N51

2018 Southeastern Naturalist Notes Vol. 17, No. 3

J.R. Marty, S.A. Collins, and J.M. Whitaker

Extralimital Records of Louisiana-Banded Mottled Ducks

Recovered in North Dakota

Joseph R. Marty1,*, Samantha A. Collins1, and James M. Whitaker1

Abstract - Anas fulvigula (Mottled Duck) is a non-migratory year-round resident species of the

western Gulf Coast and peninsular Florida. We report on 2 male Mottled Ducks banded in southwest

Louisiana and harvested in south central North Dakoa, having traveled a minimum of 1991 km. It is

unknown whether these birds paired with migratory female A. platyrhynchos (Mallard) during fall–

winter 2016 and subsequently followed them to a breeding area in North Dakota, or whether these

birds themselves may have been hybrid offspring of such a pairing. Previous extralimital records of

Mottled Ducks have been reported in the Prairie Pothole region, but our data represent the northernmost

records for this species. Increasing extralimital reports of Mottled Ducks or hybrid ducks should

be cause for concern among conservation planners. Additional research into Western Gulf Coast

Mottled Duck genetics and hybridization rates is warranted.

Anas fulvigula Ridgway (Mottled Duck) is a non-migratory waterfowl species endemic

to the western Gulf Coast and peninsular Florida (Fig 1; Baldassarre 2014, Stutzenbaker

1988, Wilson 2007). Genetic analyses and band-recovery data indicate 2 genetically and

geographically distinct subspecies, A. fulvigula fulvigula Ridgway (Florida Mottled Duck)

and the A. f. maculosa Sennett (Western Gulf Coast Mottled Duck) (McCracken et al.

2001). Additionally, a small but expanding population of Mottled Ducks resides in South

Carolina as a result of a coordinated release of Texas, Louisiana, and Florida birds during

1975–1983 (Kneece 2016). The western Gulf Coast and South Carolina populations inhabit

coastal marshes, inland coastal prairies, and inland agricultural lands (e.g., production

and fallow rice fields), whereas the Florida population inhabits freshwater wetlands and

marshes, ponds, and ditches throughout the Florida peninsula (Baldassarre 2014, Bielefeld

et al. 2010). Few records of western Gulf Coast Mottled Ducks have occurred outside of

the coastal marsh and prairie regions of Louisiana and Texas, which often extend 80–160

km inland from the coastline (Selman et al. 2011, Stutzenbaker 1988). Previous confirmed

band-return records have occurred as far inland as Iowa, Indiana, and South Dakota for the

western Gulf Coast population and as far north as New Jersey from the Florida population

(Baldassarre 2014, Dinsmore and Brees 2007).

Recent studies and mid-winter aerial survey data indicate the Gulf Coast Mottled Duck

population is experiencing declines (Moon 2014; Louisiana Department of Wildlife and

Fisheries, Baton Rouge, LA, unpubl. data). The Mottled Duck is classified as a species of

greatest conservation need in Louisiana (S4; Holcomb et al. 2015) and Texas Wildlife Action

Plans (Texas Parks and Wildlife Department 2012), and has been identified as a priority

species for the US Fish and Wildlife Service, Gulf Coast Joint Venture, and the Gulf Coast

Prairies Landscape Conservation Cooperative. Anthropogenic changes, including loss and

degradation of coastal wetlands and adjacent prairies are likely responsible for historical

and recent declines in Mottled Duck populations. Rockefeller Wildlife Refuge (RWR)

supports research to help scientists and managers better understand Mottled Duck ecology

and population dynamics. Since 1994, Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries

1Rockefeller Wildlife Refuge, Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries, 5476 Grand Chenier

Hwy, Grand Chenier, LA 70643. *Corresponding author - jmarty@wlf.la.gov.

Manuscript Editor: Karl E. Miller

Notes of the Southeastern Naturalist, Issue 17/3, 2018

2018 Southeastern Naturalist Notes Vol. 17, No. 3

N52

J.R. Marty, S.A. Collins, and J.M. Whitaker

staff at RWR have banded over 40,000 Mottled Ducks, primarily in the coastal marshes

of southwestern Louisiana. Banding occurs during brood rearing and molt, primarily from

June–August (Baldassarre 2014). Birds are captured at night using spotlights and airboats.

Band-recovery data assists conservation planners in deriving estimates on annual survival

and harvest rates of Mottled Ducks. Banding efforts primarily occurred within the Louisiana

parishes of Cameron and Vermilion, including RWR, the southwestern Louisiana National

Wildlife Refuge Complex (Sabine and Cameron Prairie), and on private property north of

RWR. Herein, we report on 2 band-recovery records of Mottled Ducks banded in Cameron

Parish, LA, and recovered in Stutsman and Logan counties, ND.

On 30 September 2017, a waterfowl hunter harvested a Mottled Duck ~1 km north/

northeast of Medina, ND (Stutsman County; 46.934388°N, 99.294962°W; Fig. 1). The bird

decoyed into a harvested wheat field with ~15–20 A. platyrhynchos L. (Mallard) and appeared

to be in excellent health with no abnormalities when inspected in hand (K.J. Lines,

Minnesota Department of Natural Resources, St. Paul, MN, pers. comm.). The hunter

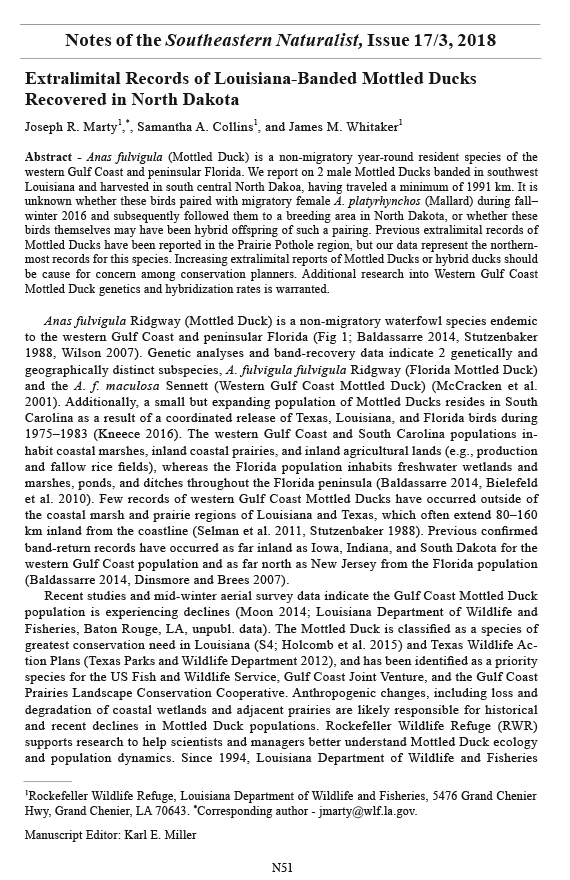

Figure 1. Approximate range of Anas fulvigula (Mottled Duck) along the Gulf of Mexico and peninsular

Florida (striped), Rockefeller Wildlife Refuge (black circle); previous extralimital Mottled Duck

recovery record near Alpena, SD (black cross; Selman et al. 2011); and the recovery locations of 2

male Mottled Ducks near Medina and Gackle, ND (black star).

N53

2018 Southeastern Naturalist Notes Vol. 17, No. 3

J.R. Marty, S.A. Collins, and J.M. Whitaker

reported the band (1697-16393) to the US Geological Survey Bird Banding Lab (USGS

BBL), which indicated the harvested bird was an adult male hatched in 2015 or earlier. The

banding location of the Mottled Duck on 09 August 2016 was Unit 3 of RWR, a 1584-ha

brackish marsh impoundment that is gravity-drained and controlled for estuarine management.

The primary management goals for Unit 3 consist of providing wintering waterfowl

habitat (e.g., water depths of 15–30 cm) and food resources through maintenance of intermediate/

brackish marsh communities and conditions favorable to submerged aquatic and

annual emergent vegetation. Typical vegetative communities on that site include annuals

such as Echniochloa walteri (Pursh) A. Heller (Walter’s millet), Leptochloa fusca (L.)

Kunth (Mangle Sprangletop), Eleocharis spp. (spikerush), and Cyperus spp. (flatsedge), as

well as aquatics such as Najas guadalupensis (Spreng.) Magnus (Southern Naiad), Ruppia

maritima L. (Widgeongrass), and Potamogeton pusillus L. (Small Pondweed).

On 26 October 2017, a waterfowl hunter harvested a Mottled Duck from a pothole in a

harvested bean field ~8 km south of Gackle, ND (Logan County). The bird decoyed with

~6 Mallards and appeared to be in excellent health when inspected in hand (K. Roberson

[hunter and harvester of the bird], Gackle, ND, pers. comm.). The hunter reported the band

(1697-16982) to the USGS BBL. The bird was an adult male hatched in 2012 or earlier.

The banding location of the Mottled Duck on 5 August 2013 was in the Big Burns Marsh,

~24 km northwest of RWR, a freshwater marsh dominated by Spartina patens (Aiton)

Muhl (Saltmeadow Cordgrass) and Panicum hemitomon Schult. (Maidencane) and drained

through the Mermentau River Basin.

The Mottled Ducks traveled a minimum straight-line distance of 1991 km (1237 mi)

between their banding locations in SW Louisiana and harvest locations in North Dakota.

Mixed flocks of Mallards and Mottled Ducks often are seen in coastal marshes of Louisiana

and Texas, and it is common for the 2 species to hybridize (Ford et al. 2017, McCracken et

al. 2001). Conceivably, these male Mottled Ducks may have paired with migratory female

Mallards during fall–winter 2016 and followed them to a breeding area in North Dakota.

Because photos and genetic analyses are not available, it is also possible that the 2 birds

harvested in North Dakota may have been hybrids, causing them to behave differently

than Mottled Ducks. Selman et al. (2011) reported a female Mottled Duck banded at RWR

harvested in South Dakota, which at the time represented the longest recorded movement

for the species (1680 km [1040 mi]). Selman et al. (2011) also noted a number of Mottled

Ducks reported in Wisconsin and North Dakota during the 1970s, but those records had not

been confirmed. Therefore, we believe our records from North Dakota are the northernmost

encounters for Mottled Ducks (311 km [193 mi] farther than that reported in Selman et al.

[2011]). Our findings support the hypothesis that extralimital repor ts of Mottled Ducks are

increasing in the Prairie Pothole Region (Dinsmore and Silock 2004, Selman et al. 2011).

Over the past century, natural and anthropogenic events (e.g., oil spills, hurricanes,

tropical storms, oil/gas exploration, agriculture) have forever altered the coastal prairie and

marsh ecosystems of Louisiana (Couvillion et al. 2011, Dahl 2011). Furthermore, climate

change and sea-level rise will continue to affect precipitation patterns, droughts, flushing

times, and salinity of coastal habitats (Ning et al. 2003). It is plausible that a reduction in

suitable habitat coupled with a declining population may make it more difficult for Mottled

Ducks to secure mates and increase the likelihood of hybridization. We concur with Ford et

al. (2017) and suggest that protecting and restoring coastal marsh habitat may help reduce

future hybridization rates. The Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority of Louisiana

has developed a Coastal Master Plan that outlines restoration measures to slow coastal erosion

(Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority of Louisiana 2012). These restoration

2018 Southeastern Naturalist Notes Vol. 17, No. 3

N54

J.R. Marty, S.A. Collins, and J.M. Whitaker

measures, although untested, may improve the long-term outlook for Mottled Duck habitat

in Louisiana. Because Mottled Ducks and Mallards both use freshwater marsh habitats

during the non-breeding period of the annual cycle, they likely have a long history of hybridization.

Recent research has indicated that hybridization rates may be as high as 9%

and 8% among the Florida and Western Gulf Coast Mottled Duck populations, respectively

(Ford et al. 2017, Williams et al. 2005). Increasing extralimital reports of Western Gulf

Coast Mottled Ducks or hybrid ducks (Mottled Duck x Mallard) should be cause for concern

among conservation planners. Continued research into Mottled Duck genetics and acceptable

hybridization rates is warranted.

Acknowledgments. We thank Tate Lines and Kyle Roberson for reporting the harvest of the banded

Mottled Ducks to the USGS BBL and for providing information pertaining to the harvest. We also

thank Willy Lines, Kevin Lines, Steve Merchant, Steve Cordts, and Larry Reynolds for notifying us,

and providing information on this record. We thank Ruth M. Elsey and 2 anonymous reviewers for

providing helpful comments that greatly improved this manuscript. Last, we greatly appreciate the effort

from all RWR staff who worked long hours and many nights to capture and band Mottled Ducks.

Literature Cited

Baldassarre, G.A. 2014. Mottled Duck. Pp. 436–459, In G.A. Baldassarre (Ed.). Ducks, Geese, and

Swans of North America. Vol.1. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, MD. 565 pp.

Bielefeld, R.R., M.G. Brasher, T.E. Moorman, and P.N. Gray. 2010. Mottled Duck (Anas fulvigula),

version 2.0. In A.F. Poole (Ed.). The Birds of North America. Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithica,

NY. Available online at https://doi.org/10.2173/bna.81. Accessed 30 April 2018.

Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority of Louisiana. 2012. Louisiana’s comprehensive master

plan for a sustainable coast. Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority of Louisiana, Baton

Rouge, LA.

Couvillion, B.R., J.A. Barras, G.D. Steyer, W. Sleavin, M. Fischer, H. Beck, N. Trahan, B. Griffin,

and D. Heckman. 2011. Land-area change in coastal Louisiana from 1932 to 2010: Pamphlet to

accompany Scientific Investigations Map 3164. US Geological Surv ey, Reston, VA.

Dahl, T.E. 2011. Status trends of wetlands in the conterminous United States 2004–2009. US Department

of the Interior, Fish and Wildlife Service, Washington, DC.

Dinsmore, S.J., and A. Brees. 2007. Mottled Duck at Saylorville Reservoir: First Iowa record. Iowa

Bird Life 77:32–34.

Dinsmore, S.J., and W.R. Silcock. 2004. Expansions. North American Birds 58:324–330.

Ford, J.F., W. Selman, and S.S. Taylor. 2017. Hybridization between Mottled Ducks (Anas fulvigula)

and Mallards (A. platyrhynchos) in the Western Gulf Coast Region. The Condor 119:683–696.

Holcomb, S.R., A.A. Bass, C.S. Reid, M.A. Seymour, N.F. Lorenz. B.B. Gregory, S.M. Javed, and

K.F. Balkum. 2015. Louisiana Wildlife Action Plan. Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries.

Baton Rouge, LA. 705 pp.

Kneece, M.R. 2016. Breeding and brood-rearing ecology of Mottled Ducks in the Ashepoo, Combahee,

and Edisto River Basin, South Carolina. Masters Thesis. Mississippi State University, Mississippi

State, MS. 135 pp.

McCracken, K.G., W.P. Johnson, and F.H. Sheldon. 2001. Molecular population genetics, phylogeography,

and conservation biology of the Mottled Duck (Anas fulvigula). Conservation Genetics

2:87–102.

Moon, J.A. 2014. Ecology of Mottled Ducks (Anas fulvigula) in the Texas Chenier

Plain Region. Ph.D

Dissertation. Stephen F. Austin State University, Nacogdoches, TX. 304 pp.

Ning, Z.H. R.E. Turner, T.E. Doyle, and K.K. Abdollahi. 2003. Preparing for a changing climate: The

potential consequences of climate variability and change: Gulf Coast Region. Gulf Coast Regional

Climate Change Impact Assessment, Baton Rouge, LA.

Selman, W., T.J. Hess, J. Linscombe, and L. Reynolds. 2011. An extralimital record of a Louisiana-

Banded Mottled Duck recovered in South Dakota. Southeastern Naturalist 10:570–574.

N55

2018 Southeastern Naturalist Notes Vol. 17, No. 3

J.R. Marty, S.A. Collins, and J.M. Whitaker

Stutzenbaker, C.D. 1988. The Mottled Duck: Its Life History, Ecology, and Management. Texas Parks

and Wildlife, Austin, TX. 209 pp.

Texas Parks and Wildlife Department. 2012. Texas Conservation action plan 2012–2016: Overview.

W. Connaly (Ed.). Austin, TX. 61 pp.

Williams, C.L., R.C. Brust, T.T. Fendley, G.R. Tiller Jr., and O.E. Rhodes Jr. 2005. A comparison of

hybridization between Mottled Ducks (Anas fulvigula) and Mallards (A. platyrhynchos) in Florida

and South Carolina using microsatellite DNA analysis. Conservation Genetics 6:445-453.

Wilson, B.C. 2007. North American Waterfowl Management Plan, Gulf Coast Joint Venture: Mottled

Duck conservation plan. North American Waterfowl Management Plan, Albuquerque, NM. 31 pp.

The Southeastern Naturalist is a peer-reviewed journal that covers all aspects of natural history within the southeastern United States. We welcome research articles, summary review papers, and observational notes.

The Southeastern Naturalist is a peer-reviewed journal that covers all aspects of natural history within the southeastern United States. We welcome research articles, summary review papers, and observational notes.