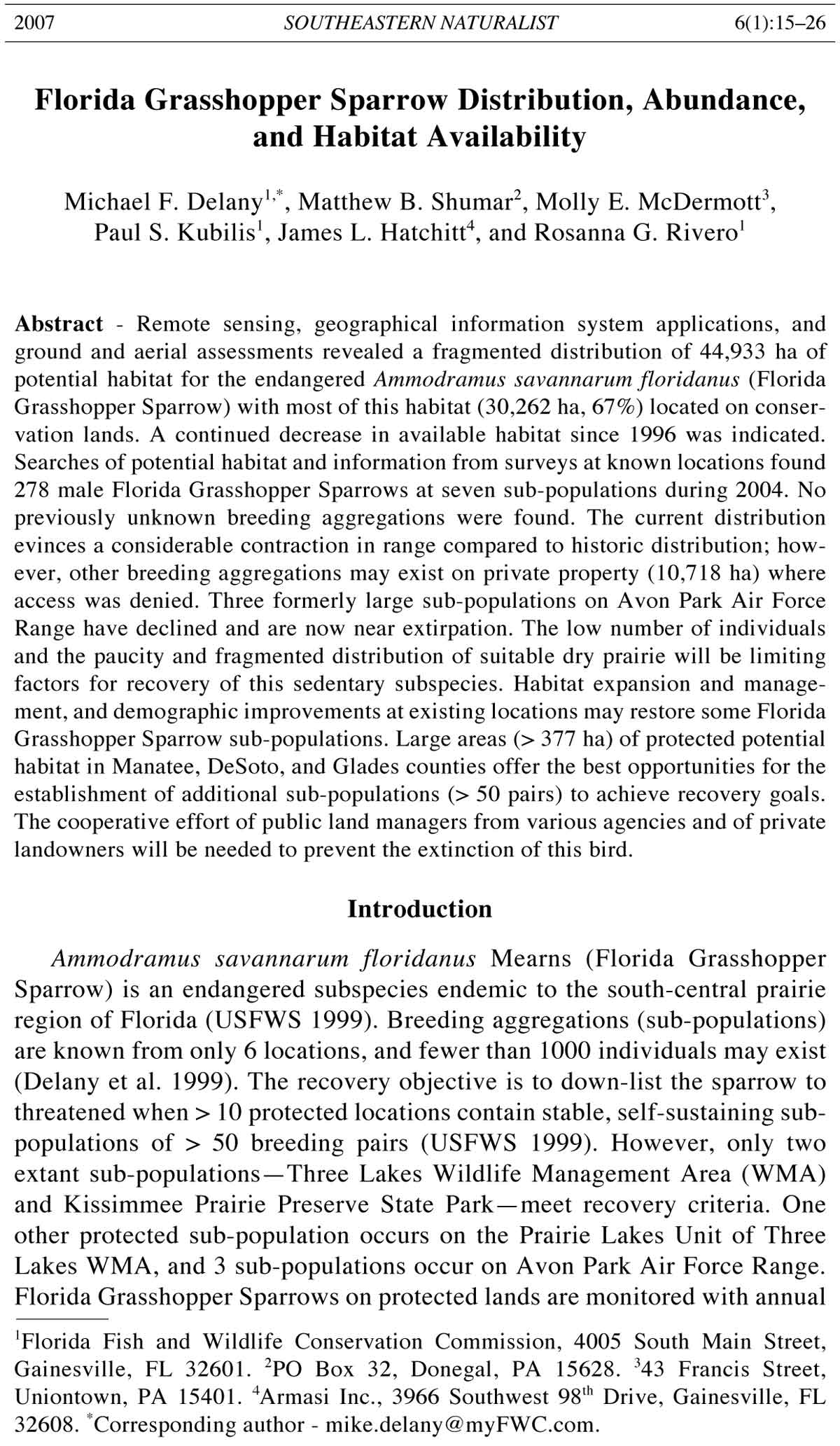

Remote-sensing and GIS applications, and ground and aerial verification

revealed a fragmented distribution of potential habitat (44,933 ha)

for Florida Grasshopper Sparrows (Fig. 2), with most of this habitat

(30,262 ha, 67%) on protected lands. Mean polygon size was 1248 ha (SD

= 1248, N = 36) and ranged from 233 to 5355 ha. Mean distance from the

edge of extant sub-populations to the edge of the nearest unoccupied

polygon was 10.4 km (SD = 9.01, N = 7) and ranged from 2.3 to 29.3 km.

Large-scale maps and landowner or manager contact information are

available from the senior author.

We searched for Florida Grasshopper Sparrows in 12 polygons, obtained

data for seven polygons on conservation areas that were sampled

during existing point-count surveys, and acquired information on a subpopulation

on private property (USFWS 2002) (Figs. 2 and 3). A total of

278 male Florida Grasshopper Sparrows were detected at seven disjunct

Figure 2. Areas

(36 polygons) of

potential habitat

for Florida Grasshopper

Sparrows

derived from

1994 and 1995

Landsat Thematic

Mapper data,

land-use/landcover

files, aerial

photographs, and

2004 ground and

2006 aerial assessments.

Black

polygons were

occupied by Florida

Grasshopper

Sparrows, darkgray

polygons

were searched but

no Florida Grasshopper

Sparrows

were detected,

and light gray

polygons were

unsearched because

access was

denied.

20 Southeastern Naturalist Vol. 6, No. 1

sub-populations: Three Lakes WMA (2), Avon Park Air Force Range (3),

Kissimmee Prairie Preserve State Park (1), and the privately owned Beaty

Ranch (1; USFWS 2002). Sparrow occurrence on Kissimmee Prairie Preserve

State Park was considered to be one sub-population, and distribution

reflects the location of point-count survey sampling grids. Survey results

from 2004 are in Table 1, and specific locations of extant sub-populations

are shown in Figure 3. No previously unknown breeding aggregations were

Figure 3. Conservation areas (light gray), polygons of potential habitat (dark gray),

and locations of Florida Grasshopper Sparrows (black), 2004. For Avon Park Air

Force Range, locations are from top to bottom: Bravo Range, OQ Range, and Echo

Range. Florida Grasshopper Sparrows on Kissimmee Prairie Preserve State Park

were considered one sub-population.

2007 M.F. Delany et al. 21

found. For all potential habitat detected, Florida Grasshopper Sparrow subpopulations

occupied 10 polygons (20,852 ha), 11 polygons (13,364 ha)

were surveyed without detecting additional birds, and 15 polygons (10,718

ha) were unsearched.

Discussion

Most potential habitat for Florida Grasshopper Sparrows occurred in

disjunct patches within the former dry prairie land cover mapped by Davis

(1967). Our delineation of potential habitat using remote sensing and GIS

applications detected four of the seven locations known to be occupied.

Bravo Range was not selected because the amount of relevant Landsat

coverage was sparse (< 25%) and not supported by LULC data. Though the

site was occupied, a high percentage of bare-ground cover at this military

target classified it as disturbed land marginally suitable for Grasshopper

Sparrows. The Prairie Lakes Unit of Three Lakes WMA was not selected

because of changes in vegetation since Landsat data were obtained. Rollerchopping

and prescribed fire since 1999 improved habitat for the sparrow,

and translocation of 18 juveniles to this location during 2001 and 2002

(Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission [FWC], Tallahassee,

FL, unpubl. data) may have established a new sub-population. The location

of an estimated 12–20 male Florida Grasshopper Sparrows in a 371-ha

Paspalum sp. L. (bahia grass) pasture and 3 males in an adjacent 17-ha

pasture on the Beaty Ranch in Okeechobee County (USFWS 2002) were not

detected in our search for potential habitat or during aerial surveys by

Table 1. Number of male Florida Grasshopper Sparrows detected during distribution and point

count surveys at all known locations, 1996–1998 and 2004. The number of point count stations

is in parentheses.

Males Males Prairie

Location County 1996–1998A 2004 (ha) Source

Three Lakes WMA S. Glass, FWCB

Main population Osceola 94 (161) 124 (169) 4000

Prairie Lakes Unit Osceola – 6 841

Avon Park Air Force Range J. Tucker, ABSC

Bravo Range Polk 21 (39) 1 (39) 581

OQ Range Highlands 49 (67) 4 (82) 700

Echo Range Highlands 67 (119) 10 (118) 1195

Kissimmee Prairie PreserveD Okeechobee 111 (137) 107 (188) 8470 P. Miller, DEPE

Adams RanchF Osceola – 18 171 This study

Beaty Ranch Okeechobee – 8 388 USFWS, unpubl.

data

AFrom Delany et al. (1999). Point count survey methods were the same as in 2004. Each point

sampled about 12 ha.

BFlorida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission.

CArchbold Biological Station.

DNot all available habitat was sampled. This population is probably much larger.

EDepartment of Environmental Protection.

FContiguous with main population at Three Lakes WMA.

22 Southeastern Naturalist Vol. 6, No. 1

Shriver and Vickery (1999). Improved pastures (plowed and planted with

non-native grasses) were not considered potential habitat for Florida Grasshopper

Sparrows (see Delany and Linda 1994). A breeding location in an

improved pasture on Kissimmee Prairie Preserve State Park was similarly

overlooked. Advantages and caveats associated with remote sensing and

GIS applications in ornithological research were reviewed by Shaw and

Atkinson (1990) and Glen and Ripple (2004). Despite some errors, Landsat

coverage supported by other relevant data sources were useful not only to

perform initial assessment of occupied and potential habitats, but also to

optimize the process of selection and delineation of these areas. However,

after this initial stage, ground and aerial assessments were the best methods

to verify habiat suitability and improved our results.

Searches of large areas of potential habitat on Myakka River State Park

(718 ha, Manatee County) and conservation easements in DeSoto County

(782 ha) (this study) and Glades County (2490 ha) (Delany et al. 2000) failed

to locate Florida Grasshopper Sparrows. Areas of seemingly potential habitat

are often unoccupied by the sparrow (Howell 1932, Walsh et al. 1995).

Some patches of dry prairie may be unused because of their isolation from

extant sub-populations.

Historically, most dry prairie was found within the Kissimmee River

Basin and west of Lake Okeechobee (Davis 1967). Because of variation in

methods and the inclusion of different plant communities, estimates of the

extent of historical dry prairie and changes in coverage are difficult to

interpret. Kautz et al. (1993) calculated 830,000 ha of pre-settlement dry

prairie from Davis (1967), and used 1985–1989 Landsat imagery to estimate

561,114 ha of remaining dry prairie statewide in the 1980s. Shriver and

Vickery (1999) estimated that only 19% (156,000 ha) of the original dry

prairie remained in central peninsular Florida, and their aerial assessment of

eight counties identified 63,968 ha of “high-quality” habitat for Florida

Grasshopper Sparrows in 1996. Our estimate of 44,933 ha of suitable dry

prairie indicates a continued loss of potential habitat for Florida Grasshopper

Sparrows. Compared to results from Shriver and Vickery (1999), we

identified smaller patches of dry prairie and found potential habitat outside

their search area.

Previous information indicated a more widespread distribution of Florida

Grasshopper Sparrows (reviewed in Stevenson and Anderson 1994) and may

reflect a formerly greater coverage of dry prairie. The current distribution of

Florida Grasshopper Sparrows at only seven locations within about 900 km2

evinces a considerable contraction in range compared to their historic occurrence.

The six males found on the Prairie Lakes Unit of Three Lakes WMA

(3.2 km from the main population) may be a recently formed breeding

aggregation due to habitat improvements and translocation of sparrows. Not

all potential habitat was sampled at Kissimmee Prairie Preserve State Park,

so this sub-population is probably larger than our data indicate. All three

sub-populations on Avon Park Air Force Range have declined in size and are

2007 M.F. Delany et al. 23

near extirpation. Intermittent extirpations of small populations (< 10 individuals)

of grassland birds are to be expected (Curnutt et al. 1996); however,

the synchronous decrease of formerly large sub-populations (see Delany et

al. 1999, and Shriver and Vickery 1999) at Avon Park Air Force Range is

cause for concern.

The low number of Florida Grasshopper Sparrows and the paucity and

fragmented distribution of suitable dry prairie will be limiting factors for

recovery. Current protected areas of dry prairie may not provide adequate

habitat to meet recovery goals. In addition to Three Lakes WMA and

Kissimmee Prairie Preserve State Park, eight additional sub-populations of

> 50 breeding pairs are needed to down-list the sparrow to threatened

(USFWS 1999). A sub-population of > 50 breeding pairs of Florida Grasshopper

Sparrows may require 1348 ha of contiguous prairie habitat

(Delany et al. 1995). We found 12 polygons that met this size criterion,

with 11 located entirely or partly on protected lands, including 6 polygons

with extant sub-populations. One 1392-ha polygon of potential habitat was

located entirely on private property in southwest Highlands County.

Perkins et al. (2003) recommended 4000 ha of prairie to support a subpopulation,

but only three polygons of potential habitat met their size

criterion. Habitat expansion and management and demographic improvements

may restore Florida Grasshopper Sparrows on Avon Park Air Force

Range. With further land-management and translocation efforts, the Prairie

Lakes Unit of Three Lakes WMA also may support a sub-population of >

50 pairs. Because of its large size and protection, potential habitat on

Myakka River State Park (Manatee County) and conservation easements in

DeSoto and Glades counties offer the best opportunities for the establishment

of additional sub-populations to achieve recovery goals. However,

these locations were > 47.4 km from extant Florida Grasshopper Sparrows.

Banding studies indicated that dispersal limitations imposed by habitat

fragmentation may be problematic for the formation of new sub-populations

(Delany et al. 1995, Perkins and Vickery 2001, but see Miller 2006). The

distance between extant sub-populations and the nearest potential habitat

(> 2.3 km) may inhibit colonization. Although even low dispersal rates can

promote the persistence of meta-populations (Brown and Kodric-Brown

1977), recovery of this sparrow may require active translocation to facilitate

the formation of new sub-populations. The efficacy of experimental translocations

at Three Lakes WMA need to be evaluated. Methods and results of

translocations need to be thoroughly documented (Fischer and Lindenmayer

2000, Scott and Carpenter 1987), and pending evaluation, other locations

assessed for possible translocations. Without adequate habitat acquisition

and management to improve connectivity, translocation may be an important

alternative for saving endangered species (Lublow 1996).

Increasing the area of dry prairie and improving the connectivity of subpopulations

were the most effective management options for improving the

viability of the Florida Grasshopper Sparrow (Vickery and Perkins 2003).

24 Southeastern Naturalist Vol. 6, No. 1

Larger prairies (> 4000 ha) would support a greater number of sparrows, and

a concomitant increase in core area (> 400 m from edge) may improve

reproduction (Perkins et al. 2003). Because Grasshopper Sparrow density

and reproduction is usually negatively correlated with edge (Vickery 1996),

the shape of grasslands (perimeter to area ratio) should also be a factor in

land acquisition, restoration, and management.

Immediate and intensive efforts are needed to restore Florida Grasshopper

Sparrows on Avon Park Air Force Range. The sparrow appears to be responsive

to habitat improvements (Delany 1996, Perkins and Vickery 2005), and

management actions (e.g., adequate prescribed fire to reduce woody vegetation

and promote grass coverage, and removal of intervening and encroaching

woody vegetation) may promote optimal breeding conditions (see Delany and

Linda 1998a,b) and expand potential habitat. The feasibility of restoring

improved pastures to more prairie-like conditions should be investigated to

increase potential habitat in former dry prairie once occupied by Florida

Grasshopper Sparrows. Although plant species composition may differ from

native prairie, structural features of restored grasslands may provide suitable

breeding habitat for Grasshopper Sparrows (Fletcher and Koford 2002). The

removal of pine plantations to improve the connectivity of sub-populations

should be considered.

Other breeding aggregations may exist on unsearched private lands

where access was denied, and landowners should be contacted periodically

for permission to conduct surveys. Search efforts should be expanded to

include improved pastures with some remaining native vegetation that may

provide suitable breeding habitat, and Florida Grasshopper Sparrow reproductive

success in these improved pastures needs to be determined. The

cooperative effort of public land managers from various agencies as well as

private landowners will be needed to prevent the loss of this sparrow.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the Florida Nongame Wildlife Trust Fund and US Air

Force through US Army medical research acquisition activity award DAMD 17-00-2-

0023, and USFWS grant agreement 401815G180. We thank P. Ebersbach, P.B. Walsh,

S.M. Cumberbatch, T.F. Dean, K.B. Donnelly, and L.M. Torres, who effectively

promoted this effort. This publication does not necessarily reflect the position or policy

of the US Government, and no official endorsement should be inferred. We thank L.

Adams (Adams Ranch, Inc.), R. Bateman (Bright Hour Ranch), M. Chanen (Cargill

Fertilizer), G. Paul (Bob Paul, Inc.), R. Overstreet (Overstreet Ranch), C. Wilson (Latt

Maxcy Corp.), and M. Folk and S. Woiak (The Nature Conservancy’s Disney Wilderness

Preserve) for access to private property. M.H. Friedman and J.W. Tucker, Jr.

participated in surveys. T. Macklin piloted the helicopter and helped search for dry

prairie. J. Bridges, D. Donaghy, P. Miller, D. Myers, D. Smith, and W. VanGelder

provided logistical support. S. Glass, J. W. Tucker, Jr., and P. Miller provided

information about Florida Grasshopper Sparrow populations on public lands. K.E.

Miller, T.E. O’Meara, D.W. Perkins, J.F. Quinn, Jr., J.A. Rodgers, Jr., and two

anonymous reviewers commented on previous drafts of this paper.

2007 M.F. Delany et al. 25

Literature Cited

Abrahamson, W.G., and D.C. Hartnett. 1990. Pine flatwoods and dry prairies, Pp.

103–129, In R.L. Myers and J.J. Ewel (Eds.). Ecosystems of Florida. University

of Central Florida Press, Orlando, FL. 765 pp.

Bridges, E., and G. Reese. 1999. Micro-habitat characteristics of Florida Grasshopper

Sparrow habitat. Report to the US Department of Defense, Avon Park Air

Force Range, Avon Park, FL. 202 pp.

Brown, J., and A. Kordric-Brown. 1977. Turnover rates in insular biogeography:

Effect of immigration on extinction. Ecology 58:445–449.

Curnutt, J.L., S.L. Pimm, and B.A. Maurer. 1996. Population variability of sparrows

in space and time. Oikos 76:131–144.

Davis, J.H. 1967. General map of natural vegetation of Florida. Institute of Food and

Agricultural Sciences, Agricultural Experiment Stations, Circular S-178, University

of Florida, Gainesville, FL.

Delany, M.F. 1996. Florida Grasshopper Sparrow. Pp. 128–136, In J.A. Rodgers, Jr.,

H.W. Kale II, and H.T. Smith (Eds.). Rare and endangered biota of Florida. Vol.

5, Birds. University Press of Florida, Gainesville, FL. 688 pp.

Delany, M.F., and S.B. Linda. 1994. Characteristics of occupied and abandoned

Florida Grasshopper Sparrow territories. Florida Field Naturalist 22:106–109.

Delany, M.F., and S.B. Linda. 1998a. Characteristics of Florida Grasshopper Sparrow

nests. Wilson Bulletin 110:136–139.

Delany, M.F., and S.B. Linda. 1998b. Nesting habitat of Florida Grasshopper Sparrows

at Avon Park Air Force Range. Florida Field Naturalist 26:33–39.

Delany, M.F., H.M. Stevenson, and R. McCracken. 1985. Distribution, abundance,

and habitat of the Florida Grasshopper Sparrow. Journal of Wildlife Management

49:626–631.

Delany, M.F., C.T. Moore, and D.R. Progulske, Jr. 1995. Territory size and movements

of Florida Grasshopper Sparrows. Journal of Field Ornithology 66:305–309.

Delany, M.F., P.B. Walsh, B. Pranty, and D.W. Perkins. 1999. A previously unknown

population of Florida Grasshopper Sparrows on Avon Park Air Force

Range. Florida Field Naturalist 27:52–56.

Delany, M.F., D.S. Biggs, and P. Petkov. 2000. Florida Grasshopper Sparrow survey,

Phase I Perpetual Conservation Easement, Glades County Florida. Fish and

Wildlife Conservation Commission, Tallahassee, FL. 3 pp.

Environmental Systems Research Institute, Inc., Redlands, CA. (ESRI) 1990.

ArcView 3.0 GIS software.

Fletcher, R.J., and R.R. Koford. 2002. Habitat and landscape associations of breeding

birds in native and restored grasslands. Journal of Wildlife Management

66:1011–1022.

Fischer, J., and D.B. Lindenmayer. 2000. An assessment of the published results of

animal relocations. Biological Conservation 96:1–11.

Glenn, E.M., and W.J. Ripple. 2004. On using digital maps to assess wildlife habitat.

Wildlife Society Bulletin 32:852–860.

Howell, A.H. 1932. Florida Bird Life. Coward-McCann, New York, NY. 579 pp.

Kautz, R.S. 1998. Land-use and land-cover trends in Florida 1936–1995. Florida

Scientist 61:171–187.

Kautz, R.S., D.T. Gilbert, and G.M. Mauldin. 1993. Vegetative cover in Florida

based on 1985–1989 Landsat Thematic Mapper Imagery. Florida Scientist

56:135–154.

26 Southeastern Naturalist Vol. 6, No. 1

Lublow, B.C. 1996. Optimal translocation strategies for enhancing stochastic

metapopulation viability. Ecological Applications 6:1268–1280.

Miller, P. 2006. Long-distance dispersal of a Florida Grasshopper Sparrow. Florida

Field Naturalist 33:123–124.

Perkins, D.W., and P.D. Vickery. 2001. Annual survival of an endangered passerine,

the Florida Grasshopper Sparrow. Wilson Bulletin 113:211–216.

Perkins, D.W., and P.D. Vickery. 2005. Effects of altered hydrology on the breeding

ecology of the Florida Grasshopper Sparrow and Bachman’s Sparrow. Florida

Field Naturalist 33:29–40.

Perkins, D.W., P.D. Vickery, and W.G. Shriver. 2003. Spatial dynamics of sourcesink

habitats: Effects on rare grassland birds. Journal of Wildlife Management

67:588–599.

Scott, J.M., and J.W. Carpenter. 1987. Release of captive-reared or translocated

endangered birds: What do we need to know? Auk 104:544–545.

Shaw, D.M., and S.F. Atkinson. 1990. An introduction to the use of geographic

information systems for ornithological research. The Condor 92:564–570.

Shriver, W.G., and P.D. Vickery. 1999. Aerial assessment of potential Florida

Grasshopper Sparrow habitat: Conservation in a fragmented landscape. Florida

Field Naturalist 27:1–36.

Stevenson, H.M., and B.H. Anderson. 1994. Grasshopper Sparrow. Pp. 638–641, In

The Birdlife of Florida. University Press of Florida, Gainesville, FL. 892 pp.

US Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) 1999. Recovery for the Florida Grasshopper

Sparrow. Pp. 4-387–4-391, In South Florida multi-species recovery

plan. US Fish and Wildlife Service, Vero Beach, FL. 2172 pp.

US Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) 2002. Biological opinion 4-1-02-F-145.

US Fish and Wildlife Service, Vero Beach, FL.

Vickery, P.D. 1996. Grasshopper Sparrow (Ammodramus savannarum). In The

Birds of North America, No. 239 (A. Poole and F. Gill, Eds.). Academy of the

Natural Sciences, Philadelphia, and American Ornithologist’s Union, Washington,

DC.

Vickery, P.D., and D.W. Perkins. 2003. Population viability analysis for Florida

Grasshopper Sparrow. Report to USFWS, Vero Beach, FL. 51 pp.

Walsh P.B., D.A. Darrow, and J.G. Dyess. 1995. Habitat selection by Florida

Grasshopper Sparrows in response to fire. Proceedings of the Annual Conference

of the Southeastern Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies 49:340–347.

The Southeastern Naturalist is a peer-reviewed journal that covers all aspects of natural history within the southeastern United States. We welcome research articles, summary review papers, and observational notes.

The Southeastern Naturalist is a peer-reviewed journal that covers all aspects of natural history within the southeastern United States. We welcome research articles, summary review papers, and observational notes.