N1

2014 Southeastern Naturalist Notes Vol. 13, No. 1

A.J.J. Lehmicke and C.D. Jones

First Confirmed Records of Parasitism of Seaside Sparr ow Nests

by Brown-headed Cowbirds

Anna Joy J. Lehmicke1,* and Clark D. Jones1

Abstract - Molothrus ater (Brown-headed Cowbird) is a known nest parasite for numerous North

American passerines and has exacerbated the decline of many imperiled landbird species. However,

Brown-headed Cowbird habitat preferences do not frequently overlap with many salt marsh-dwelling

species. During intensive demographic research of Ammodramus maritimus (Seaside Sparrow) in

the coastal salt marshes of Mississippi (2010–2012), we documented the first instances of confirmed

nest parasitism of Seaside Sparrows by Brown-headed Cowbirds. We suggest that sea-level rise could

increase instances of nest parasitism in marsh-dwelling passerines by increasing the perimeter-to-area

ratio of marsh habitat and moving existing marsh in closer proximity to habitats preferred by Brownheaded

Cowbirds.

Ammodramus maritimus Wilson (Seaside Sparrow) is an obligate coastal marsh-dwelling

passerine that occurs in scattered populations from southern Maine to the northwestern

coast of the Gulf of Mexico in Texas (Post and Greenlaw 2009). Seaside Sparrows spend

their entire life cycle in coastal marshes, both breeding and wintering in the marsh. Little

is known about species-level population trends due to a lack of long-term and widespread

data, but a naturally limited total population due to restricted range (estimated at slightly

more than 100,000 individuals; National Audubon Society 2007) and threats to coastal wetland

habitat raise concerns for their future conservation status. They are on the Audubon

WatchList of species in need of conservation action due to their highly specialized habitat

needs and continuing habitat loss (National Audubon Society 2007). In addition, Seaside

Sparrows are categorized as a species of conservation concern throughout their range by the

US Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS 2008) and are considered a Tier I species by the US

Partners in Flight (Rosenberg 2004).

Molothrus ater Boddaert (Brown-headed Cowbird) is an obligate brood parasite found

throughout the contiguous United States. While the species was initially restricted to

short-grass plains, human modification of habitat has allowed for significant range expansion

(Lowther 1993). Habitat fragmentation has also brought Brown-headed Cowbirds

into contact with many bird species previously protected from parasitism, particularly interior

forest species. Brown-headed Cowbird parasitism has been implicated in the decline

of many species, including the federally endangered Setophaga kirtlandii Baird (Kirtland’s

Warbler; Mayfield 1961) and Vireo atricapilla Woodhouse (Black-capped Vireo;

USFWS 1991).

While Brown-headed Cowbirds are found throughout the United States, they are not

found in all habitat types. Brown-headed Cowbirds are typically found in habitats with a

high perimeter-to-area ratio rather than open areas (Jensen and Cully 2005) or forest interior

(>350 m from the forest edge; Howell et al. 2007). Studies in recent years have found low

to no brood parasitism of coastal marsh-nesting passerines (Greenberg et al. 2006, Reinert

2006), suggesting this habitat is not preferred by Brown-headed Cowbirds, perhaps due to

absence of suitable perch sites. Here we document the first instances of widespread nest

1Warnell School of Forestry and Natural Resources, University of Georgia, Athens, GA 30602.

*Corresponding author - lehmicke@uga.edu.

Manuscript Editor: Roger W. Perry

Notes of the Southeastern Naturalist, Issue 13/1, 2014

2014 Southeastern Naturalist Notes Vol. 13, No. 1

N2

A.J.J. Lehmicke and C.D. Jones

parasitism of Seaside Sparrows by Brown-headed Cowbirds and suggest that increasing sea

levels may lead to higher levels of nest parasitism of tidal marsh-nesting passerine species.

Field-Site Description. We conducted fieldwork in two marshes in Jackson County, MS,

on the Mississippi Gulf Coast. Grand Bay National Estuarine Research Reserve (GBNERR;

30º19'N, 88º27'W) is composed of approximately 7400 ha of wetlands, pine savannas, and

terrestrial habitats. The tidal marsh areas are predominately polyhaline (salinity = 18−35

ppt; Cowardin et al. 1979) and are dominated by Juncus roemerianus Scheele (Needlegrass

Rush), interspersed with narrow bands of Spartina alterniflora Loisel (Atlantic Cordgrass).

The Pascagoula River Marsh Coastal Preserve (30º23'N, 88º34'W) is a 4600-ha site of

mostly oligohaline and mesohaline (0.5−5 ppt and 5−18 ppt; Cowardin et al. 1979) marsh,

dominated by J. roemerianus, S. alterniflora, and Spartina cynosuroides L. (Big Cordgrass).

Methods. During three breeding seasons (2010–2012), we conducted intensive demographic

work on seven plots (three at GBNERR, four on the Pascagoula River), averaging

about 4 ha each. Our primary research focus required finding and monitoring Seaside

Sparrow nests. We found nests during all nesting stages (building, laying, incubating, and

nestling) and checked them every two to four days until the nest failed or nestlings fledged.

We carefully noted nest contents during each check, although we attempted to minimize the

time spent at the nest in order to cause as little disturbance as possible.

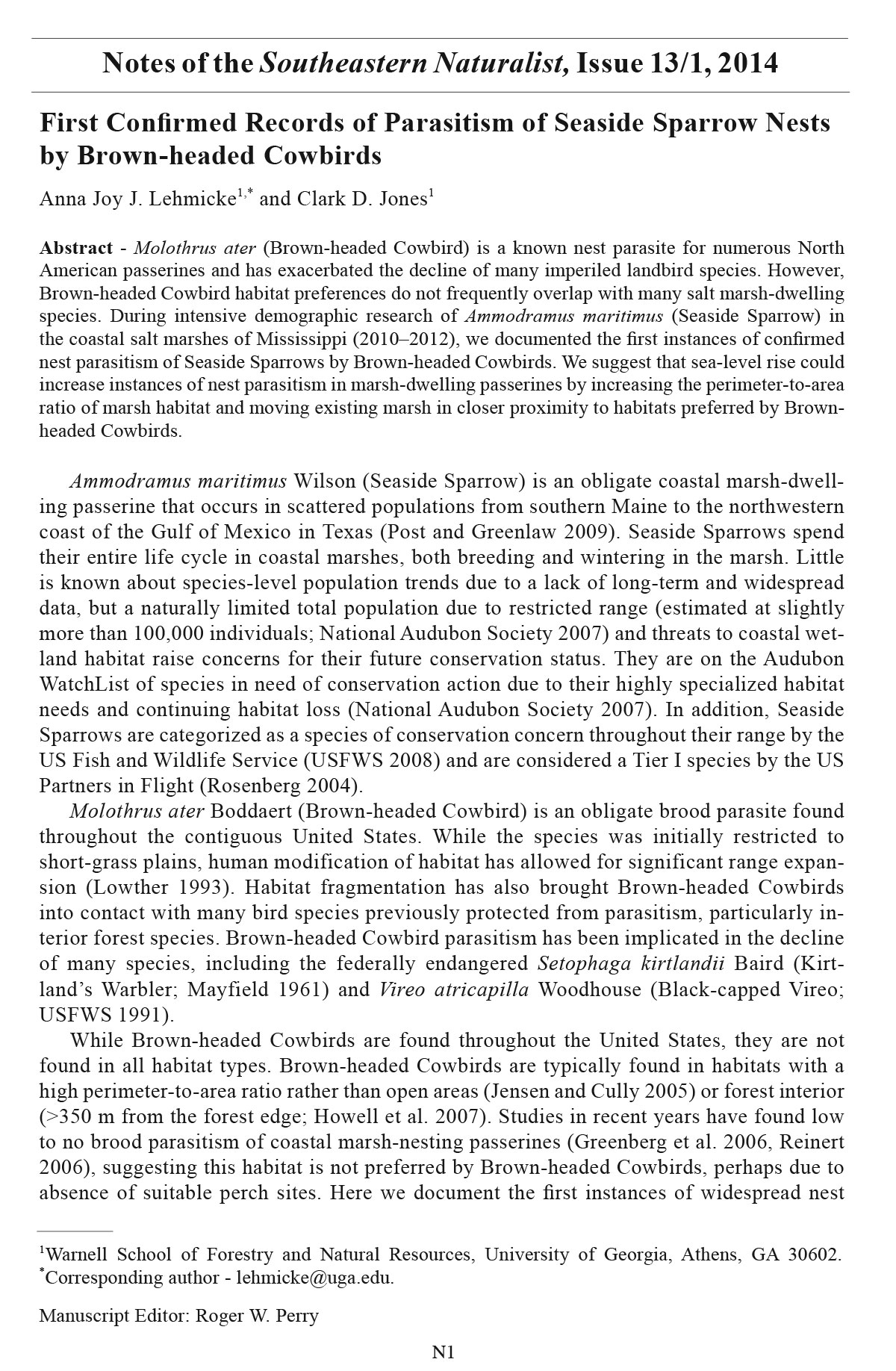

Results. During three seasons of intense demographic work (2010−2012), we found five

Seaside Sparrow nests containing one Brown-headed Cowbird nestling each: four at the

Grand Bay National Estuarine Research Reserve and one in the Pascagoula River Marsh

Coastal Preserve. Of the five parasitized nests, one had only a Brown-headed Cowbird; at

least one Seaside Sparrow nestling was present in the remaining four (Fig. 1). The nestlings

in three of the five nests fledged, although we only observed an adult Seaside Sparrow feeding

a Brown-headed Cowbird fledgling from one of the three. Seaside Sparrow fledglings

are difficult to relocate and it was not unusual for us to never observe adults with fledglings,

even when we were confident that the nestlings fledged. Therefore, we are hesitant

to speculate on potential survival of Brown-headed Cowbird fledglings or Seaside Sparrow

fledglings from parasitized nests.

As part of our Seaside Sparrow demographic work, we monitored seven plots, but all

five of the parasitized nests were found on two of those plots. One of the two plots had

a high concentration of tall (>2 m) shrubs, providing ample perch sites for adult Brownheaded

Cowbirds. The second site had no shrubs, was comprised primarily of low-growing

S. alterniflora and Distichlis spicata L. (Inland Saltgrass), and was far from upland habitat

(≈3 km); however, on multiple occasions we observed both male and female adult Brownheaded

Cowbirds perched on PVC pipes used as survey markers.

It is likely that more than five nests were parasitized during the three summers. Brownheaded

Cowbird and Seaside Sparrow eggs are nearly indistinguishable without close

inspection (i.e., they are easily overlooked when trying to minimize disturbance to wellconcealed

nests), so a cowbird egg may have gone unnoticed in nests that failed before

hatching. Indeed, two of the five parasitized nests were found during incubation and the

presence of a cowbird was not recognized until the eggs hatched. At the two sites where

Brown-headed Cowbird nestlings were observed, we found 158 Seaside Sparrow nests over

the three breeding seasons. If we extrapolate from the proportion of hatched nests containing

a Brown-headed Cowbird nestling (5/84 or 5.95%), then potentially four out of the 74

nests that did not hatch at those sites contained a Brown-headed Cowbird egg. We do not

believe that we missed any Brown-headed Cowbird nestlings that were present, because

while Brown-headed Cowbirds and Seaside Sparrows are similar in size and mass on hatch

N3

2014 Southeastern Naturalist Notes Vol. 13, No. 1

A.J.J. Lehmicke and C.D. Jones

day and one day after hatching (cowbirds: 2.6 and 4.6 g [Scott 1979], sparrows: 2.4 and 3.8

g [Post and Greenlaw 2009]), Brown-headed Cowbirds can be distinguished upon hatching

as they are covered with white/light gray down compared to the Seaside Sparrows’ dark

gray down (Fig. 1).

Discussion. These observations are significant because they are the first records of

a Seaside Sparrow population with widespread parasitism by Brown-headed Cowbirds

and the first indisputable records of Seaside Sparrows successfully rearing and fledging

cowbirds. To our knowledge, the only previously published observation of a Seaside

Sparrow and Brown-headed Cowbird interaction involved adult Seaside Sparrows feeding a

fledgling Brown-headed Cowbird (Bagg and Eliot 1937). That account is generally accepted

as evidence that Seaside Sparrows can successfully raise Brown-headed Cowbirds, and the

sparrows are listed as hosts based on this observation (Friedmann 1963). However, Klein

and Rosenberg (1986) pointed out that classifying any species as a Brown-headed Cowbird

host based solely on the observation of an adult of the host species feeding a Brown-headed

Figure 1. Seaside Sparrow Ammodramus maritimus nestling (left) and Brown-headed Cowbird

Molothrus ater nestling (right), four days post-hatch.

2014 Southeastern Naturalist Notes Vol. 13, No. 1

N4

A.J.J. Lehmicke and C.D. Jones

Cowbird fledgling is problematic. There are numerous accounts of multiple species of adult

birds feeding the same fledgling Brown-headed Cowbird, clearly showing that fledgling

Brown-headed Cowbirds are sometimes fed by non-host adults (Klein and Rosenberg 1986,

Scott 1988). Additionally, Post and Greenlaw (2009) agree that this single observation in

itself is not proof that the same Seaside Sparrows incubated and fledged the Brown-headed

Cowbird, as Seaside Sparrows have been observed feeding both Agelaius phoeniceus L.

(Red-winged Blackbird; Rakestraw and Baker 1981) and Ammodramus caudacutus Gmelin

(Saltmarsh Sparrow; Post and Greenlaw 2009) fledglings.

A second, unpublished observation involved a likely Brown-headed Cowbird egg in

a probable Seaside Sparrow nest in Connecticut (C. Elphick, University of Connecticut,

Storrs, CT, pers. comm.). While the female was never observed well enough to definitively

say that it was a Seaside Sparrow nest, the nest structure and the general impression of the

flushing female suggest that it was a Seaside Sparrow rather than a Saltmarsh Sparrow. The

egg was noticeably larger and the spotting pattern and background coloration were distinct.

Notably, this egg was the only evidence of cowbird parasitism out of over 1100 Saltmarsh

Sparrow nests and 100 Seaside Sparrow nests observed during the study, suggesting that

there may be differences in susceptibility to parasitism among populations. Even with these

two records, our observations still provide the first undeniable evidence that Seaside Sparrows

can successfully incubate, raise, and fledge Brown-headed Cowbirds and that there are

populations where such parasitism is a regular occurrence.

While Brown-headed Cowbirds do not seem to be a current threat to Seaside Sparrow

populations, there is real potential this could change in the near future. Brown-headed Cowbirds

are edge specialists and rising sea levels will likely push salt marshes farther inland

or force Seaside Sparrows to nest closer to the upland edge of marshes. These changes will

potentially increase the risk of cowbird parasitism of Seaside Sparrow nests, especially

since Seaside Sparrows are “good” hosts, meaning that they can successfully fledge cowbird

young. Additionally, if Seaside Sparrow habitat retreats farther inland, other predation pressures

will likely increase. In fact, surveys conducted over three breeding seasons indicate

that abundance of Seaside Sparrows in our study area is lower at sites with a higher proportion

of upland habitat, possibly due to proximity of predator source populations (A.J.J.

Lehmicke, unpubl. data). These increased predation pressures will likely be exacerbated

by brood parasitism. Recognizing Brown-headed Cowbirds as a potential threat to marshnesting

passerines, at least along the northern coast of the Gulf of Mexico, can allow for

monitoring and management before they become a population-level problem.

Acknowledgments. Our fieldwork was supported by grants from the Georgia Ornithological

Society and the United States Fish and Wildlife Service through the Gulf Coast Joint

Venture. We thank M. Woodrey and R. Cooper for guidance on this project, and our field

assistants L. Duval, J. Jetchev, K. Morris, A. Densborn, and C. Randall.

Literature Cited

Bagg, A.C., and S.A. Eliot, Jr. 1937. Birds of the Connecticut Valley in Massachusetts. Hampshire

Bookshop, Northampton, MA.

Cowardin, L.M., V. Carter, F.C. Golet, and E.T. LaRoe. 1979. Classification of wetlands and deepwater

habitats of the United States. US Department of the Interior, Fish and Wildlife Service,

Washington, DC.

Friedmann, H. 1963. Host relations of the parasitic cowbird. US Natural Museum Bulletin 233:1−276.

Greenberg, R., C. Elphick, J.C. Nordby, C. Gjerdrum, H. Spautz, W.G. Shriver, B. Schmeling, B.

Olsen, P. Marra, N. Nur, and M. Winter. 2006. Flooding and predation: Trade-offs in the nesting

ecology of tidal-marsh sparrows. Studies in Avian Biology 32:96−109.

N5

2014 Southeastern Naturalist Notes Vol. 13, No. 1

A.J.J. Lehmicke and C.D. Jones

Howell, C.A., W.D. Dijak, and F.R. Thompson III. 2007. Landscape context and selection for forest

edge by breeding Brown-headed Cowbirds. Landscape Ecology 22:27 3−284.

Jensen, W.E., and J.F. Cully, Jr. 2005. Density-dependent habitat selection by Brown-headed Cowbirds

(Molothrus ater) in tallgrass prairie. Oecologia 142:136−149.

Klein, N.K., and K.V. Rosenberg. 1986. Feeding of Brown-headed Cowbird (Molothrus ater) fledglings

by more than one “host” species. The Auk 103:213−214.

Lowther, P.E. 1993. Brown-headed Cowbird (Molothrus ater). No. 47, In A. Poole (Ed.). The Birds

of North America Online. Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY. Available online at http://bna.

birds.cornell.edu.proxy-remote.galib.uga.edu/bna/species/047. Accessed 5 December 2012.

Mayfield, H. 1961. Cowbird parasitism and the population of the Kirtland’s Warbler. Evolution

15(2):174−179.

National Audubon Society. 2007. Audubon WatchList 2007. Available online at http://birds.audubon.

org/2007-audubon-watchlist. Accessed 10 September 2010.

Post, W., and J.S. Greenlaw. 2009. Seaside Sparrow (Ammodramus maritimus). No. 127, In A. Poole

(Ed.) The Birds of North America Online. Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY. Available

online at http://bna.birds.cornell.edu.proxy-remote.galib.uga.edu/bna/species/127. Accessed 5

December 2012.

Rakestraw, J.L., and J.L. Baker. 1981. Dusky Seaside Sparrow feeds Red-winged Blackbird fledglings.

Wilson Bulletin 93:540.

Reinert, S.F. 2006. Avian nesting response to tidal-marsh flooding: Literature review and a case for

adaptation in the Red-winged Blackbird. Studies in Avian Biology 32:77−95.

Rosenberg, K.V. 2004. Partners in Flight continental priorities and objectives defined at the state and

bird conservation region levels: Mississippi. Available online at http://fishwildlife.org/pdfs/Birds/

MS_PIF_OBJ_PRIO.doc. Accessed 10 September 2010.

Scott, D.M. 1988. House Sparrow and Chipping Sparrow feed the same fledgling Brown-headed

Cowbird. Wilson Bulletin 100:323−324.

Scott, T.W. 1979. Growth and age determination of nestling Brown-headed Cowbirds. Wilson Bulletin

91:464−466.

US Fish and Wildlife Service (UFSWS). 1991. Black-capped Vireo recovery plan. Office of Endangered

Species, Albuquerque, NM.

USFWS. 2008. Birds of conservation concern 2008. Division of Migratory Bird Management,

Arlington, Virginia. Available online at http://www.fws.gov/migratorybirds/. Accessed 10 September

2010.

The Southeastern Naturalist is a peer-reviewed journal that covers all aspects of natural history within the southeastern United States. We welcome research articles, summary review papers, and observational notes.

The Southeastern Naturalist is a peer-reviewed journal that covers all aspects of natural history within the southeastern United States. We welcome research articles, summary review papers, and observational notes.