2018 Southeastern Naturalist Notes Vol. 17, No. 4

N90

A.J. Phillips, B.W. Williams, and A.L. Braswell

Observations of Cocoon Deposition, Emergence, and Feeding in

Philobdella floridana (Verrill)

Anna J. Phillips1, Bronwyn W. Williams2,*, and Alvin L. Braswell2

Abstract - Philobdella floridana, a species of leech in the family Macrobdellidae, occupies a broad,

yet seemingly patchy, distribution in the Piedmont and Atlantic Coastal Plain regions of the southeastern

US. A recent collection of an adult P. floridana from North Carolina gave us a unique opportunity

to observe several poorly understood, and previously mischaracterized, aspects of the ecology of the

species, including cocoon deposition, emergence of young from cocoons, and feeding behavior. In

addition, we provide new records of P. floridana, extending its known distribution northward in both

the Piedmont and Coastal Plain. Our observations provide important insight into the reproduction,

diet, and habitat of a widespread yet little understood leech species.

The genus Philobdella is part of the family Macrobdellidae, which also includes the

North American medicinal leeches (Phillips and Siddall 2005, 2009). Philobdella is not

species rich, represented only by Philobdella floridana (Verrill) and Philobdella gracilis

Moore. Philobdella floridana is known to occupy a seemingly patchy distribution extending

from southern Florida north to southeastern North Carolina, disjunct from its congener

P. gracilis, which occurs from southern Mississippi and Louisiana northwards in the Mississippi

River Basin to southern Illinois (Moser et al. 2011, Phillips and Siddall 2005, Sawyer

and Shelley 1976). As is typical of leeches with no known commercial or medicinal value,

basic ecological information is poorly understood for both Philobdella species.

The little that is known of the ecology of Philobdella derives in large part from Viosca

(1962), who documented his observations of the habitat, behavior, and presumed host affiliation

of Philobdella gracile (= P. gracilis) in Louisiana. Viosca reported the species to be

most frequently found in mud or under logs at the edge or in shallows of swamps, marshes,

bayous, or in canals or ditches. He listed several species of herpetofauna as hosts (i.e., prey,

or “victims” sensu Viosca 1962), noting that frog eggs seemed particularly vulnerable to

predation by P. gracilis. Viosca suggested that this leech was not known to feed on fishes,

humans, or invertebrates, with the rare exceptions of snails an d crayfishes.

Our only insight into reproduction in Philobdella species came from a report and illustration

of a cocoon discovered under a rock above the water line at the edge of a stream in

South Carolina (Sawyer and Shelley 1976). The authors attributed the cocoon to P. gracilis

(= P. floridana sensu Phillips and Siddall 2005). Habitat and prey preferences of P. floridana

are almost entirely unknown, but are assumed to mirror those reported by Viosca (1962) for

P. gracilis.

A recent collection of an adult P. floridana from Wake County, NC, provided us with a

unique opportunity to document previously unknown—or mischaracterized—aspects of the

ecology of the species. Here, we detail cocoon deposition, hatching, and feeding of P. floridana,

and update our understanding of the distribution of the species.

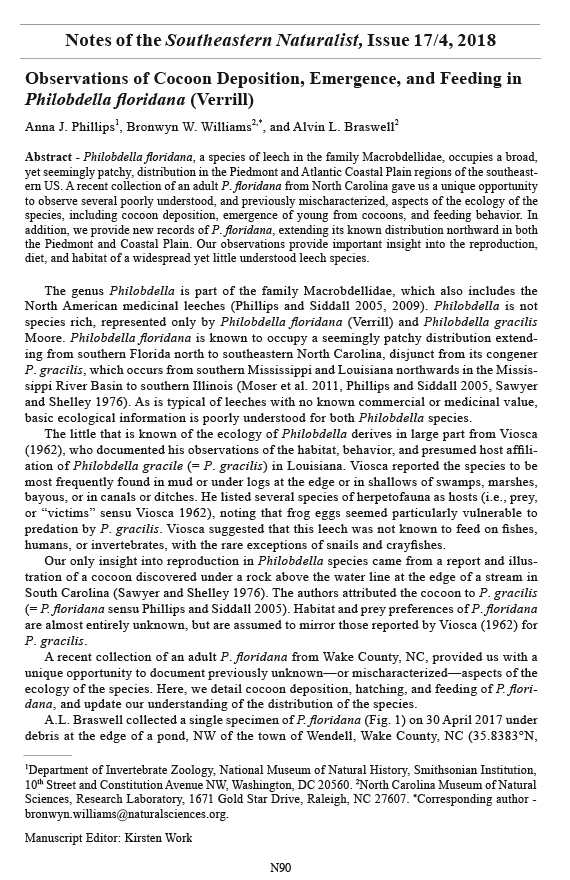

A.L. Braswell collected a single specimen of P. floridana (Fig. 1) on 30 April 2017 under

debris at the edge of a pond, NW of the town of Wendell, Wake County, NC (35.8383°N,

1Department of Invertebrate Zoology, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution,

10th Street and Constitution Avenue NW, Washington, DC 20560. 2North Carolina Museum of Natural

Sciences, Research Laboratory, 1671 Gold Star Drive, Raleigh, NC 27607. *Corresponding author -

bronwyn.williams@naturalsciences.org.

Manuscript Editor: Kirsten Work

Notes of the Southeastern Naturalist, Issue 17/4, 2018

N91

2018 Southeastern Naturalist Notes Vol. 17, No. 4

A.J. Phillips, B.W. Williams, and A.L. Braswell

78.41671°W). Habitat at the head of the pond was mixed pine/hardwoods. The leech was

sampled just below a spring seepage area. We kept the individual alive in a plastic container

with leaves, and fed it an earthworm at 3–5-d intervals. We placed a paper towel dampened

with spring water in the container to maintain humidity and changed the towel every few

days. Approximately 3 weeks following capture, on ~20–21 May 2017, a cocoon measuring

14.2 mm in length, 9.8 mm in width and 7.4 mm in height appeared on the leaf pack

(Fig. 1). The cocoon resembled a stiffened ball of foam, superficially similar to that reported

for other jawed leech species, e.g., Macrobdella decora (Say), Hirudo medicinalis L., and

Haemopis sanguisuga (L.) (Maitland et al. 2000, Moore 1923). We separated the cocoon

from the adult leech, placing it and its leaf in a new container; we maintained the humidity

as above. On 12 June 2017, we observed a second cocoon, measuring 11.8 mm in length, 8.2

mm in width and 6.2 mm in height, alongside the adult leech, and subsequently transferred

it to a separate container.

We observed 6 juvenile P. floridana in the container with the first cocoon on 19 June

2017, 3–4 weeks post-deposition. We were unable to observe the container from 13 to19

June; thus, we could not gauge precise length of time between cocoon deposition and hatching.

The 6 juveniles were ~1.5 cm in length at rest. We observed a 7th juvenile the following

day that was noticeably smaller, ~1 cm in length at rest. On 21 June we counted a total of

10 juvenile P. floridana in the container.

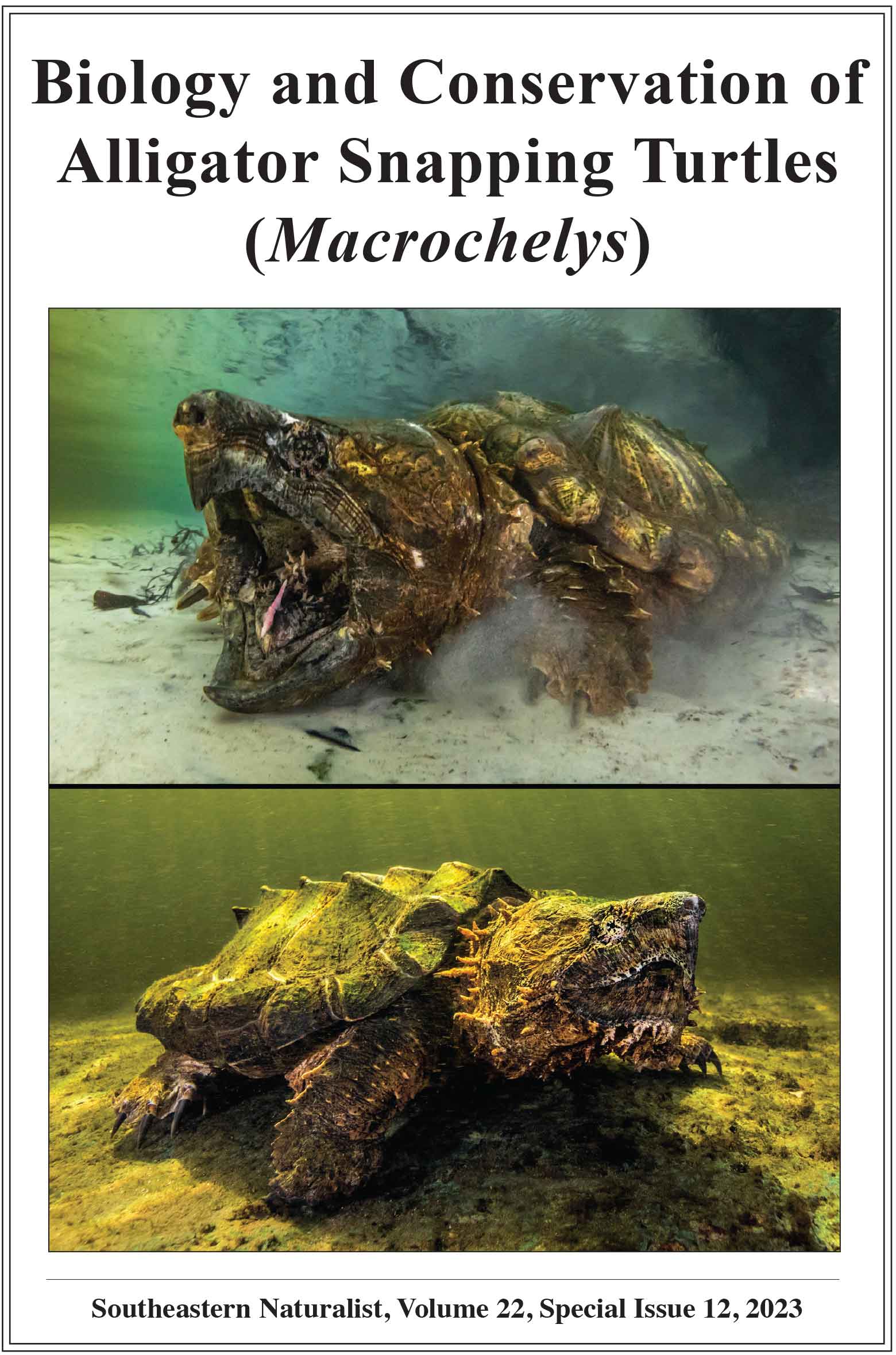

On 21 June we introduced a small earthworm, 2–3 mm in diameter, to the container

containing the 10 juveniles. One nearby leech responded almost immediately, moving

towards the earthworm with rapidity. It attached near the anterior end of the earthworm

and remained affixed while the earthworm continued to move around the container. Within

minutes, 2 additional juvenile P. floridana had attached to the earthworm (Fig. 2A). After

~20 minutes, the earthworm was noticeably paler in color, and its movements had largely

ceased. Several additional leeches latched onto the prey. Approximately an hour after introducing

the earthworm to the container, it had been almost entirely consumed (Fig. 2B).

Figure 1. Adult Philobdella floridana (NCSM 29800) collected near Wendell, Wake County, NC. Inset

shows the first cocoon deposited by this leech in situ.

2018 Southeastern Naturalist Notes Vol. 17, No. 4

N92

A.J. Phillips, B.W. Williams, and A.L. Braswell

We first observed hatchlings in the container with the second cocoon on 27 June 2017,

~2 weeks following deposition. Two additional juveniles appeared on 5 July. By 7 July, a

total of 5 juvenile P. floridana had emerged from this cocoon.

We fixed the 2 cocoons in 80% ethanol ~1 week after emergence of the last juvenile.

We also fixed 2 series of juveniles from the first hatch in 80% ethanol: 4 individuals were

fixed on 22 June (3 d after hatching), and 3 individuals on 15 July (26 d after hatching).

The adult P. floridana was fixed in 80% ethanol on 15 July. We deposited all specimens in

the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences Non-Molluscan Invertebrate Collection

(NCSM 29800–29804). Little is known about the reproductive biology of many leech species,

particularly taxa that are not cultured for medicinal or commercial purposes. The only

information in the literature regarding reproduction in P. floridana was a report in Sawyer

and Shelley (1976) of a cocoon bearing 9 embryos. It is not clear why Sawyer and Shelley

(1976) attributed their cocoon to Philobdella, as the illustration (Sawyer and Shelley

1976:80) is wholly inconsistent with those deposited by our captive adult P. floridana, and

ironically, given our observations above, resembles the cocoon of an aquatic earthworm.

Unfortunately, we have been unable to locate the cocoon reported by Sawyer and Shelley

(1976) for examination; although the authors provided a catalog number for this specimen

(USNM 51696), we found 2 adult P. floridana, but no cocoon in the associated lot.

Cocoons deposited by our captive adult P. floridana were similar in structure and form

to those described for several other jawed leech species, including Hirudo medicinalis,

Haemopis sanguisuga, Limnatis nilotica (Savigny), and most notably the confamilial Macrobdella

decora (Maitland et al. 2000, Moore 1923, Negm-Eldin et al. 2013). Deposition of

2 cocoons in short succession after isolation indicated that sperm can be stored and released

in batches for more than 1 fertilization event, although we do not know if this strategy is

typical in natural populations, or dependent on environmental cues. Interestingly, half the

number of juveniles emerged from the second cocoon as had from the first, and in approximately

half the time. As we did not notice any appreciable differences in size of juveniles

from the 2 emergence events, we suspect that expedited development offset any benefits that

may have been gained from crowding relief inside the cocoon. Emergence from the cocoon

did not occur en masse, but rather was staggered over the span of several days.

Our collection of P. floridana in Wake County represents only the 4th record of this species

from North Carolina, and is the northernmost record of its distribution in the Piedmont

Figure 2. (A) Three juvenile leeches attached to the external surface of an earthworm. (B) A cluster of

6 juvenile leeches engorging on what remained of the earthworm after an hour of feeding.

N93

2018 Southeastern Naturalist Notes Vol. 17, No. 4

A.J. Phillips, B.W. Williams, and A.L. Braswell

physiographic region. The distribution of P. floridana in the Piedmont is poorly understood;

nearly all historical records of the species are in the Atlantic Coastal Plain, ranging from

just south of the type locality, Lake Okeechobee, FL, north to Lake Phelps, NC (Moser et

al. 2011, unpub. record in NCSM Non-Molluscan Invertebrate Collection). A recent collection

of P. floridana from Pohick Bay, VA (USNM 1480598), reported for the first time here,

extends the known range of the species in the Coastal Plain and in toto.

The geographic distribution of P. floridana in its entirety is based on little more than

2 dozen specimens housed in scientific collections and a few unverified published records

(Klemm 1982, Moser et al. 2011, Sawyer and Shelley 1976). The paucity of unique locality

records of the species likely reflects sampling bias rather than rarity. Recent collections of

P. floridana, including those we document here, have been from beneath debris or logs at

the edge of a waterbody, consistent with Viosca’s (1962) observations of P. gracilis. These

habitats are not typically searched during standard aquatic surveys (e.g., for macroinvertebrates

or fishes); leeches encountered during such survey efforts are rarely identified to an

informative taxonomic level. Further, P. floridana, similar to its congener P. gracilis, is not

known to feed on humans (A.J. Phillips, pers. observ.; Viosca 1962). Consequently, human

activity in the water, such as swimming or wading, does not incite predatory behavior in

P. floridana as it would for confamilial blood feeders such as Macrobdella spp. As such, we

expect that P. floridana is encountered incidentally and infrequently, or via targeted surveys

of particular, and undersampled, habitats.

In captivity, our adult P. floridana readily fed on live earthworms, an observation that,

although seemingly inconsistent with Viosca (1962), is not without precedence. Verrill (1874)

noted that the type specimen upon which the original description of Macrobdella floridana

(= P. floridana) was based was preserved in the act of consuming a “small lumbricoid worm”.

Indeed, earthworms may comprise a substantial component of the diet of P. floridana, given

the habitat in which the leeches have been found. Earthworms are typically abundant in damp

soils beneath logs or leaf packs in riparian areas. These habitats are also frequently occupied

by a variety of herpetofauna, which in turn may provide P. floridana with alternative feeding

opportunities. Viosca (1962) listed several species of herpetofauna as hosts for P. gracilis,

and it is reasonable to think that similar prey items might be exploited by P. floridana. Although

our observations during this study do not explicitly speak to feeding preferences of

P. floridana, diet is likely influenced by prey availability.

Viosca’s account of prey use of P. gracilis is particularly interesting as it closely

resembles those reported for Macrobdella ditetra Moore. Macrobdella species are wellknown

for blood feeding from a variety of vertebrate hosts, and have been observed to feed

on floating egg masses laid by frogs during spring breeding (Beckerdite and Corkum 1973;

Moore 1901, 1953; Smith 1977). Macrobdella ditetra is unusual within the genus because

it is not known to feed on humans, a behavior Viosca (1962) reported for P. gracilis. Macrobdella

and Philobdella are sister groups within the family Macrobdellidae (Phillips and

Siddall 2005, 2009), and it may be that reported similarity in diet results from a combination

of phylogenetic similarity and shared habitat, and therefore resources. The distribution of

Macrobdella ditetra overlaps that of both Philobdella species (Klemm, 1982).

Our observations of feeding behavior of newly emerged juvenile P. floridana are novel,

and provide insight into the ecology of this poorly understood life stage. Unlike the adult,

which fed by locating and grasping the anterior end of an earthworm, steadily drawing it

whole into the mouth, the juveniles were limited by gape size. As such, they attached to

the body wall of the earthworm, pierced it, and fed on their prey by sucking internal fluid

and tissues through the breached cuticle. This method of feeding is similar to that used by

branchiobdellidans, small leech-like annelids that are obligate ectosymbionts primarily

2018 Southeastern Naturalist Notes Vol. 17, No. 4

N94

A.J. Phillips, B.W. Williams, and A.L. Braswell

of crayfishes, when presented with prey too large to ingest whole (Gelder and Williams

2015a, b). Multiple juveniles attached to the earthworm soon after it was introduced to the

container (Fig. 2A), and as a group, were clearly able to slow the movements of their prey;

however, it is likely that this interesting pack behavior was not coordinated or cooperative,

but resulted from individual predatory cues. This interpretation is supported by our observations

of additional captive leeches when multiple adults have attacked and fed on the same

prey item.

Acknowledgments. We thank Jan Weems (NCSM) for her support and patience in allowing numerous

captive leeches to reside in her kitchen for part of this study, and William Moser (USNM) for

providing us with the Pohick Bay record of P. floridana. We are also grateful to Patricia G. Weaver

(NCSM) for helpful guidance with manuscript preparation.

Literature Cited

Beckerdite, F.W., and K.C. Corkum. 1973. Observations on the life history of the leech Macrobdella

ditetra (Hirudinea: Hirudinidae). Proceedings of the Louisiana Academy of Sciences 36:61–63.

Gelder, S.R., and B.W. Williams. 2015a. Class Clitellata: Branchiobdellida. Pp. 551–563, In J.H.

Thorp and D.C. Rogers (Eds.). Thorp and Covich’s Freshwater Invertebrates, 4th Edition, Vol. I:

Ecology and General Biology. Academic Press, Amsterdam, Netherlands. 1148 pp.

Gelder, S.R., and B.W. Williams. 2015b. Global overview of Branchiobdellida (Annelida: Clitellata).

Pp. 628–653, In T. Kawai, Z. Faulkes, and G. Scholtz (Eds.). Freshwater Crayfish: Global Overview.

CRC Press, London, UK. 679 pp.

Klemm, D.J. 1982. The Leeches (Annelida: Hirudinea) of North America. EPA/600/3-82/025 (NTIS

PB82208679), US Environmental Protection Agency, Washington, DC.

Maitland, P.S., D.S. Phillips, and M.J. Gaywood. 2000. Notes on distinguishing the cocoons and the

juveniles of Hirudo medicinalis and Haemopis sanguisuga (Hirudinea). Journal of Natural History

34 (5):685–692.

Moore, J.P. 1901. The Hirudinea of Illinois. Bulletin of the Illinois State Laboratory of Natural History

5:479–547.

Moore, J.P. 1923. The control of blood-sucking leeches, with an account of the leeches of Palisades

Interstate Park. Roosevelt Wild Life Bulletin Syracuse (also Syracuse University Bulletin vol.

23), 2:9–53.

Moore, J.P. 1953. Three undescribed American leeches. Notulae Naturae of the Academy of Natural

Sciences of Philadelphia 250:1–13.

Moser, W.E., D.J. Klemm, A.J. Phillips, S.E. Trauth, R.G. Neal, J.W. Stanley, M.B. Connior, and J.E.

Flotemersch. 2011. Distribution of the genus Philobdella (Macrobdellidae: Hirudinida) including

new locality records from Arkansas and Oklahoma. Comparative Parasitology 78 (2):387–391.

Negm-Eldin, M.M., M.A. Abdraba, and H.E. Benamer. 2013. First record, population ecology, and

biology of the leech Limnatis nilotica in the Green Mountain, Libya. Travaux de l’Institut Scientifique,

Rabat, Série Zoologie 49:37–42.

Phillips, A.J., and M.E. Siddall. 2005. Phylogeny of the New World medicinal leech family Macrobdellidae

(Oligochaeta: Hirudinida: Arhynchobdellida). Zoologica Scripta 34 (6):559–564.

Phillips, A.J., and M.E. Siddall. 2009. Poly-paraphyly of Hirudinidae: Many lineages of medicinal

leeches. BMC Evolutionary Biology 9:246.

Sawyer, R.T., and R.M. Shelley. 1976. New records of leeches (Annelida: Hirudinea) from North and

South Carolina. Journal of Natural History 10:65–97.

Smith, D.G. 1977. The rediscovery of Macrobdella sestertia Whitman (Hirudinea: Hirudinidae).

Journal of Parasitology 63(4):759–760.

Viosca, P. 1962. Observations on the biology of the leech Philobdella gracile Moore in southeastern

Louisiana. Tulane Studies in Zoology and Botany 9:243–244.

Verrill, A.E. 1874. Synopsis of the North American freshwater leeches. Report of the United States

Commissioner of Fisheries 1872–73, Pt II: 666–689.

The Southeastern Naturalist is a peer-reviewed journal that covers all aspects of natural history within the southeastern United States. We welcome research articles, summary review papers, and observational notes.

The Southeastern Naturalist is a peer-reviewed journal that covers all aspects of natural history within the southeastern United States. We welcome research articles, summary review papers, and observational notes.